Related Research Articles

Alboin was king of the Lombards from about 560 until 572. During his reign the Lombards ended their migrations by settling in Italy, the northern part of which Alboin conquered between 569 and 572. He had a lasting effect on Italy and the Pannonian Basin; in the former, his invasion marked the beginning of centuries of Lombard rule, and in the latter, his defeat of the Gepids and his departure from Pannonia ended the dominance there of the Germanic peoples.

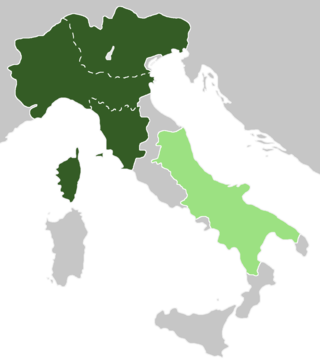

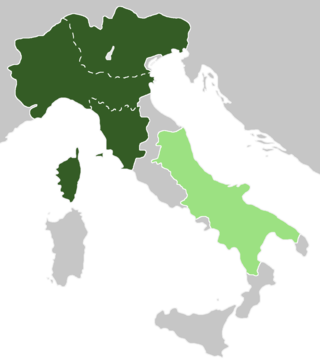

The Lombards or Longobards were a Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The Duchy of Benevento was the southernmost Lombard duchy in the Italian Peninsula that was centred on Benevento, a city in Southern Italy. Lombard dukes ruled Benevento from 571 to 1077, when it was conquered by the Normans for four years before it was given to the Pope. Being cut off from the rest of the Lombard possessions by the papal Duchy of Rome, Benevento was practically independent from the start. Only during the reigns of Grimoald and the kings from Liutprand on was the duchy closely tied to the Kingdom of the Lombards. After the fall of the kingdom in 774, the duchy became the sole Lombard territory which continued to exist as a rump state, maintaining its de facto independence for nearly 300 years, although it was divided after 849. Benevento dwindled in size in the early 11th century, and was completely captured by the Norman Robert Guiscard in 1053.

Ratchis was the Duke of Friuli (739–744) and then King of the Lombards (744–749).

The History of the Lombards or the History of the Langobards is the chief work by Paul the Deacon, written in the late 8th century. This incomplete history in six books was written after 787 and at any rate no later than 796, maybe at Montecassino.

Zotto was the military leader of the Lombards in the Mezzogiorno. He is generally considered the founder of the Duchy of Benevento in 571 and its first duke : “…Fuit autem primus Langobardorum dux in Benevento nomine Zotto, qui in ea principatus est per curricula viginti annorum…”.

Erchempert was a Benedictine monk of the Abbey of Monte Cassino in Italy in the final quarter of the ninth century. He chronicled a history of the Lombard Principality of Benevento, in the Langobardia Minor, giving an especially vivid account of the violence in southern Langobardia. Beginning with Duke Arechis II (758-787) and the Carolingian conquest of Benevento, his history, titled the Historia Langobardorum Beneventanorum degentium, stops abruptly in the winter of 888-889. Just one medieval manuscript of this text survives, from the early fourteenth century.

Langobardia Minor was the name that, in the Early Middle Ages, was given to the Lombard domains in central and southern Italy, corresponding to the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. After the conquest of the Lombard kingdom by Charlemagne in 774, it remained under Lombard control.

Ansa or Ansia was a Queen of the Lombards by marriage to Desiderius (756–774), King of the Lombards.

The Kingdom of the Lombards, also known as the Lombard Kingdom and later as the Kingdom of all Italy, was an early medieval state established by the Lombards, a Germanic people, on the Italian Peninsula in the latter part of the 6th century. The king was traditionally elected by the very highest-ranking aristocrats, the dukes, as several attempts to establish a hereditary dynasty failed. The kingdom was subdivided into a varying number of duchies, ruled by semi-autonomous dukes, which were in turn subdivided into gastaldates at the municipal level. The capital of the kingdom and the center of its political life was Pavia in the modern northern Italian region of Lombardy.

The Duchy of Friuli was a Lombard duchy in present-day Friuli, the first to be established after the conquest of the Italian peninsula in 568. It was one of the largest domains in Langobardia Major and an important buffer between the Lombard kingdom and the Slavs, Avars, and the Byzantine Empire. The original chief city in the province was Roman Aquileia, but the Lombard capital of Friuli was Forum Julii, modern Cividale.

Ferdulf or Fardulf, originally from the territories of Liguria, was the Duke of Friuli at some point between the end of the reign of Cunincpert (688-700) and the beginning of that of Aripert II (701-12). There is no evidence to associate his tenure to the year 705 alone or indeed to suggest that it was very brief.. Paul the Deacon described him as 'a man tricky and conceited' who had obtained the dukedom after the death of Duke Ado.

The Gausi or Gausian dynasty was a prominent Lombard ruling clan in the second half of the 6th century (547–572). They were either pagans or perhaps Arian Christians and were frequently at odds with the Roman Catholic Church. Under their rule, the Lombards first migrated into the Italian peninsula.

The Duchy of Tuscia, initially known as the Duchy of Lucca, was a Lombard duchy in Central Italy, which included much of today's Tuscany. After the occupation of the territories belonging to the Byzantines, the Lombards founded this flourishing duchy which, among other centres, also included Florence. The capital of the duchy was Lucca, which was located along the Via Francigena, being also the city where the duke resided.

Austria was, according to the early medieval geographical classification, the eastern portion of Langobardia Major, the north-central part of the Lombard Kingdom, extended from the Adda to Friuli and opposite to Neustria. The partition had not only been territorial, but also implied significant cultural and political differences.

Neustria was, according to the early medieval geographical classification, the western portion of Langobardia Major, the north-central part of the Lombard Kingdom, extended from the Adda (river) to the Western Alps and opposite to Austria. The partition had not only been territorial, but also implied significant cultural and political differences.

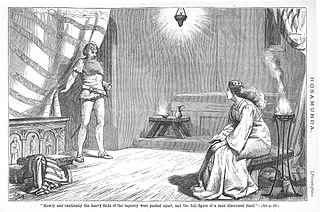

Helmichis was a Lombard noble who killed his king, Alboin, in 572 and unsuccessfully attempted to usurp his throne. Alboin's queen, Rosamund, supported or at least did not oppose Helmichis' plan to remove the king, and after the assassination Helmichis married her. The assassination was assisted by Peredeo, the king's chamber-guard, who in some sources becomes the material executer of the murder. Helmichis is first mentioned by the contemporary chronicler Marius of Avenches, but the most detailed account of his endeavours derives from Paul the Deacon's late 8th-century Historia Langobardorum.

Lombard architecture refers to the architecture of the Kingdom of the Lombards, which lasted from 568 to 774 and which was commissioned by Lombard kings and dukes.

The coinage of the Lombards refers to the autonomous productions of coins by the Lombards. It constitutes part of the coinage produced by Germanic peoples occupying the former territory of the Roman Empire during the Migration Period. All known Lombard coinage was produced after their settlement of Italy. The coinage originates from two distinct areas, in Langobardia Major between the last decades of the sixth century and 774, and in Langobardia Minor, in the duchy of Benevento, between approximately 680 and the end of the 9th century.

The Cesina family is an Italian family of Roman-Lombard origin.

References

- ↑ Rovagnati 2003 , p. 108.

- ↑ Rovagnati 2003 , p. 19.

- ↑ Lida Capo, Commento a Paolo Diacono, Storia dei Longobardi, pp. 432-433.