Related Research Articles

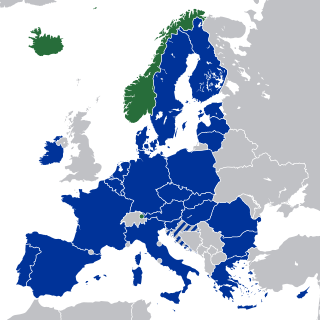

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is a regional trade organization and free trade area consisting of four European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. The organization operates in parallel with the European Union (EU), and all four member states participate in the European single market and are part of the Schengen Area. They are not, however, party to the European Union Customs Union.

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the Agreement on the European Economic Area, an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). The EEA links the EU member states and three of the four EFTA states into an internal market governed by the same basic rules. These rules aim to enable free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital within the European single market, including the freedom to choose residence in any country within this area. The EEA was established on 1 January 1994 upon entry into force of the EEA Agreement. The contracting parties are the EU, its member states, and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. New members of EFTA would not automatically become party to the EEA Agreement, as each EFTA State decides on its own whether it applies to be party to the EEA Agreement or not. According to Article 128 of the EEA Agreement, "any European State becoming a member of the Community shall, and the Swiss Confederation or any European State becoming a member of EFTA may, apply to become a party to this Agreement. It shall address its application to the EEA Council." EFTA does not envisage political integration. It does not issue legislation, nor does it establish a customs union. Schengen is not a part of the EEA Agreement. However, all of the four EFTA States participate in Schengen and Dublin through bilateral agreements. They all apply the provisions of the relevant Acquis.

Landsbanki, also commonly known as Landsbankinn was one of the largest Icelandic commercial banks; it failed as part of the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis when its subsidiary sparked the Icesave dispute. On October 7, 2008, the Icelandic Financial Supervisory Authority took control of Landsbanki and created a new bank for all the domestic operations called Nýi Landsbanki and the bank continued to operate under the same name.

Kaupthing Bank was a major international Icelandic bank, headquartered in Reykjavík, Iceland. It was taken over by the Icelandic government during the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis and the domestic Icelandic-based operations were spun into a new bank New Kaupthing, which was subsequently renamed Arion Banki. All the non-Icelandic assets and debts remained with the now defunct Kaupthing Bank. Prior to its collapse, it also allegedly loaned money to various parties with the purpose of buying Kaupthing shares.

Deposit insurance or deposit protection is a measure implemented in many countries to protect bank depositors, in full or in part, from losses caused by a bank's inability to pay its debts when due. Deposit insurance systems are one component of a financial system safety net that promotes financial stability.

The EFTA Court is a supranational judicial body responsible for the three EFTA members who are also members of the European Economic Area (EEA): Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway.

The EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) monitors compliance with the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA) in Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway (the EEA EFTA States). ESA operates independently of the States and safeguards the rights of individuals and undertakings under the EEA Agreement, ensuring free movement, fair competition, and control of state aid.

In establishing Landsbanki, the Icelandic parliament hoped to boost monetary transactions and encourage the country's nascent industries. Following its opening on 1 July 1886, the bank's first decades of operation were restricted by its limited financial capacity; it was little more than a savings and loan society. Following the turn of the 20th century, however, Icelandic society progressed and prospered as industrialisation finally made inroads, and the bank grew and developed in parallel to the nation. In the 1920s Landsbanki became Iceland's largest bank, and was made responsible for issuing its bank notes. After the issuing of bank notes was transferred to the newly established Central Bank of Iceland in 1961, Landsbanki continued to develop as a commercial bank, expanding its branch network in the ensuing decades.

The Icesave dispute was a diplomatic dispute among Iceland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. It began after the privately owned Icelandic bank Landsbanki was placed in receivership on 7 October 2008. As Landsbanki was one of three systemically important financial institutions in Iceland to go bankrupt within a few days, the Icelandic Depositors' and Investors' Guarantee Fund had no remaining funds to make good on deposit guarantees to foreign Landsbanki depositors, who held savings in the Icesave branch of the bank.

The Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) is the UK's statutory compensation scheme for customers of UK authorised financial services firms. This means it can step in to pay compensation if a firm is unable, or likely to be unable, to pay claims against it. Compensation can be in any form and by any method it determines is appropriate. It is an operationally independent body, set up under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and funded by a levy on authorised financial services firms.

The Icelandic financial crisis was a major economic and political event in Iceland between 2008 and 2010. It involved the default of all three of the country's major privately owned commercial banks in late 2008, following problems in refinancing their short-term debt and a run on deposits in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Relative to the size of its economy, Iceland's systemic banking collapse was the largest of any country in economic history. The crisis led to a severe recession and the 2009 Icelandic financial crisis protests.

The Depositors' and Investors' Guarantee Fund is the statutory deposit insurance scheme in Iceland. It is established under Act No. 98/1999 on Deposit Guarantees and Investor-Compensation Scheme, which transposes European Union directives 94/19/EC and 97/9/EC into Icelandic law, in accordance with the decisions of the European Economic Area.

The Landsbanki Freezing Order 2008 is an Order of HM Treasury to freeze the assets of Icelandic bank Landsbanki in the United Kingdom made under the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, by virtue of the fact that the Treasury reasonably believed that "action to the detriment of the United Kingdom's economy has been or is likely to be taken by a person or persons." As required by the enabling Act, the Order was approved by both Houses of Parliament on 28 October 2008, which was 20 days after the Order had come into force.

Paul v Germany [2004] ECR I-09425 is a European Court of Justice case regarding the civil liability of bank regulators in a case where those regulators were alleged to have failed in their duty. As of November 2008, it is the only ECJ case to consider the Deposit Guarantee Directive (94/19/EC), which was one of the causes of the Icesave dispute between Iceland and the United Kingdom in late 2008.

The 2010 Icelandic loan guarantees referendum, also known as the Icesave referendum, was held in Iceland on 6 March 2010.

The Norwegian Banks' Guarantee Fund administers the deposit guarantee, which guarantees deposits in Norwegian banks. The Norwegian Banks' Guarantee Fund is regulated by the Act on the Norwegian Banks’ Guarantee Fund of 23 March 2018 and the Financial Institutions Act of 10 April 2015, Chapter 19 and Chapter 20. The fund was established on 1 July 2004 following a merger of the Commercial Banks' Guarantee Fund and the Savings Banks' Guarantee Fund. The Savings Banks' Guarantee Fund has a history dating back to 1921, when the guarantee scheme was a voluntary scheme.

A referendum on the repayment of loan guarantees by Iceland to the governments of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands over the failure of the Icesave bank was held in Iceland on 9 April 2011. This was the second referendum on the issue after a previous one was held in March 2010. After the referendum failed to pass, the British and Dutch governments said that they would take the case to the European courts.

Nemea Bank was a pan-European direct bank incorporated in Malta, providing banking and investment services to individuals, businesses, institutions and high net worth individuals based in the 31 countries of the European Economic Area (EEA). The bank is currently under administration and its license was withdrawn by the ECB on the 23rd March 2017.

The United Kingdom (UK) was a member of the European Economic Area (EEA) from 1 January 1994 to 31 December 2020, following the coming into force of the 1992 EEA Agreement. Membership of the EEA is a consequence of membership of the European Union (EU). The UK ceased to be a Contracting Party to the EEA Agreement after its withdrawal from the EU on 31 January 2020, as it was a member of the EEA by virtue of its EU membership, but retained EEA rights during the Brexit transition period, based on Article 126 of the withdrawal agreement between the EU and the UK. During the transition period, which ended on 31 December 2020, the UK and EU negotiated their future relationship.

Passports of the EFTA member states are passports issued by the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member states Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. EFTA is in this article used as a common name for these countries.

References

- ↑ "Case E-16/11 - EFTA Surveillance Authority v Iceland". EFTA Court. 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "Directive 94/19/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 1994 on deposit-guarantee schemes". Eur-Lex. 1994-05-30. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "Action brought on 15 December 2011 by the EFTA Surveillance Authority against Iceland" (PDF). EFTA Court. 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "Agreement on the European Economic Area" (PDF). EFTA. 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "In the EFTA Court Case E-16/11" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Iceland. 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "In the EFTA Court Reply" (PDF). EFTA Surveillance Authority. 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ Reply

- ↑ Rejoinder

- ↑ Written observations by the Government of Norway

- ↑ "EFTA Court Judge Possibly Unfit to Rule on Icesave". Iceland Review. 23 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Directive 94/19/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 1994 on deposit-guarantee schemes". Eur-Lex. 1994-05-30. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "Agreement on the European Economic Area" (PDF). EFTA. 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2012-06-30.