Related Research Articles

Stephen Donaldson, born Robert Anthony Martin Jr. and also known by the pseudonym Donny the Punk, was an American bisexual rights activist, and political activist. He is best known for his pioneering activism in LGBT rights and prison reform, and for his writing about punk rock and subculture.

The Daughters of Bilitis, also called the DOB or the Daughters, was the first lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. The organization, formed in San Francisco in 1955, was initially conceived as a secret social club, an alternative to lesbian bars, which were subject to raids and police harassment.

The homophile movement is a collective term for the main organisations and publications supporting and representing sexual minorities in the 1950s to 1960s around the world. The name comes from the term homophile, which was commonly used by these organisations in an effort to deemphasized the sexual aspect of homosexuality. At least some of these organisations are considered to have been more cautious than both earlier and later LGBT organisations; in the U.S., the nationwide coalition of homophile groups disbanded after older members clashed with younger members who had become more radical after the Stonewall riots of 1969.

Founded in 1952, One Institute, is the oldest active LGBTQ+ organization in the United States, dedicated to telling LGBTQ+ history and stories through education, arts, and social justice programs. Since its inception, the organization has been headquartered in Los Angeles, California.

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s in the Western world, that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride. In the feminist spirit of the personal being political, the most basic form of activism was an emphasis on coming out to family, friends, and colleagues, and living life as an openly lesbian or gay person.

William Dorr Lambert Legg, known as W. Dorr Legg, was an American landscape architect and one of the founders of the United States gay rights movement, then called the homophile movement.

The Society for Human Rights was an American gay-rights organization established in Chicago in 1924. Society founder Henry Gerber was inspired to create it by the work of German doctor Magnus Hirschfeld and the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and by the organisation Bund für Menschenrecht by Friedrich Radszuweit and Karl Schulz in Berlin. It was the first recognized gay rights organization in the United States, having received a charter from the state of Illinois, and produced the first American publication for homosexuals, Friendship and Freedom. A few months after being chartered, the group ceased to exist in the wake of the arrest of several of the Society's members. Despite its short existence and small size, the Society has been recognized as a precursor to the modern gay liberation movement.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the 1960s.

LGBTQ movements in the United States comprise an interwoven history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer social movements in the United States of America, beginning in the early 20th century. A commonly stated goal among these movements is social equality for LGBTQ people. Some have also focused on building LGBTQ communities or worked towards liberation for the broader society from biphobia, homophobia, and transphobia. LGBTQ movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, including lobbying, street marches, social groups, media, art, and research. Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes:

For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies in order to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm.

LGBTQ rights organizations are non-governmental civil rights, health, and community organizations that promote the civil and human rights and health of sexual minorities, and to improve the LGBTQ community.

Craig L. Rodwell was an American gay rights activist known for founding the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop on November 24, 1967 - the first bookstore devoted to gay and lesbian authors - and as the prime mover for the creation of the New York City gay pride demonstration. Rodwell, who was already an activist when he participated in the 1969 Stonewall uprising, is considered by some to be the leading gay rights activist in the early, pre-Stonewall, homophile movement of the 1960s.

The North American Conference of Homophile Organizations was an umbrella organization for a number of homophile organizations. Founded in 1966, the goal of NACHO was to expand coordination among homophile organizations throughout the Americas. Homophile activists were motivated in part by an increase in mainstream media attention to gay issues. Some feared that without a centralized organization, the movement would be hijacked, in the words of founding member Foster Gunnison Jr., by "fringe elements, beatniks, and other professional non-conformists".

Henry Gerber was an early gay rights activist in the United States. Inspired by the work of Germany's Magnus Hirschfeld and his Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and by the organisation Bund für Menschenrecht by Friedrich Radszuweit and Karl Schulz, Gerber founded the Society for Human Rights (SHR) in 1924, the nation's first known gay organization, and Friendship and Freedom, the first known American gay publication. SHR was short-lived, as police arrested several of its members shortly after it incorporated. Although embittered by his experiences, Gerber maintained contacts within the fledgling homophile movement of the 1950s and continued to agitate for the rights of homosexuals. Gerber has been repeatedly recognized for his contributions to the LGBT movement.

Ernestine Eckstein was an African-American woman who helped steer the United States Lesbian and Gay rights movement during the 1960s. She was a leader in the New York chapter of Daughters of Bilitis (DOB). Her influence helped the DOB move away from negotiating with medical professionals and towards tactics of public demonstrations. Her understanding of, and work in, the Civil Rights Movement lent valuable experience on public protest to the lesbian and gay movement. Eckstein worked among activists such as Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, Barbara Gittings, Franklin Kameny, and Randy Wicker. In the 1970s she became involved in the black feminist movement, in particular the organization Black Women Organized for Action (BWOA).

East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO) was established in January 1962 in Philadelphia, to facilitate cooperation between homophile organizations and outside administrations. Its formative membership included the Mattachine Society chapters in New York and Washington D.C., the Daughters of Bilitis chapter in New York, and the Janus Society in Philadelphia, which met monthly. Philadelphia was chosen to be the host city, due to its central location among all involved parties.

William B. Kelley was a gay activist and lawyer from Chicago, Illinois. Many laud him as an important figure in gaining rights for gay people in the United States, as he was actively involved in gay activism for 50 years.

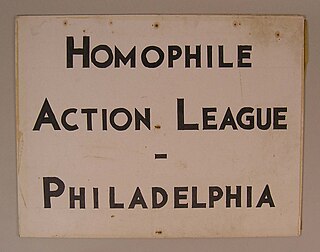

The Homophile Action League (HAL) was established in 1968 in Philadelphia as part of the Homophile movement in the United States. The organization advocated for the rights of the LGBT community and served as a predecessor to the Gay Liberation Front.

Queer radicalism can be defined as actions taken by queer groups which contribute to a change in laws and/or social norms. The key difference between queer radicalism and queer activism is that radicalism is often disruptive and commonly involves illegal action. Due to the nature of LGBTQ+ laws around the world, almost all queer activism that took place before the decriminalization of gay marriage can be considered radical action. The history of queer radicalism can be expressed through the many organizations and protests that contributed to a common cause of improving the rights and social acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community.

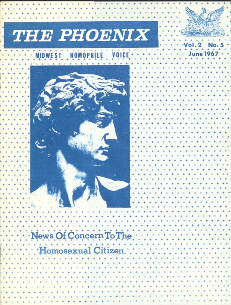

The Phoenix: Midwest Homophile Voice was an American homophile magazine that ran from 1966 to 1972. It was published by The Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom, in Kansas City, Missouri, and was the first LGBT magazine in the Midwest. The magazine was founded by Drew Shafer, a gay rights activist from Kansas City (KC), who was known for bringing the homophile movement to KC. The magazine's motto was: “Rising From the Fiery Hell of Social Injustice, The Wings of Freedom Will Never Be Stilled.”

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Scharlau, Kevin. "Drew Robert Shafer – Profiles in Kansas City Activism" . Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Martin, Mackenzie (2022-06-01). "Before Stonewall, this Kansas City activist helped unite the national gay rights movement". KCUR - Kansas City news and NPR. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Pfleger, Michael (2015-08-30). "A tribute to Drew Robert Shafer, founder of The Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom". The Tangent Group. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom". Making History. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ↑ Plake, Sarah (2021-06-16). "Pride Month History: Kansas City had foundational role in LGBT movement nationwide". KSHB 41 Kansas City News. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ↑ Colton, James; Peters, Cyril; Martin, Marcel; Barrow, Marilyn (October 1, 1968). "Tangents". Tangents. 3 (1): 24 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 "The Phoenix Society and the Homophile Movement". Making History. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ↑ "The Phoenix Society in Kansas City". Making History. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ↑ Osborn, Bradley (October 28, 2011). "Entertainer and Activist Returns to Town - OutVoices". outvoices.us. Retrieved 2023-06-05.