Related Research Articles

William I was king of the Netherlands and grand duke of Luxembourg from 1815 until his abdication in 1840.

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Participants were representatives of all European powers and other stakeholders, chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September 1814 to June 1815.

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed between 1815 and 1830. The United Netherlands was created in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars through the fusion of territories that had belonged to the former Dutch Republic, Austrian Netherlands, and Prince-Bishopric of Liège in order to form a buffer state between the major European powers. The polity was a constitutional monarchy, ruled by William I of the House of Orange-Nassau.

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, officially the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, and commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands and the first independent Dutch state. The republic was established after seven Dutch provinces in the Spanish Netherlands revolted against Spanish rule, forming a mutual alliance against Spain in 1579 and declaring their independence in 1581. It comprised Groningen, Frisia, Overijssel, Guelders, Utrecht, Holland and Zeeland.

The Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is one of two fundamental documents governing the Kingdom of the Netherlands as well as the fundamental law of the European territory of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It is generally seen as directly derived from the one issued in 1815, constituting a constitutional monarchy; it is the third oldest constitution still in use worldwide.

The House of Orange-Nassau is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe, particularly since William the Silent organised the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule, which after the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) led to an independent Dutch state. William III of Orange led the resistance of the Netherlands and Europe to Louis XIV of France, and orchestrated the Glorious Revolution in England that established parliamentary rule. Similarly, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands was instrumental in the Dutch resistance during World War II.

In the Netherlands, the Constitution refers to Amsterdam as the capital city. However, the States General and the Executive Branch, along with the Supreme Court and the Council of State, have been situated since 1588 in The Hague as the seat of government. Since the 1983 revision of the Constitution of the Netherlands, Article 32 mentions that "the King shall be sworn in and inaugurated as soon as possible in the capital city, Amsterdam". It is the only reference in the document stating that Amsterdam is the capital. In contrast, The Hague is customarily called the residentie ("residence").

The Belgian Revolution was the conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

The Council of State is a constitutionally established advisory body in the Netherlands to the government and States General that officially consists of members of the royal family and Crown-appointed members generally having political, commercial, diplomatic or military experience. It was founded in 1531, making it one of the world's oldest still-functioning state organisations.

Gijsbert Karel, Count van Hogendorp was a liberal conservative and liberal Dutch statesman. He was the brother of Dirk van Hogendorp the elder and the father of Dirk van Hogendorp the younger.

The Historic composition of the House of Representatives of the Netherlands gives an overview of the composition of the House of Representatives of the Dutch parliament. It shows the composition after elections, splits from parties are not included.

The Treaty of Fontainebleau was an agreement concluded in Fontainebleau, France, on 11 April 1814 between Napoleon and representatives of Austria, Russia and Prussia. The treaty was signed in Paris on 11 April by the plenipotentiaries of both sides and ratified by Napoleon on 13 April. With this treaty, the allies ended Napoleon's rule as emperor of the French and sent him into exile on Elba.

The Kingdom of the Netherlands, commonly known simply as the Netherlands, is a sovereign state consisting of a collection of constituent territories united under the monarch of the Netherlands, who functions as head of state. The realm is not a federation; it is a unitary monarchy with its largest subdivision, the eponymous Netherlands, predominantly located in Western Europe and with several smaller island territories located in the Caribbean.

Marquess of Heusden is a high-ranking Dutch title of nobility retained by the Earl of Clancarty.

William II was King of the Netherlands, Grand Duke of Luxembourg, and Duke of Limburg.

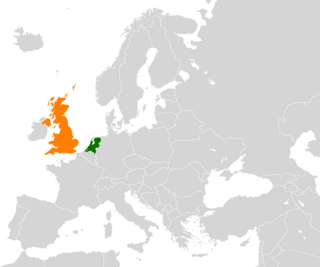

The Netherlands and the United Kingdom have a strong political and economic partnership.

The Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands was a short-lived sovereign principality and the precursor of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in which it was reunited with the Southern Netherlands in 1815. The principality was proclaimed in 1813 when the victors of the Napoleonic Wars established a political reorganisation of Europe, which would eventually be defined by the Congress of Vienna.

The Committee of United Belgians and Liégeois or United Committee of Both Nations was a political committee in Revolutionary France which brought together leaders of the failed Brabant and Liège Revolutions (1789–1791) who sought to create an independent republic in Belgium.

The Provisional Government of Belgium or the General Government of Belgium governed the Southern Netherlands from February 1814 to September 1815, when the Southern Netherlands was definitively incorporated into the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. The official documents at that time are in French, in which it was labeled as 'Gouvernement Général de la Belgique' or in German as 'Generalgouvernement von Belgien'. In Dutch it was described as 'Algemeen Bestuur der Nederlanden'.

Alexandre Charles Joseph Ghislain Count d'Aubremé was a Southern Netherlands general in the service consecutively of the First French Republic, the Batavian Republic, the Kingdom of Holland, the First French Empire, the Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands, and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. He commanded the 2nd brigade of the 3rd Netherlands division at the Battle of Waterloo. He served as Minister of War under king William I of the Netherlands.

References

- ↑ This title included the word "sovereign", to settle the old question of who would hold sovereignty. In the old Republic the States-General of the Netherlands had been sovereign, as attempts to confer sovereignty on foreign princes had been unsuccessful after the Act of Abjuration in 1581. The Orangist party had always wanted to confer sovereignty on the Prince of Orange, but this had never happened under the old Republic.

- ↑ Colenbrander, p. LXX

- ↑ Colenbrander, p. LXX, fn. 1

- ↑ The Constitution of the Netherlands of 29 March 1814

- ↑ Edward et al., pp. 519-520

- ↑ Colenbrander, p. LXII

- ↑ Edward et al., p. 520

- ↑ Godert van der Capellen

- ↑ Edward et al., pp. 522-524