Related Research Articles

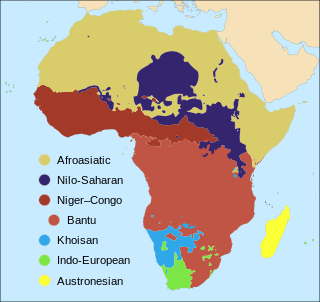

The number of languages natively spoken in Africa is variously estimated at between 1,250 and 2,100, and by some counts at over 3,000. Nigeria alone has over 500 languages, one of the greatest concentrations of linguistic diversity in the world. The languages of Africa belong to many distinct language families, among which the largest are:

The West Atlantic languages of West Africa are a major subgroup of the Niger–Congo languages.

The Mande languages are a group of languages spoken in several countries in West Africa by the Mandé peoples. These include; Maninka, Mandinka, Soninke, Bambara, Kpelle, Jula, Bozo, Mende, Susu, and Vai. There are around 60 to 75 languages spoken by 30 to 40 million people, chiefly in; Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, the Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Mauritania, Ghana and also in northwestern Nigeria and northern Benin.

The Manding languages are a dialect continuum within the Mande language family spoken in West Africa. Varieties of Manding are generally considered to be mutually intelligible – dependent on exposure or familiarity with dialects between speakers – and spoken by 9 million people in the countries Burkina Faso, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Liberia, Ivory Coast and the Gambia. Their best-known members are Mandinka or Mandingo, the principal language of The Gambia; Bambara, the most widely spoken language in Mali; Maninka or Malinké, a major language of Guinea and Mali; and Jula, a trade language of Ivory Coast and western Burkina Faso. Manding is part of the larger Mandé family of languages.

Fula, also known as Fulani or Fulah, is a Senegambian language spoken by around 36.8 million people as a set of various dialects in a continuum that stretches across some 18 countries in West and Central Africa. Along with other related languages such as Serer and Wolof, it belongs to the Atlantic geographic group within Niger–Congo, and more specifically to the Senegambian branch. Unlike most Niger-Congo languages, Fula does not have tones.

The Atlantic–Congo languages are the largest demonstrated family of languages in Africa. They have characteristic noun class systems and form the core of the Niger–Congo family hypothesis. They comprise all of Niger–Congo apart from Mande, Dogon, Ijoid, Siamou, Kru, the Katla and Rashad languages, and perhaps some or all of the Ubangian languages. Hans Günther Mukarovsky's "Western Nigritic" corresponded roughly to modern Atlantic–Congo.

Senegal is a multilingual country: Ethnologue lists 36 languages, Wolof being the most widely spoken language.

The Ubangian languages form a diverse linkage of some seventy languages centered on the Central African Republic and the DR Congo. They are the predominant languages of the CAR, spoken by 2–3 million people, including one of its official languages, Sango. They are also spoken in Cameroon, Chad, the Republic of Congo and South Sudan.

The Senegambian languages, traditionally known as the Northern West Atlantic, or in more recent literature sometimes confusingly as the Atlantic languages, are a branch of Atlantic–Congo languages centered on Senegal, with most languages spoken there and in neighboring southern Mauritania, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Guinea. The transhumant Fula, however, have spread with their languages from Senegal across the western and central Sahel. The most populous unitary language is Wolof, the national language of Senegal, with four million native speakers and millions more second-language users. There are perhaps 13 million speakers of the various varieties of Fula, and over a million speakers of Serer. The most prominent feature of the Senegambian languages is that they are devoid of tone, unlike the vast majority of Atlantic-Congo languages.

The Ngbandi language is a dialect continuum of the Ubangian family spoken by a half-million or so people in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in the Central African Republic. It is primarily spoken by the Ngbandi people, which included the dictator of what was then known as Zaire, Mobutu Sese Seko.

Lunguda (Nʋngʋra) is a Niger–Congo language spoken in Nigeria. They settle western part of Gongola mainly in and around the hills of the volcanic Lunguda Plateau, Adamawa state. Joseph Greenberg counted it as a distinct branch, G10, within the Adamawa family. When Blench (2008) broke up Adamawa, Lunguda was made a branch of the Bambukic languages.

The Siamou language, also known as Seme (Sɛmɛ), is a language spoken mainly in Burkina Faso. It is part of the Kru languages or unclassified within the proposed Niger–Congo languages. It is also spoken in Ivory Coast and Mali, and could likely be a language isolate.

The Kwasio language, also known as Ngumba / Mvumbo, Bujeba, and Gyele / Kola, is a language of Cameroon, spoken in the south along the coast and at the border with Equatorial Guinea by some 70,000 members of the Ngumba, Kwasio, Gyele and Mabi peoples. Many authors view Kwasio and the Gyele/Kola language as distinct. In the Ethnologue, the languages therefore receive different codes: Kwasio has the ISO 639-3 code nmg, while Gyele has the code gyi. The Kwasio, Ngumba, and Mabi are village farmers; the Gyele are nomadic Pygmy hunter-gatherers living in the rain forest.

Balanta is a group of two closely related Bak languages of West Africa spoken by the Balanta people.

Nunez River or Rio Nuñez (Kakandé) is a river in Guinea with its source in the Futa Jallon highlands. It is also known as the Tinguilinta River, after a village along its upper course.

Sua, also known by other ethnic groups as Mansoanka or Kunante, is a divergent Niger–Congo language spoken in the Mansôa area of Guinea-Bissau.

Mbulungish is a Rio Nunez language of Guinea. Its various names include Baga Foré, Baga Monson, Black Baga, Bulunits, Longich, Monchon, Monshon. Wilson (2007) also lists the names Baga Moncõ. The language is called Ciloŋic (ci-lɔŋic) by its speakers, who refer to themselves as the Buloŋic (bu-lɔŋic).

Mboteni, also known as Baga Mboteni, Baga Binari, or Baga Pokur, is an endangered Rio Nunez language spoken in the coastal Rio Nunez region of Guinea. Speakers who have gone to school or work outside their villages are bilingual in Pokur and the Mande language Susu.

Miyobe or Soruba is an unclassified Niger-Congo language of Benin and Togo.

The Rio Nunez or Nunez River languages constitute a pair of Niger–Congo languages, Mbulungish and Baga Mboteni. They are spoken at the mouth of the Nunez River in Guinea, West Africa.

References

- ↑ Nalu at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilson, William André Auquier. 2007. Guinea Languages of the Atlantic group: description and internal classification. (Schriften zur Afrikanistik, 12.) Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- 1 2 "Did you know Nalu is vulnerable?". Endangered Languages. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ↑ Seidel, Frank (2012). "Language Documentation of Nalu in Guinea, West Africa" (PDF). Center for African Studies Research Report: 18.

- ↑ Hair, P. E. H. (1967). "Ethnolinguistic Continuity on the Guinea Coast". The Journal of African History. 8 (2): 253. doi:10.1017/s0021853700007040. JSTOR 179482. S2CID 161528479.

- ↑ Güldemann, Tom (2018). "Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa". In Güldemann, Tom (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of Africa. The World of Linguistics series. Vol. 11. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 58–444. doi:10.1515/9783110421668-002. ISBN 978-3-11-042606-9. S2CID 133888593.

- ↑ "Nalu". The Endangered Languages Project. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ↑ Simons, G. & Fennig, C. "Nalu". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Rodney, Walter (1970). A History of the Upper Guinea Coast. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Seidel, Frank (2017). "Nalu Language Archive". Endangered Languages Archive. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ↑ Appiah, K. & Gates, H. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 213.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Project Gallery". Endangered Language Documentation Programme. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- 1 2 3 4 Voeltz, F. K. Erhard (1996). "Les Langues de la Guinée". Cahiers d'Étude des Langues Guinéennes. 1: 24–25.

- 1 2 Johnston, H (1919). A Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages. Clarendon Press: Oxford. pp. 750–772).