Related Research Articles

Dorothy Louise Taliaferro "Del" Martin and Phyllis Ann Lyon were an American lesbian couple based in San Francisco who were known as feminist and gay-rights activists.

A domestic partnership is an intimate relationship between people, usually couples, who live together and share a common domestic life but who are not married. People in domestic partnerships receive legal benefits that guarantee right of survivorship, hospital visitation, and other rights.

A California domestic partnership is a legal relationship, analogous to marriage, created in 1999 to extend the rights and benefits of marriage to same-sex couples. It was extended to all opposite-sex couples as of January 1, 2016 and by January 1, 2020 to include new votes that updated SB-30 with more benefits and rights to California couples choosing domestic partnership before their wedding. California Governor Newsom signed into law on July 30, 2019.

In the United States, domestic partnership is a city-, county-, state-, or employer-recognized status that may be available to same-sex couples and, sometimes, opposite-sex couples. Although similar to marriage, a domestic partnership does not confer any of the myriad rights and responsibilities of marriage afforded to married couples by the federal government. Domestic partnerships in the United States are determined by each state or local jurisdiction, so there is no nationwide consistency on the rights, responsibilities, and benefits accorded domestic partners.

Pride at Work (P@W) is an American lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender group (LGBTQ+) of labor union activists affiliated with the AFL-CIO.

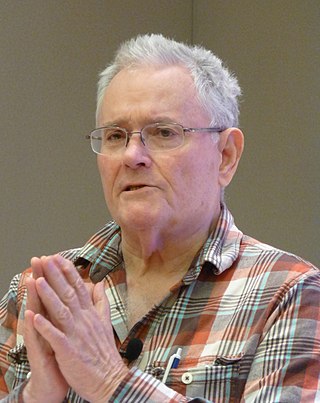

Tom Brougham is a Berkeley, California gay rights activist who was the first to suggest a new legal category for recognizing couples other than marriage, and who coined the phrase domestic partnership.

Harry Britt was an American politician and gay rights activist. Born in Texas, he worked as a Methodist pastor in Chicago as a young man and later moved to San Francisco. There, he worked with Harvey Milk until Milk's assassination in 1978. He was appointed to his seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, where he remained until 1993, and served as the board's president from 1989 to 1990. Britt was a Democrat and member of the Democratic Socialists of America. He ran for the United States House of Representatives in 1987 and for the California State Assembly in 2002, but was unsuccessful both times.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2008.

Same-sex unions in the United States are available in various forms in all states and territories, except American Samoa. All states have legal same-sex marriage, while others have the options of civil unions, domestic partnerships, or reciprocal beneficiary relationships. The federal government only recognizes marriage and no other legal union for same-sex couples.

Same-sex marriage has been recognized in Montana since a federal district court ruled the state's ban on same-sex marriage unconstitutional on November 19, 2014. Montana had previously denied marriage rights to same-sex couples by statute since 1997 and in its State Constitution since 2004. The state appealed the ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, but before that court could hear the case, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all same-sex marriage bans in the country in Obergefell v. Hodges, mooting any remaining appeals.

As of 2015, all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia legally recognize and document same-sex relationships in some fashion, be it by same-sex marriage, civil union or domestic partnerships. Many counties and municipalities outside of these states also provide domestic partnership registries or civil unions which are not officially recognized by the laws of their states, are only valid and applicable within those counties, and are usually largely unaffected by state law regarding relationship recognition. In addition, many cities and counties continue to provide their own domestic partnership registries while their states also provide larger registries ; a couple can only maintain registration on one registry, requiring the couple to de-register from the state registry before registering with the county registry.

Before the legalization of same-sex marriage in Florida in January 2015, same-sex couples were able to have their relationships recognized in some Florida localities that had established a legal status known as domestic partnership.

Several jurisdictions in the U.S. state of Ohio have established domestic partnerships for same-sex couples. The fate of these partnerships remains uncertain since marriage has become available to all couples.

The history of LGBT residents in California, which includes centuries prior to the 20th, has become increasingly visible recently with the successes of the LGBT rights movement. In spite of the strong development of early LGBT villages in the state, pro-LGBT activists in California have campaigned against nearly 170 years of especially harsh prosecutions and punishments toward gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Georgia enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. LGBTQ rights in the state have been a recent occurrence, with most improvements occurring from the 2010s onward. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1998, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy law. Same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since 2015, in accordance with Obergefell v. Hodges. In addition, the state's largest city Atlanta, has a vibrant LGBTQ community and holds the biggest Pride parade in the Southeast. The state's hate crime laws, effective since June 26, 2020, explicitly include sexual orientation.

This is a list of events in 2011 that affected LGBT rights.

California is seen as one of the most liberal states in the U.S. in regard to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights, which have received nationwide recognition since the 1970s. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in the state since 1976. Discrimination protections regarding sexual orientation and gender identity or expression were adopted statewide in 2003. Transgender people are also permitted to change their legal gender on official documents without any medical interventions, and mental health providers are prohibited from engaging in conversion therapy on minors.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Wisconsin enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. However, the transgender community may face some legal issues not experienced by cisgender residents, due in part to discrimination based on gender identity not being included in Wisconsin's anti-discrimination laws, nor is it covered in the state's hate crime law. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Wisconsin since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Wolf v. Walker. Discrimination based on sexual orientation is banned statewide in Wisconsin, and sexual orientation is a protected class in the state's hate crime laws. It approved such protections in 1982, making it the first state in the United States to do so.

The U.S. state of Texas issues marriage licenses to same-sex couples and recognizes those marriages when performed out-of-state. On June 26, 2015, the United States legalized same-sex marriage nationwide due to the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. Prior to the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling Article 1, Section 32, of the Texas Constitution provided that "Marriage in this state shall consist only of the union of one man and one woman," and "This state or a political subdivision of this state may not create or recognize any legal status identical or similar to marriage." This amendment and all related statutes have been ruled unconstitutional and unenforceable. Some cities and counties in the state recognize both same-sex and opposite-sex domestic partnerships.

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community in the United States.

References

- ↑ "A Brief History of Domestic Partnerships" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-16. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ "Two Year Report on the San Francisco Equal Rights Ordinance" (PDF). Sfgov.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ Joe Garofoli (2012-12-12). "Ethel Manheimer, Berkeley activist, dies". SFGate. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ Bishop, Katherine (1989-05-31). "San Francisco Grants Recognition To Couples Who Aren't Married". New York Times.

- ↑ Bailey, Robert (1998). Gay Politics, Urban Politics . New York: Columbia University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-231-09663-8.

- ↑ Reinhold, Robert (1990-10-30). "Campaign Trail; 2 Candidates Who Beat Death Itself". New York Times.

- ↑ "Filing a Domestic Partnership Agreement". San Francisco Office of the City Clerk. Archived from the original on 2008-11-14. Retrieved 2008-11-19.