Related Research Articles

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme is a set of phones that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning—that is, to distinguish or to inflect words. All oral languages use pitch to express emotional and other para-linguistic information and to convey emphasis, contrast and other such features in what is called intonation, but not all languages use tones to distinguish words or their inflections, analogously to consonants and vowels. Languages that have this feature are called tonal languages; the distinctive tone patterns of such a language are sometimes called tonemes, by analogy with phoneme. Tonal languages are common in East and Southeast Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Pacific.

Kirundi, also known as Rundi, is a Bantu language and the national language of Burundi. It is a dialect of Rwanda-Rundi dialect continuum that is also spoken in Rwanda and adjacent parts of Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, as well as in Kenya. Kirundi is mutually intelligible with Kinyarwanda, the national language of Rwanda, and the two form parts of the wider dialect continuum known as Rwanda-Rundi.

A pitch-accent language is a type of language that, when spoken, has certain syllables in words or morphemes that are prominent, as indicated by a distinct contrasting pitch rather than by loudness or length, as in some other languages like English. Pitch-accent languages also contrast with fully tonal languages like Vietnamese, Thai and Standard Chinese, in which practically every syllable can have an independent tone. Some scholars have claimed that the term "pitch accent" is not coherently defined and that pitch-accent languages are just a sub-category of tonal languages in general.

Ghotuo is a North Central Edoid language spoken in Edo State, mostly in the Owan and Akoko-Edo areas of Edo state, Nigeria.

Meeussen's rule is a special case of tone reduction. It was first described in Bantu languages, but occurs in analyses of other languages as well, such as Papuan languages. The tonal alternation it describes is the lowering, in some contexts, of the last tone of a pattern of two adjacent High tones (HH), resulting in the pattern HL. The phenomenon is named after its first observer, the Belgian Bantu specialist A. E. Meeussen (1912–1978). In phonological terms, the phenomenon can be seen as a special case of the Obligatory Contour Principle.

Mongsen Ao is a member of the Ao languages, a branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages, predominantly spoken in central Mokokchung district of Nagaland, northeast India. Its speakers see the language as one of two varieties of a greater "Ao language," along with the prestige variety Chungli Ao.

Larry M. Hyman is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at the University of California, Berkeley. He specializes in phonology and has particular interest in African languages.

Downstep is a phenomenon in tone languages in which if two syllables have the same tone, the second syllable is lower in pitch than the first.

A floating tone is a morpheme or element of a morpheme that contains neither consonants nor vowels, but only tone. It cannot be pronounced by itself but affects the tones of neighboring morphemes.

The Ekoid languages are a dialect cluster of Southern Bantoid languages spoken principally in southeastern Nigeria and in adjacent regions of Cameroon. They have long been associated with the Bantu languages, without their status being precisely defined. Crabb (1969) remains the major monograph on these languages, although regrettably, Part II, which was to contain grammatical analyses, was never published. Crabb also reviews the literature on Ekoid up to the date of publication.

Gokana (Gòkánà) is an Ogoni language spoken by some 130,000 people in Rivers State, Nigeria.

In linguistics, a prosodic unit is a segment of speech that occurs with specific prosodic properties. These properties can be those of stress, intonation, or tonal patterns.

Tone letters are letters that represent the tones of a language, most commonly in languages with contour tones.

Izi is an Igboid language spoken in Ebonyi state in Nigeria. It forms a dialect cluster with the closely related languages Ikwo, Ezza, and Mgbo.

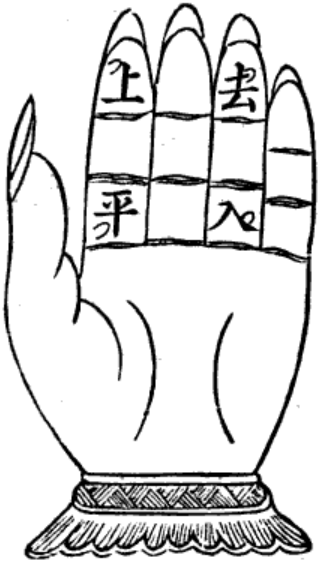

The four tones of Chinese poetry and dialectology are four traditional tone classes of Chinese words. They play an important role in Chinese poetry and in comparative studies of tonal development in the modern varieties of Chinese, both in traditional Chinese and in Western linguistics. They correspond to the phonology of Middle Chinese, and are named even or level, rising, departing or going, and entering or checked. They are reconstructed as mid, mid rising, high falling, and mid with a final stop consonant respectively. Due to historic splits and mergers, none of the modern varieties of Chinese have the exact four tones of Middle Chinese, but they are noted in rhyming dictionaries.

Jita is a Bantu language of Tanzania, spoken on the southeastern shore of Lake Victoria/Nyanza and on the island of Ukerewe.

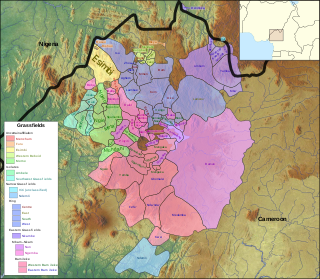

Babanki, or Kejom, is a Bantoid language that is spoken by the Babanki people of the Western Highlands of Cameroon.

Obokuitai (Obogwitai) is a Lakes Plain language of Papua, Indonesia. It is named after Obogwi village in East Central Mambermano District, Mamberamo Raya Regency.

Laura J. Downing is an American linguist, specializing in the phonology of African languages.

References

- ↑ Puech, Gilbert (1990). Upstep in a Bantu tone language. Pholia 5.175-1186.

- ↑ Puech 1990

- ↑ Snider, Keith Tonal 'upstep' in Engenni. Journal of West African Languages 27:1.3-15.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry (1993). Register tones and tonal geometry. In ed. Harry van der Hulst & Keith L. Snider, The Phonology of Tone: The Representation of Tonal Register, 85-89. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ↑ Thomas, Elaine (1974). Engenni. In Ten Nigerian tone systems. Studies in Nigerian Languages, Vol. 4. (ed.) John Bendor-Samuel. Jos and Kano: Institute of Linguistics and Centre for the Study of Nigerian Languages.

- ↑ Thomas, Elaine (1978). A grammatical description of the Engenni language. Arlington TX: University of Texas at Arlington and SIL.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry (1993). Register tones and tonal geometry. In ed. Harry van der Hulst & Keith L. Snider, The Phonology of Tone: The Representation of Tonal Register, 94-103. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ↑ Snider, Keith L. (1990). Tonal Upstep in Krachi: Evidence for a Register Tier. In The geometry and features of tone. Dallas: SIL and University of Texas at Arlington.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry (1993). Register tones and tonal geometry. In ed. Harry van der Hulst & Keith L. Snider, The Phonology of Tone: The Representation of Tonal Register, 89-94. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ↑ Leroy, Jacqueline (1977). Morphologie et classes nominales in mankon. Paris: Société d'Etudes Linguistiques et Anthropologiques de France.

- ↑ Leroy, Jacqueline (1979). A la recherche de tons perdus: structure tonal du nom en ngemba. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 1.31-54.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry & Maurice Tadadjeu (1976). Floating tones in Mbam-Nkam. In ed. Larry Hyman, Studies in Bantu Tonology. University of Southern California: Occasional Papers in Linguistics.

- ↑ Mellick, Christina (2012). Tone in the Mbelime verb system. Dallas, TX: Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics. Masters thesis, p. 82-84

- ↑ Wilhelmsen, Vera (2013). Upstep in Mbugwe: a description of upstep in Mbugwe verbs. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on Bantu Languages, Paris.

- ↑ Wilhelmsen 2013

- ↑ Jason Kandybowicz (2008). The Grammar of Repetition: Nupe grammar at the syntax–phonology interface. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- ↑ Yip, Moira (2002). Tone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 217-219