Related Research Articles

The Ptolemaic dynasty, also known as the Lagid dynasty, was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Reigning for 275 years, the Ptolemaic was the longest and last dynasty of ancient Egypt from 305 BC until its incorporation into the Roman Republic in 30 BC.

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus was a king of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt who ruled from 80 to 58 BC and then again from 55 BC until his death in 51 BC. He was commonly known as Auletes, referring to his love of playing the flute in Dionysian festivals. A member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, he was a descendant of its founder Ptolemy I, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great.

Cleopatra V was a Ptolemaic Queen of Egypt. She is the only surely attested wife of Ptolemy XII. Her only known child is Berenice IV, but she was also probably the mother of Cleopatra VII. It is unclear if she died around the time of Cleopatra VII's birth in 69 BC, or if it was her or a daughter named Cleopatra VI who co-ruled Ptolemaic Egypt with Berenice IV in 58–57 BC during the political exile of Ptolemy XII to Rome. No written records about Cleopatra V exist after 57 BC and two years later Berenice IV was overthrown by Ptolemy XII, his throne restored with Roman military aid.

The Elephantine Papyri and Ostraca consist of thousands of documents from the Egyptian border fortresses of Elephantine and Aswan, which yielded hundreds of papyri and ostraca in hieratic and demotic Egyptian, Aramaic, Koine Greek, Latin and Coptic, spanning a period of 100 years in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE. The documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives, and are thus an invaluable source of knowledge for scholars of varied disciplines such as epistolography, law, society, religion, language and onomastics. The Elephantine documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives: divorce documents, the manumission of slaves, and other business. The dry soil of Upper Egypt preserved the documents.

Ptolemy X Alexander I was the Ptolemaic king of Cyprus from 114 BC until 107 BC and of Egypt from 107 BC until his death in 88 BC. He ruled in co-regency with his mother Cleopatra III as Ptolemy Philometor Soter until 101 BC, and then with his niece and wife Berenice III as Ptolemy Philadelphus. He was a son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III, and younger brother of Ptolemy IX. His birth name was probably Alexander.

Leonidas II was the 28th Agiad King of Sparta from 254 to 242 BC and from 241 to 235 BC.

Zenon or Zeno, son of Agreophon, was a public official in Ptolemaic Egypt around the 250s-230s BC. He is known from a cache of his papyrus documents which was discovered by archaeologists in the Nile Valley in 1914.

The Greek Magical Papyri is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt, written mostly in ancient Greek, which each contain a number of magical spells, formulae, hymns, and rituals. The materials in the papyri date from the 100s BCE to the 400s CE. The manuscripts came to light through the antiquities trade, from the 1700s onward. One of the best known of these texts is the Mithras Liturgy.

An epikleros was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In Sparta, they were called patrouchoi (πατροῦχοι), as they were in Gortyn. Athenian women were not allowed to hold property in their own name; in order to keep her father's property in the family, an epikleros was required to marry her father's nearest male relative. Even if a woman was already married, evidence suggests that she was required to divorce her spouse to marry that relative. Spartan women were allowed to hold property in their own right, and so Spartan heiresses were subject to less restrictive rules. Evidence from other city-states is more fragmentary, mainly coming from the city-states of Gortyn and Rhegium.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom or Ptolemaic Empire was an Ancient Greek polity based in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Macedonian general Ptolemy I Soter, a companion of Alexander the Great, and ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC. Reigning for nearly three centuries, the Ptolemies were the longest and final dynasty of ancient Egypt, heralding a distinctly new era for religious and cultural syncretism between Greek and Egyptian culture.

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri are a group of manuscripts discovered during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by papyrologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt at an ancient rubbish dump near Oxyrhynchus in Egypt.

The High Priest of Ptah was sometimes referred to as "the Greatest of the Directors of Craftsmanship". This title refers to Ptah as the patron god of the craftsmen.

Horos son of Nechoutes was an Egyptian mercenary stationed in the military camp of Pathyris near Thebes in Upper Egypt. Many details about his life and family are known thanks to the survival of his private archive, written on papyrus, which was discovered in a jar in the early 1920s. The bulk of the papyri - more than fifty documents - was acquired by Lord Elkan Nathan Adler in 1924. They are, according, referred to as the "Adler Papyri". After Adler's death, they passed through several private collectors - being sold in 1948 to Martin Bodmer of Geneva, in 1970 to Hans P. Kraus of New York, and in 1989 to Martin Schøyen of Oslo - before they were acquired in 2012 for the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection with means provided by the Augustinus Foundation and the Carlsberg Foundation.

Apollonius was the dioiketes or chief finance minister of Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Little is known about his personal life; in ancient documents, he is called simply "Apollonius the dioiketes" without recording his home city or his father's name. But a great amount of information has survived about his public role, in the archive of papyri kept by his assistant Zenon.

The Ptolemaic cult of Alexander the Great was an imperial cult in ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period, promoted by the Ptolemaic dynasty. The core of the cult was the worship of the deified conqueror-king Alexander the Great, which eventually formed the basis for the ruler cult of the Ptolemies themselves. The head priest of the imperial cult was the chief priest in the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

Apollonia Senmothis, was a Greek-Egyptian businesswoman.

Ola El Aguizy is an Egyptian Egyptologist and Emeritus Professor at the University of Cairo. An expert in Demotic, she has published widely on the language. Since 2005, she has led excavations at Saqqara, uncovering the tombs of several notable figures connected to Ramesses II. In 2015, her colleagues presented her with a Festschrift entitled Mélanges offerts à Ola el-Aguizy.

Ptolemaeus son of Glaucias was a katochos who lived in the Temple of Astarte in the Serapeum at Memphis, Egypt for 20 years. Many details about his life and associates, such as his younger brother Apollonius, are known thanks to the survival of an extensive archive of papyri belonging to the katochoi of the temple.

The Papyrus Collection of the Austrian National Library, also known as the Rainer Collection and Vienna Papyrus Collection, is a papyrus collection of the Austrian National Library at Hofburg palace in Vienna. It contains around 180,000 objects overall. It is one of the most significant collections in papyrology, containing writings documenting 3 millennia of the history of Egypt from 1500 BCE–1500 CE: Ancient Egypt, Hellenistic Egypt, Roman Egypt, and Egypt during Muslim rule. It includes a specialist library of around 19,500 books and journals as well. The Austrian National Library preserves and restores the stored papyri and facilitates scholarly research and publication based on these ancient documents.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Vandorpe.

- ↑ Lewis, N: “Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt”, pp 88–103. Oxford University Press, 1986

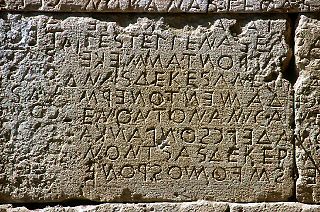

- ↑ Clarysse, Willy (2020). "Inscriptions and Papyri". The Epigraphy of Ptolemaic Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 9780198858225.

- ↑ Lewis, N: Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt, pp 88–103. Oxford University Press, 1986

- ↑ Pomeroy, S: Women in Hellenistic Egypt, pp 106. Schocken Books, 1984

- ↑ Pomeroy, S: Women in Hellenistic Egypt, pp 103–123. Schocken Books, 1984