Niger–Congo is a hypothetical language family spoken over the majority of sub-Saharan Africa. It unites the Mande languages, the Atlantic-Congo languages, and possibly several smaller groups of languages that are difficult to classify. If valid, Niger-Congo would be the world's largest in terms of member languages, the third-largest in terms of speakers, and Africa's largest in terms of geographical area. It is generally considered to be the world's largest language family in terms of the number of distinct languages, just ahead of Austronesian, although this is complicated by the ambiguity about what constitutes a distinct language; the number of named Niger–Congo languages listed by Ethnologue is 1,540.

The Kwa languages, often specified as New Kwa, are a proposed but as-yet-undemonstrated family of languages spoken in the south-eastern part of Ivory Coast, across southern Ghana, and in central Togo. The Kwa family belongs to the Niger-Congo phylum. The name was introduced 1895 by Gottlob Krause and derives from the word for 'people' (Kwa) in many of these languages, as illustrated by Akan names. This branch consists of around 50 different languages spoken by about 25 million people. Some of the largest Kwa languages are Ewe, Akan and Baule.

Benue–Congo is a major branch of the Volta-Congo languages which covers most of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Southern Bantoid is a branch of the Bantoid language family. It consists of the Bantu languages along with several small branches and isolates of eastern Nigeria and west-central Cameroon. Since the Bantu languages are spoken across most of Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern Bantoid comprises 643 languages as counted by Ethnologue, though many of these are mutually intelligible.

Bantoid is a major branch of the Benue–Congo language family. It consists of the Northern Bantoid languages and the Southern Bantoid languages, a division which also includes the Bantu languages that constitute the overwhelming majority and after which Bantoid is named.

The Tivoid languages are a branch of the Southern Bantoid languages spoken in parts of Nigeria and Cameroon. The subfamily takes its name after Tiv, the most spoken language in the group.

The Beboid languages are any of several groups of languages spoken principally in southwest Cameroon, although two languages are spoken over the border in Nigeria. They are probably not most closely related to each other. The Eastern Beboid languages may be most closely related to the Tivoid and Momo groups, though some of the geographical Western Beboid grouping may be closer to Ekoid and Bantu.

The Ekoid languages are a dialect cluster of Southern Bantoid languages spoken principally in southeastern Nigeria and in adjacent regions of Cameroon. They have long been associated with the Bantu languages, without their status being precisely defined. Crabb (1969) remains the major monograph on these languages, although regrettably, Part II, which was to contain grammatical analyses, was never published. Crabb also reviews the literature on Ekoid up to the date of publication.

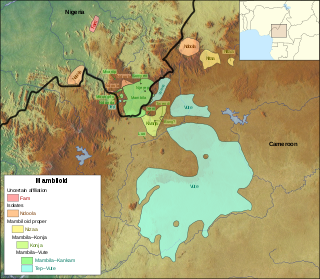

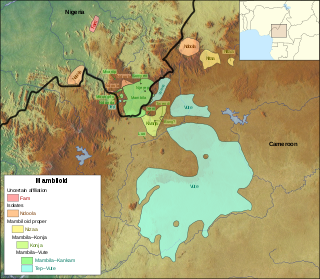

The twelve Mambiloid languages are languages spoken by the Mambila and related peoples mostly in eastern Nigeria and in Cameroon. In Nigeria the largest group is Mambila. In Cameroon the largest group is Vute.

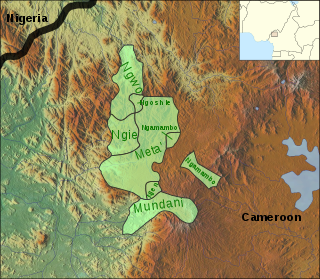

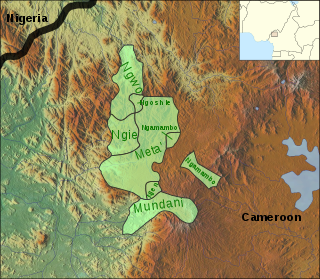

The Southwest Grassfields, traditionally called Western Momo when considered part of the Momo group or when Momo is included in Grassfields, are a small branch of the Southern Bantoid languages spoken in the Western grassfields of Cameroon.

The Momo languages are a group of Grassfields languages spoken in the Western High Plateau of Cameroon.

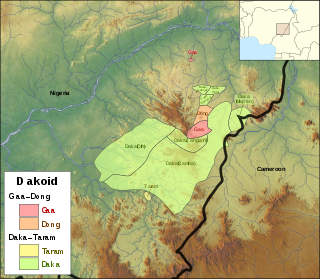

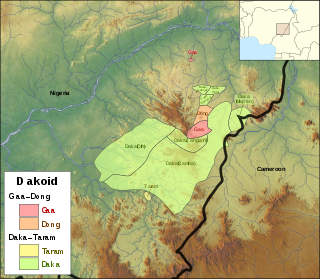

The Dakoid languages are a branch of the Northern Bantoid languages spoken in Taraba and Adamawa states of eastern Nigeria.

Naki, or Munkaf, is an Eastern Beboid language of Cameroon and Nigeria. There is no name for the language; it is known by the villages it is spoken in, including Naki and Mekaf (Munkaf) in Cameroon and Bukwen and Mashi in Nigeria, the latter listed as separate languages by Ethnologue, though they are not distinct.

Fang is a Southern Bantoid language of Cameroon.

Koshin is a Southern Bantoid language of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but that has not been demonstrated to be a valid family.

Mbuʼ, or Ajumbu, is a Southern Bantoid language of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but that has not been demonstrated to be a valid family. Inasmuch as Western Beboid may be valid, Mbuʼ would appear to be the most divergent of its languages.

Amasi is a Southern Bantoid language of Cameroon.

Iyive, also referred to as Uive, Yiive, Ndir, Asumbos, is a severely endangered Bantoid language spoken in Nigeria and Cameroon. The ethnic group defined by use of this language is the Ndir.

Proto-Bantu is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Bantu languages, a subgroup of the Southern Bantoid languages. It is thought to have originally been spoken in West/Central Africa in the area of what is now Cameroon. About 6,000 years ago, it split off from Proto-Southern Bantoid when the Bantu expansion began to the south and east. Two theories have been put forward about the way the languages expanded: one is that the Bantu-speaking people moved first to the Congo region and then a branch split off and moved to East Africa; the other is that the two groups split from the beginning, one moving to the Congo region, and the other to East Africa.

Northern Bantoid is a branch of the Bantoid languages. It consists of the Mambiloid, Dakoid, and Tikar languages of eastern Nigeria and west-central Cameroon.