Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is more often used by the government of a single country to measure its economic health. Due to its complex and subjective nature, this measure is often revised before being considered a reliable indicator.

A variety of measures of national income and output are used in economics to estimate total economic activity in a country or region, including gross domestic product (GDP), gross national product (GNP), net national income (NNI), and adjusted national income. All are specially concerned with counting the total amount of goods and services produced within the economy and by various sectors. The boundary is usually defined by geography or citizenship, and it is also defined as the total income of the nation and also restrict the goods and services that are counted. For instance, some measures count only goods & services that are exchanged for money, excluding bartered goods, while other measures may attempt to include bartered goods by imputing monetary values to them.

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production process, i.e. output per unit of input, typically over a specific period of time. The most common example is the (aggregate) labour productivity measure, one example of which is GDP per worker. There are many different definitions of productivity and the choice among them depends on the purpose of the productivity measurement and data availability. The key source of difference between various productivity measures is also usually related to how the outputs and the inputs are aggregated to obtain such a ratio-type measure of productivity.

Value added is a term in financial economics for calculating the difference between market value of a product or service, and the sum value of its constituents. It is relatively expressed to the supply-demand curve for specific units of sale. It represents a market equilibrium view of production economics and financial analysis. Value added is distinguished from the accounting term added value which measures only the financial profits earned upon transformational processes for specific items of sale that are available on the market.

In economics, an input–output model is a quantitative economic model that represents the interdependencies between different sectors of a national economy or different regional economies. Wassily Leontief (1906–1999) is credited with developing this type of analysis and earned the Nobel Prize in Economics for his development of this model.

National accounts or national account systems (NAS) are the implementation of complete and consistent accounting techniques for measuring the economic activity of a nation. These include detailed underlying measures that rely on double-entry accounting. By design, such accounting makes the totals on both sides of an account equal even though they each measure different characteristics, for example production and the income from it. As a method, the subject is termed national accounting or, more generally, social accounting. Stated otherwise, national accounts as systems may be distinguished from the economic data associated with those systems. While sharing many common principles with business accounting, national accounts are based on economic concepts. One conceptual construct for representing flows of all economic transactions that take place in an economy is a social accounting matrix with accounts in each respective row-column entry.

Prices of production is a concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy, defined as "cost-price + average profit". A production price can be thought of as a type of supply price for products; it refers to the price levels at which newly produced goods and services would have to be sold by the producers, in order to reach a normal, average profit rate on the capital invested to produce the products.

Productive and unproductive labour are concepts that were used in classical political economy mainly in the 18th and 19th centuries, which survive today to some extent in modern management discussions, economic sociology and Marxist or Marxian economic analysis. The concepts strongly influenced the construction of national accounts in the Soviet Union and other Soviet-type societies.

Intermediate consumption is an economic concept used in national accounts, such as the United Nations System of National Accounts (UNSNA), the US National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) and the European System of Accounts (ESA).

Compensation of employees (CE) is a statistical term used in national accounts, balance of payments statistics and sometimes in corporate accounts as well. It refers basically to the total gross (pre-tax) wages paid by employers to employees for work done in an accounting period, such as a quarter or a year.

Net output is an accounting concept used in national accounts such as the United Nations System of National Accounts (UNSNA) and the NIPAs, and sometimes in corporate or government accounts. The concept was originally invented to measure the total net addition to a country's stock of wealth created by production during an accounting interval. The concept of net output is basically "gross revenue from production less the value of goods and services used up in that production". The idea is that if one deducts intermediate expenditures from the annual flow of income generated by production, one obtains a measure of the net new value in the new products created.

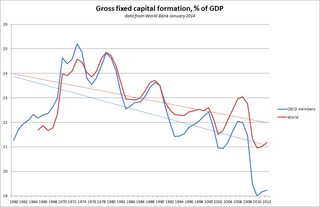

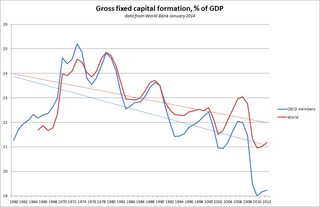

Capital formation is a concept used in macroeconomics, national accounts and financial economics. Occasionally it is also used in corporate accounts. It can be defined in three ways:

The distinction between real prices and ideal prices is a distinction between actual prices paid for products, services, assets and labour, and computed prices which are not actually charged or paid in market trade, although they may facilitate trade. The difference is between actual prices paid, and information about possible, potential or likely prices, or "average" price levels. This distinction should not be confused with the difference between "nominal prices" (current-value) and "real prices". It is more similar to, though not identical with, the distinction between "theoretical value" and "market price" in financial economics.

Domar aggregation is an approach to aggregating growth measures associated with industries to make larger sector or national aggregate growth rates. The issue comes up in the context of national accounts and multifactor productivity (MFP) statistics.

Aggregate income is the total of all incomes in an economy without adjustments for inflation, taxation, or types of double counting. Aggregate income is a form of GDP that is equal to Consumption expenditure plus net profits. 'Aggregate income' in economics is a broad conceptual term. It may express the proceeds from total output in the economy for producers of that output. There are a number of ways to measure aggregate income, but GDP is one of the best known and most widely used.

Productivity in economics is usually measured as the ratio of what is produced to what is used in producing it. Productivity is closely related to the measure of production efficiency. A productivity model is a measurement method which is used in practice for measuring productivity. A productivity model must be able to compute Output / Input when there are many different outputs and inputs.

The Keynesian cross diagram is a formulation of the central ideas in Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. It first appeared as a central component of macroeconomic theory as it was taught by Paul Samuelson in his textbook, Economics: An Introductory Analysis. The Keynesian cross plots aggregate income and planned total spending or aggregate expenditure.

Sectoral output for an industry or combination of industries ("sector") is the value of its output sold outside that sector. It is usually calculated as the value of the sector's gross output minus the value of shipments within the sector from one establishment to another.

The annual United Kingdom National Accounts records and describes economic activity in the United Kingdom and as such is used by government, banks, academics and industries to formulate the economic and social policies and monitor the economic progress of the United Kingdom. It also allows international comparisons to be made. The Blue Book is published by the UK Office for National Statistics alongside the United Kingdom Balance of Payments – The Pink Book.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.