Related Research Articles

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning—that is, to distinguish or to inflect words. All oral languages use pitch to express emotional and other para-linguistic information and to convey emphasis, contrast and other such features in what is called intonation, but not all languages use tones to distinguish words or their inflections, analogously to consonants and vowels. Languages that have this feature are called tonal languages; the distinctive tone patterns of such a language are sometimes called tonemes, by analogy with phoneme. Tonal languages are common in East and Southeast Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Pacific.

Ganda or Luganda is a Bantu language spoken in the African Great Lakes region. It is one of the major languages in Uganda and is spoken by more than 5.56 million Baganda and other people principally in central Uganda, including the country's capital, Kampala. Typologically, it is an agglutinative, tonal language with subject–verb–object word order and nominative–accusative morphosyntactic alignment.

A pitch-accent language is a type of language that, when spoken, has certain syllables in words or morphemes that are prominent, as indicated by a distinct contrasting pitch rather than by loudness or length, as in some other languages like English. Pitch-accent languages also contrast with fully tonal languages like Vietnamese, Thai and Standard Chinese, in which practically every syllable can have an independent tone. Some scholars have claimed that the term "pitch accent" is not coherently defined and that pitch-accent languages are just a sub-category of tonal languages in general.

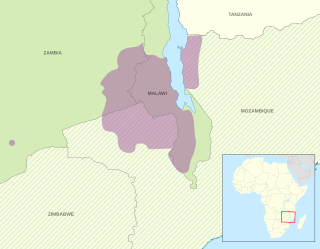

Chewa is a Bantu language spoken in Malawi and a recognised minority in Zambia and Mozambique. The noun class prefix chi- is used for languages, so the language is usually referred to as Chichewa and Chinyanja. In Malawi, the name was officially changed from Chinyanja to Chichewa in 1968 at the insistence of President Hastings Kamuzu Banda, and this is still the name most commonly used in Malawi today. In Zambia, the language is generally known as Nyanja or Cinyanja/Chinyanja '(language) of the lake'.

Ghotuo is a North Central Edoid language spoken in Edo State, mostly in the Owan and Akoko-Edo areas of Edo state, Nigeria.

Japanese pitch accent is a feature of the Japanese language that distinguishes words by accenting particular morae in most Japanese dialects. The nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects. For instance, the word for "river" is in the Tokyo dialect, with the accent on the second mora, but in the Kansai dialect it is. A final or is often devoiced to or after a downstep and an unvoiced consonant.

The Tumbuka language is a Bantu language which is spoken in Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. It is also known by the autonym Chitumbuka also spelled Citumbuka — the chi- prefix in front of Tumbuka means "in the manner of", and is understood in this case to mean "the language of the Tumbuka people". Tumbuka belongs to the same language group as Chewa and Sena.

Meeussen's rule is a special case of tone reduction. It was first described in Bantu languages, but occurs in analyses of other languages as well, such as Papuan languages. The tonal alternation it describes is the lowering, in some contexts, of the last tone of a pattern of two adjacent High tones (HH), resulting in the pattern HL. The phenomenon is named after its first observer, the Belgian Bantu specialist A. E. Meeussen (1912–1978). In phonological terms, the phenomenon can be seen as a special case of the Obligatory Contour Principle.

Downstep is a phenomenon in tone languages in which if two syllables have the same tone, the second syllable is lower in pitch than the first.

In linguistics, upstep is a phonemic or phonetic upward shift of tone between the syllables or words of a tonal language. It is best known in the tonal languages of Sub-Saharan Africa. Upstep is a much rarer phenomenon than its counterpart, downstep.

Tone terracing is a type of phonetic downdrift, where the high or mid tones, but not the low tone, shift downward in pitch (downstep) after certain other tones. The result is that a tone may be realized at a certain pitch over a short stretch of speech shifts downward, then continues at its new level and then shifts downward again until the end of the prosodic contour is reached, at which point the pitch resets. A graph of the change in pitch over time of a particular tone resembles a terrace.

INTSINT is an acronym for INternational Transcription System for INTonation.

Ikwerre, sometimes spelt as Ikwere, is an Igbo language spoken primarily by the Ikwerre people, who inhabit certain areas of Rivers State, Nigeria. It is also the biggest Igbo language along with Ngwa in Abia State.

Like most other Niger–Congo languages, Sesotho is a tonal language, spoken with two basic tones, high (H) and low (L). The Sesotho grammatical tone system is rather complex and uses a large number of "sandhi" rules.

In speech, phonetic pitch reset occurs at the boundaries (pausa) between prosodic units.

Malawi Lomwe, known as Elhomwe, is a dialect of the Lomwe language spoken in southeastern Malawi in parts such as Mulanje and Thyolo.

Chichewa is the main language spoken in south and central Malawi, and to a lesser extent in Zambia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Like most other Bantu languages, it is tonal; that is to say, pitch patterns are an important part of the pronunciation of words. Thus, for example, the word chímanga (high-low-low) 'maize' can be distinguished from chinangwá (low-low-high) 'cassava' not only by its consonants but also by its pitch pattern. These patterns remain constant in whatever context the nouns are used.

The term boundary tone refers to a rise or fall in pitch that occurs in speech at the end of a sentence or other utterance, or, if a sentence is divided into two or more intonational phrases, at the end of each intonational phrase. It can also refer to a low or high intonational tone at the beginning of an utterance or intonational phrase.

Luganda, the language spoken by the Baganda people from Central Uganda, is a tonal language of the Bantu family. It is traditionally described as having three tones: high, low and falling. Rising tones are not found in Luganda, even on long vowels, since a sequence such as [] automatically becomes [].

Medumba phonology is the way in which the Medumba language is pronounced. It deals with phonetics, phonotactics and their variation across different dialects of Medumba.