Ljubljanski zvon (The Ljubljana Bell) was a journal published in Ljubljana in Slovene between 1881 and 1941. It was considered one of the most prestigious literary and cultural magazines in Slovenia.

Ljubljanski zvon (The Ljubljana Bell) was a journal published in Ljubljana in Slovene between 1881 and 1941. It was considered one of the most prestigious literary and cultural magazines in Slovenia.

The journal was founded in 1881 [1] as a gazette of the circle of young Slovene liberals, mostly from Carniola, who were dissatisfied with the editorial policy of the magazine Zvon (The Bell), published in Vienna by the doyen of the Young Slovenes movement, Josip Stritar. The group, centered around the authors, journalists and political activists Josip Jurčič, Janko Kersnik, Ivan Tavčar, and Fran Levec, regarded Stritar's editorial policy as too detached from the reality in the Slovene Lands. They also rejected Stritar's post-romantic aesthetic views, which they saw as backward and too influenced by Schopenhauer's pessimism. Instead, they turned to realism and later to naturalism.

Soon after its establishment, Ljubljanski zvon became the most prestigious literary magazine in Slovene. From the turn of the 20th century onward, it became also a platform for political and public debates. Since its formation, it supported liberal and progressive views. In 1888, conservative Roman Catholic intellectuals founded the magazine Dom in svet to counter the influence of Ljubljanski zvon. From then on, the competition between the two journals became one of the characteristic of the Slovene cultural and public life.

During the centralist regime of King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, the editorial board of the journal suffered a decisive split between a minority who supported the project of creating a unitary Yugoslav nation, and a majority of those who clang to the specific national and cultural identity of the Slovene people. The first serious conflict broke out in 1931, when the chief editor Fran Albreht decided to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the magazine by adding a new subtitle: Slovenska revija (Slovene magazine). The decision was made in period when the Yugoslav authorities were sponsoring the official use of Serbo-Croatian in the Drava Banovina and when even the name "Slovenia" was banned from official public use.

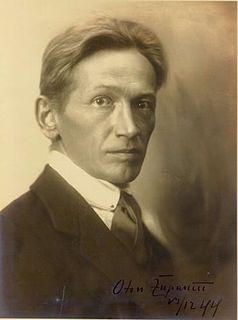

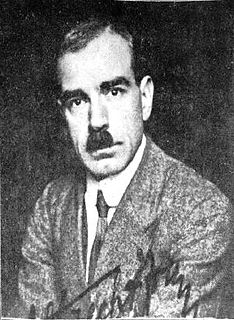

The following year, a polemics broke out between the poet Oton Župančič and the literary critic Josip Vidmar on the issue of Slovene identity. Župančič published an essay on the occasion of the visit of the Slovene-born American writer Louis Adamic in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, in which he maintained that the Slovenes shouldn't be too preoccupied about their language, since they can keep their identity even if they lose the language. The article was perceived by many as a subtle support of the cultural policies of the centralist monarchist regime. When the literary critic Josip Vidmar wanted to publish his negative review of Župančič's article in the journal, he was prevented of doing so by the publisher, closely linked to the National-Liberal political establishment which supported King Alexander's dictatorship. In protest, most of the editorial board stepped down, including the chief editor Fran Albreht. In the same year, Albreht published a book entitled Kriza Ljubljanskega Zvona (The Crisis of The Ljubljana Bell), in which he made public all the details of the controversy. The book greatly damaged the reputation of the magazine. In 1933, the younger generations of Slovene liberal intellectuals that rejected Yugoslav nation building founded a new journal, called Sodobnost , with Albreht as editor.

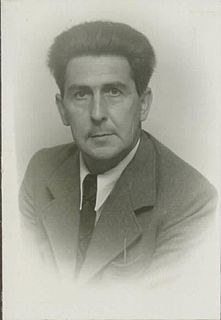

The split of 1932-33 ruined the reputation of the magazine. Many of the most talented writers went to Sodobnost and the Ljubljanski zvon lost a substantial number of subscribers. In 1935, the writer and journalist Juš Kozak was chosen as the new editor. He opened the journal to Marxist and Communist authors, which published their articles under pseudonyms (among them was also the young Dušan Pirjevec, who later became one of the foremost Marxist intellectuals in Slovenia). After the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the journal was closed down [1] by the Italian occupation authorities of the Province of Ljubljana. After the end of World War II in 1945, the new Communist authorities did not allow the re-establishment of the journal, despite the pro-Marxist inclination of its last editorial board.

The editors of Ljubljanski zvon included figures such as Fran Levec, Anton Funtek, Janko Kersnik, Anton Aškerc, Oton Župančič, Anton Melik, Fran Albreht, Anton Ocvirk, Tone Seliškar and Juš Kozak. Many of the most important Slovene authors of the period published their works in the journal, including Dragotin Kette, Josip Murn, Ivan Cankar and Alojz Gradnik. The journal published also articles in the field of humanities and social sciences, both from Slovene and non-Slovene authors.

All issues of the journal can be freely accessed online on the Digital Library of Slovenia.

Igo Gruden was a Slovene poet and translator.

Ivan Cankar was a Slovene writer, playwright, essayist, poet, and political activist. Together with Oton Župančič, Dragotin Kette, and Josip Murn, he is considered as the beginner of modernism in Slovene literature. He is regarded as the greatest writer in Slovene, and has sometimes been compared to Franz Kafka and James Joyce.

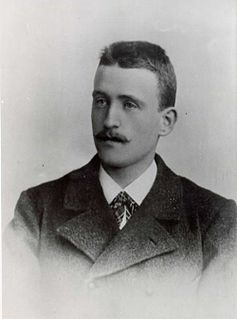

Anton Aškerc was an Slovenian poet and Roman Catholic priest who worked in Austria, best known for his epic poems.

Fran Levstik was a Slovene writer, political activist, playwright and critic. He was one of the most prominent exponents of the Young Slovene political movement.

Josip Murn, also known under the pseudonym Aleksandrov was a Slovene symbolist poet. Together with Ivan Cankar, Oton Župančič, and Dragotin Kette, he was regarded as one of the beginners of modernism in Slovene literature. After France Prešeren and Edvard Kocbek, Murn was probably the most influential Slovene poet of the last two centuries.

Oton Župančič was a Slovene poet, translator, and playwright. He is regarded, alongside Ivan Cankar, Dragotin Kette and Josip Murn, as the beginner of modernism in Slovene literature. In the period following World War I, Župančič was frequently regarded as the greatest Slovenian poet after Prešeren, but in the last forty years his influence has been declining and his poetry has lost much of its initial appeal.

Fran Albreht was a Slovenian poet, editor, politician and partisan. He also published under the pseudonym Rusmir.

Ivan Tavčar was a Slovenian writer, lawyer, and politician.

The Slovene Society is the second-oldest publishing house in Slovenia, founded on February 4, 1864 as an institution for the scholarly and cultural progress of Slovenes.

Dušan Pirjevec, known by his nom de guerre Ahac, was a Slovenian Partisan, literary historian and philosopher. He was one of the most influential public intellectuals in post–World War II Slovenia.

Sodobnost is a Slovenian literary and cultural magazine, established in 1933. It is considered the oldest of currently existing literary magazines in Slovenia. Although Sodobnost has traditionally been a magazine focused on cultural and literary issues, it nowadays covers a wide range of current affairs. It is part of the Eurozine editorial project.

Dom in svet was a Catholic cultural and literary journal published in Slovenia.

Ferdo Kozak was a Slovenian author, playwright, editor and politician.

Primož Kozak was a Slovenian playwright and essayist. Together with Dominik Smole, Dane Zajc and Taras Kermauner, he was the most visible representative of the so-called Critical generation, a group of Slovenian authors and intellectuals that reflected on the paradoxes of the communist regime, and the relation between power and individual existence in general.

Young Slovenes were a Slovene national liberal political movement in the 1860s and 1870s, inspired and named after the Young Czechs in Bohemia and Moravia. They were opposed to the national conservative Old Slovenes. They entered in a crisis in the 1880s, and disappeared from political life by the 1890s. They are considered the precursors of Liberalism in Slovenia.

Prežihov Voranc was the pen name of Lovro Kuhar, a Slovene writer and communist political activist. Voranc's literary reputation was established during the 1930s with a series of Slovene novels and short stories in the social realist style, notable for their depictions of poverty in rural and industrial areas of Slovenia. His most important novels are Požganica (1939) and Doberdob (1940).

Janko Kersnik was a Slovene writer and politician. Together with Josip Jurčič, he is considered the most important representative of literary realism in Slovene.