Related Research Articles

Arianism is a Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God. It is named after its major proponent, Arius. It is considered heretical by most modern mainstream branches of Christianity. It is held by a minority of modern denominations, although some of these denominations hold related doctrines such as Socinianism, and some shy away from use of the term Arian due to the term's historically negative connotations. Modern mainstream denominations sometimes connected to the teaching include Jehovah's Witnesses, some individual churches within the Churches of Christ, as well as some Hebrew Roots Christians and Messianic Jews.

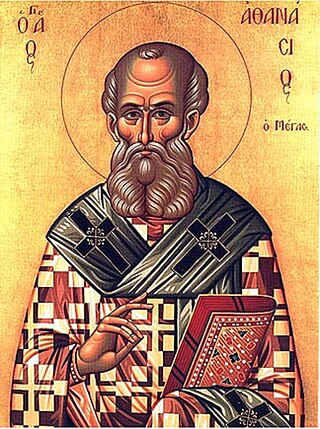

Athanasius I of Alexandria, also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Christian theologian and the 20th pope of Alexandria. His intermittent episcopacy spanned 45 years, of which over 17 encompassed five exiles, when he was replaced on the order of four different Roman emperors. Athanasius was a Church Father, the chief proponent of Trinitarianism against Arianism, and a noted Egyptian Christian leader of the fourth century.

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

Arius was a Cyrenaic presbyter and ascetic. He has been regarded as the founder of Arianism, which holds that Jesus Christ was not coeternal with God the Father, but was rather created before time. Arian theology and its doctrine regarding the nature of the Godhead showed a belief in subordinationism, a view notably disputed by 4th century figures such as Athanasius of Alexandria.

Eustathius of Antioch, sometimes surnamed the Great, was a Christian bishop and archbishop of Antioch in the 4th century. His feast day in the Eastern Orthodox Church is February 21.

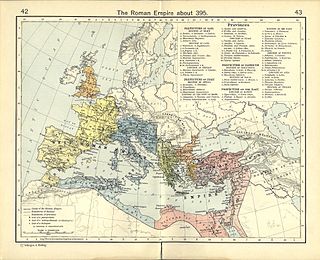

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous province of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyrians and Celts, it was conquered by the Romans in the 1st century BC and subsequently became the capital of the Roman province of Pannonia Inferior. In 293 AD, Sirmium was proclaimed one of the four capitals of the Roman Empire. It was also the capital of the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum and of Pannonia Secunda. The site is protected as an archaeological Site of Exceptional Importance. The modern region of Syrmia was named after the city.

Hosius of Corduba, also known as Hosius the Confessor, Osius or Ossius, was a bishop of Corduba and an important and prominent advocate for Homoousion Christianity in the Arian controversy that divided the early Christianity.

The Acacians, or perhaps better described as the Homoians or Homoeans, were a non-Nicene branch of Christianity that dominated the church during much of the fourth-century Arian Controversy. They declared that the Son was similar to God the Father, without reference to substance (essence). Homoians played a major role in the Christianization of the Goths in the Danubian provinces of the Roman Empire.

The Councils of Sirmium were the five episcopal councils held in Sirmium in 347, 351, 357, 358 and finally in 375 or 378. The third—the most important of the councils—marked a temporary compromise between Arianism and the Western bishops of the Christian church. At least two of the other councils also dealt primarily with the Arian controversy. All of these councils were held under the rule of Constantius II, who was sympathetic to the Arians.

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are co-eternal, and of the same substance, or consubstantial, and was therefore considered to be heretical by many contemporary Christians.

Marcellus of Ancyra was a Bishop of Ancyra and one of the bishops present at the Council of Ancyra and the First Council of Nicaea. He was a strong opponent of Arianism, but was accused of adopting the opposite extreme of modified Sabellianism. He was condemned by a council of his enemies and expelled from his see, though he was able to return there to live quietly with a small congregation in the last years of his life. He is also said to have destroyed the temple of Zeus Belos at Apamea.

Hypostasis, from the Greek ὑπόστασις (hypóstasis), is the underlying, fundamental state or substance that supports all of reality. It is not the same as the concept of a substance. In Neoplatonism, the hypostasis of the soul, the intellect (nous) and "the one" was addressed by Plotinus. In Christian theology, the Holy Trinity consists of three hypostases: that of the Father, that of the Son, and that of the Holy Spirit.

Auxentius of Milan or of Cappadocia, was an Arian theologian and bishop of Milan. Because of his Arian faith, Auxentius is considered by the Catholic Church as an intruder and he is not included in the Catholic lists of the bishops of Milan such as that engraved in the Cathedral of Milan.

Homoiousios is a Christian theological term, coined in the 4th century to identify a distinct group of Christian theologians who held the belief that God the Son was of a similar, but not identical, essence with God the Father.

Photinus was a Christian bishop of Sirmium in Pannonia Secunda, best known for denying the incarnation of Christ, thus being considered a heresiarch by both the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. His name became synonymous in later literature for someone asserting that Christ was not God. His teachings are mentioned by various ancient authors, like Ambrosiaster (Pseudo-Ambrose), Hilary of Poitiers, Socrates Scholasticus, Sozomen, Ambrose of Milan, Augustine of Hippo, John Cassian, Sulpicius Severus, Jerome, Vigilius of Thapsus and many others.

The Council of Serdica, or Synod of Serdica, was a synod convened in 343 at Serdica in the civil diocese of Dacia, by Emperors Constans I, Augustus in the West, and Constantius II, Augustus in the East. It attempted to resolve "the tension between East and West in the Church." “The council was a disaster: the two sides, one from the west and the other from the east, never met as one.”

Stridon was a town in the Roman province of Dalmatia, of unknown location, best known as the birthplace of Saint Jerome. In 379, the town was destroyed by the Goths. Jerome wrote about it in his work De viris illustribus: "Jerome was born to his father Eusebius, [in the] town of Strido, which the Goths overthrew, and was once at the border between Dalmatia and Pannonia.".

The Arian controversy was a series of Christian disputes about the nature of Christ that began with a dispute between Arius and Athanasius of Alexandria, two Christian theologians from Alexandria, Egypt. The most important of these controversies concerned the relationship between the substance of God the Father and the substance of His Son.

Cecropius of Nicomedia was a bishop of Nicomedia and a key player in the Arian controversy.

Arian creeds are the creeds of Arian Christians, developed mostly in the fourth century when Arianism was one of the main varieties of Christianity.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacques Zeiller, Les origines chrétiennes dans les provinces danubiennes de l'Empire romain (Paris: E. de Boccard, 1918), pp. 143–45.

- 1 2 Yves-Marie Duval, "Aquilée et Sirmium durant la crise arienne", Antichità Altoadriatiche26, 2 (1985): 345–54.

- ↑ R. C. P. Hanson, The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy 318–381 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005 [1988]), p. 156.

- ↑ Ernest Honigmann, "Une list inédite des pères de Nicée: Cod. Vatic. Gr. 1587, fol. 355r–357v", Byzantion, 20 (1950), pp. 63–71, no. 186 at p. 67: δόμνος πανονίας.

- ↑ Carlos R. Galvao-Sobrinho, Doctrine and Power: Theological Controversy and Christian Leadership in the Later Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2013), p. 103.

- ↑ Julia Valeva and Athanasios K. Vionis, "The Balkan Peninsula", in William Tabbernee (ed.), Early Christianity in Contexts: An Exploration across Cultures and Continents (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014), pp. 321–78, at 360.

- ↑ Maddalena Betti, The Making of Christian Moravia (858–882): Papal Power and Political Reality (Leiden: Brill, 2014), p. 198.

- ↑ Zeiller, Les origines, p. 598.

- ↑ J. N. D. Kelly, Jerome: His Life, Writings, and Controversies (Duckworth, 1975), p. 3, n. 6.