Related Research Articles

The Soviet Union introduced forced collectivization of its agricultural sector between 1928 and 1940 during the ascension of Joseph Stalin. It began during and was part of the first five-year plan. The policy aimed to integrate individual landholdings and labour into nominally collectively-controlled and openly or directly state-controlled farms: Kolkhozes and Sovkhozes accordingly. The Soviet leadership confidently expected that the replacement of individual peasant farms by collective ones would immediately increase the food supply for the urban population, the supply of raw materials for the processing industry, and agricultural exports via state-imposed quotas on individuals working on collective farms. Planners regarded collectivization as the solution to the crisis of agricultural distribution that had developed from 1927. This problem became more acute as the Soviet Union pressed ahead with its ambitious industrialization program, meaning that more food would be needed to keep up with urban demand.

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a human-made famine in Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–1933 which affected the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union.

Throughout Russian history famines, droughts and crop failures occurred on the territory of Russia, the Russian Empire and the USSR on more or less regular basis. From the beginning of the 11th to the end of the 16th century, on the territory of Russia for every century there were 8 crop failures, which were repeated every 13 years, sometimes causing prolonged famine in a significant territory. The causes of the famine were different, from natural and economic and political crises; for example, the Great Famine of 1931–1933, colloquially called the Holodomor, the cause of which was, among other factors, the collectivization policy in the USSR, which affected the territory of the Volga region in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

The Soviet famine of 1930–1933 was a famine in the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine and different parts of Russia, including Kazakhstan, Northern Caucasus, Kuban Region, Volga Region, the South Urals, and West Siberia. Major factors included the forced collectivization of agriculture as a part of the First Five-Year Plan and forced grain procurement from farmers. These factors in conjunction with a massive investment in heavy industry decreased the agricultural workforce. Estimates conclude that 5.7 to 8.7 million people died from starvation across the Soviet Union. In addition 50 to 70 million Soviet citizens starved during the famine yet survived.

James E. Mace was an American historian, professor, and researcher of the Holodomor.

Holodomor denial is the claim that the Holodomor, a 1932–33 man-made famine that killed millions in Soviet Ukraine, did not occur or diminishing its scale and significance.

The International Commission of Inquiry Into the 1932–1933 Famine in Ukraine was set up in 1984 and was initiated by the World Congress of Free Ukrainians to study and investigate the 1932-1933 man-made famine that killed millions in Ukraine. Members of Commission selected and invited by World Congress of Free Ukrainians. None of them represent own country or country authority/institution and act as individual. Most of them are retired jurists, one of them died before Commission finish their investigations. The Commission was funded by donations from the worldwide Ukrainian diaspora.

In 1932–1933, a man-made famine, known as the Holodomor, killed 3.3–5 million people in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, included in a total of 5.5–8.7 million killed by the broader Soviet famine of 1930–1933. At least 3.3 million ethnic Ukrainians died as a result of the famine in the USSR. Scholars debate whether there was an intent to starve millions of Ukrainians to death or not.

The US Commission on the Ukraine Famine was a commission to study the Holodomor, a 1932–33 man-made famine that killed millions in Ukraine.

The Holodomor was a 1932–33 man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine and adjacent Ukrainian-inhabited territories that killed millions of Ukrainians. Opinions and beliefs about the Holodomor vary widely among nations. It is considered a genocide by Ukraine, and Ukraine's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has lobbied for the famine to be considered a genocide internationally. By 2022, the Holodomor was recognized as a genocide by the parliaments of 23 countries and the European Parliament, and it is recognized as a part of the Soviet famine of 1932–1933 by Russia. As of June 2023, 35 countries recognise the Holodomor as a genocide.

Grover Carr Furr III is an American professor of Medieval English literature at Montclair State University who is best known for his revisionist views regarding the Soviet Union and Joseph Stalin. Furr has written books, papers, and articles about Soviet history, especially the Stalin era, in which he has stated that the Holodomor, the 1932–33 famine in Soviet Ukraine, was not deliberate, describing it as a fiction created by pro-Nazi Ukrainian nationalists, that the Katyn massacre was committed by the Nazi Schutzstaffel and not the Soviet NKVD, that all defendants in the Moscow Trials were guilty as charged, that claims in Nikita Khrushchev's speech On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences are almost entirely false, that the purpose of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was to preserve the Second Polish Republic rather than partition it, and that the Soviet Union did not invade Poland in September 1939, on the grounds that the Polish state no longer existed. Furr claims that the mainstream narrative of the Soviet Union and in particular the Stalin era is biased and that many of the claims by mainstream historians are unfounded, because they follow "anti-Stalin paradigm".

The Great Turn or Great Break was the radical change in the economic policy of the USSR from 1928 to 1929, primarily consisting of the process by which the New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1921 was abandoned in favor of the acceleration of collectivization and industrialization and also a cultural revolution. The term came from the title of Joseph Stalin's article "Year of the Great Turn" published on November 7, 1929, the 12th anniversary of the October Revolution. David R. Marples argues that the era of the Great Break lasted until 1934.

Kulak, also kurkul or golchomag, was the term which was used to describe Petite bourgeoisie who owned over 3 ha of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and Azerbaijan, kulak referred to property ownership among petite bourgeoisie who were considered hesitant allies of the Bolshevik Revolution. In Ukraine during 1930–1931, there also existed a term of podkulachnik ; these were considered "sub-kulaks".

The Kazakh famine of 1930–1933, also known as the Asharshylyk, was a famine during which approximately 1.5 million people died in the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, then part of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic in the Soviet Union, of whom 1.3 million were ethnic Kazakhs. An estimated 38 to 42 percent of all Kazakhs died, the highest percentage of any ethnic group killed by the Soviet famine of 1930–1933. Other research estimates that as many as 2.3 million died. A committee created by the Kazakhstan parliament chaired by Historian Manash Kozybayev concluded that the famine was "a manifestation of the politics of genocide", with 1.75 million victims.

The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine is a 1986 book by British historian Robert Conquest published by the Oxford University Press. It was written with the assistance of historian James Mace, a junior fellow at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, who started doing research for the book following the advice of the director of the institute. Conquest wrote the book in order "to register in the public consciousness of the West a knowledge of and feeling for major events, involving millions of people and millions of deaths, which took place within living memory."

Holodomor: Voices of Survivors is a 2015 Canadian short documentary film by filmmaker Ariadna Ochrymovych about the 1932–33 Holodomor famine in Soviet Ukraine. It documents oral history from Ukrainian Canadian survivors of the Holodomor, which is recognized by Ukraine, Canada and 28 other countries as of 2023 as a genocide of the Ukrainian people carried out by the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. Ochrymovych conducted and filmed over 100 interviews across Canada.

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable to the Soviet revolutionary and dictator Joseph Stalin vary widely. The scholarly consensus affirms that archival materials declassified in 1991 contain irrefutable data far superior to sources used prior to 1991, such as statements from emigres and other informants.

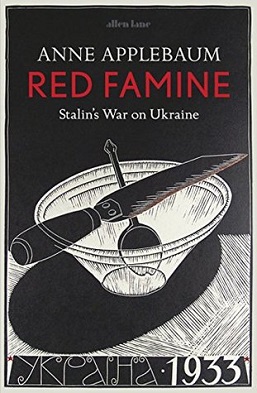

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine is a 2017 non-fiction book by American-Polish historian Anne Applebaum, focusing on the history of the Holodomor. The book won the Lionel Gelber Prize and the Duff Cooper Prize.

Fred Erwin Beal (1896–1954) was an American labor-union organizer whose critical reflections on his work and travel in the Soviet Union divided left-wing and liberal opinion. In 1929 he had been a cause célèbre when, in Gastonia, North Carolina, he was convicted in an irregular trial of conspiracy in the strike-related killing of a local police chief. But having escaped to the Soviet Union, his decision in 1933 to return and bear witness to the costs of Stalin's collectivist policies, including famine in Ukraine, was disparaged and resisted by many of his erstwhile supporters.

References

- ↑ Year of birth from Library of Congress bibliographic authority record

- ↑ The Library of Congress. "Holodomor denial literature - LC Linked Data Service: Authorities and Vocabularies | Library of Congress, from LC Linked Data Service: Authorities and Vocabularies". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ↑ Tottle, Douglas (1987). "Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard". Progress Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-919396-51-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Applebaum, Anne (2017). Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (1 ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 338. ISBN 9780385538855.

- ↑ Tottle, Douglas (1987). "Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard". Progress Books. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-919396-51-7.

- ↑ Sysyn, Frank (1999). "The Ukrainian Famine of 1932–3: The Role of the Ukrainian Diaspora in Research and Public Discussion". In Chorbajian, Levon; Shirinian, George (eds.). Studies in Comparative Genocide. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-312-21933-4. OCLC 39692229 . Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ↑ Marchak, Patricia (2003). Reigns of Terror. Montreal; Ithaca: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-7735-2642-0. OCLC 52459228 . Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ↑ Young, Cathy (April 13, 2017) [Original date October 31, 2015]. "Russia Denies Stalin's Killer Famine". The Daily Beast . Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ↑ "Kris i Ukraina 1932-1933". Klasskamp, historieförfalskning och den kapitalistiska förintelsen (in Swedish). Sveriges kommunistiska parti. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- 1 2 Sundberg, Jacob W.F. "International Commission of Inquiry Into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine. The Final Report (1990)". The Stockholm Institute of Public and International Law. Archived from the original on 4 December 2004. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Tottle, Douglas (1987). "Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard - About the Author". Progress Books. p. n1. ISBN 978-0-919396-51-7.

- 1 2 Douglas Tottle (1987). Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard. Progress Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-919396-51-7 . Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Tottle, Douglas (1987). "Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard". Toronto: Progress Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-919396-51-8.

- ↑ A.J. Hobbins, Daniel Boyer, "Seeking Historical Truth: the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-33 Famine in the Ukraine", Dalhousie Law Journalhh, 2001, Vol 24, page 166

- ↑ Report of the Commission p. 5 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)