Utagawa Kunisada, also known as Utagawa Toyokuni III, was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist. He is considered the most popular, prolific and commercially successful designer of ukiyo-e woodblock prints in 19th-century Japan. In his own time, his reputation far exceeded that of his contemporaries, Hokusai, Hiroshige and Kuniyoshi.

Utagawa Toyokuni, also often referred to as Toyokuni I, to distinguish him from the members of his school who took over his gō (art-name) after he died, was a great master of ukiyo-e, known in particular for his kabuki actor prints. He was the second head of the renowned Utagawa school of Japanese woodblock artists, and was the artist who elevated it to the position of great fame and power it occupied for the rest of the nineteenth century.

The Utagawa school (歌川派) was one of the main schools of ukiyo-e, founded by Utagawa Toyoharu. It was the largest ukiyo-e school of its period. The main styles were bijin-ga and uki-e. His pupil, Toyokuni I, took over after Toyoharu's death and led the group to become the most famous and powerful woodblock print school for the remainder of the 19th century.

Utagawa Hiroshige, born Andō Tokutarō, was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition.

Utagawa Kunimasa was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist of the Utagawa school. He was originally from Aizu in Iwashiro Province and first worked in a dye shop after arriving in Edo. It was there that he was noticed by Utagawa Toyokuni, to whom he became apprenticed.

Utagawa Toyohiro, birth name Okajima Tōjiro (1773–1828), was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist and painter. He was a member of the Utagawa school and studied under Utagawa Toyoharu, the school's founder. His works include a number of ukiyo-e landscape series, as well as many depictions of the daily activities in the Yoshiwara entertainment quarter; many of his stylistic features paved the way for Hokusai and Hiroshige, as well as producing an important series of ukiyo-e triptychs in collaboration with Toyokuni, and numerous book and e-hon illustrations, which occupied him in his later years.

Utagawa Kunimasu was a designer of ukiyo-e woodblock prints in Osaka who was active during the late Edo period. He was a leading producer of kamigata-e, prints from the Osaka and Kyoto areas. He is also known as Sadamasu [貞升], the artist name he used prior to Kunimasu.

Utagawa Toyoharu was a Japanese artist in the ukiyo-e genre, known as the founder of the Utagawa school and for his uki-e pictures that incorporated Western-style geometrical perspective to create a sense of depth.

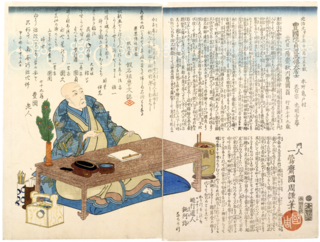

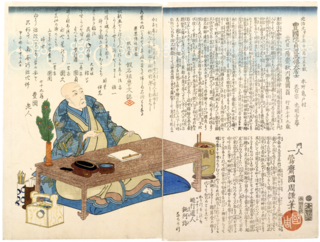

Shini-e, also called "death pictures" or "death portraits", are Japanese woodblock prints, particularly those done in the ukiyo-e style popular through the Edo period (1603–1867) and into the beginnings of the 20th century.

E-hon is the Japanese term for picture books. It may be applied in the general sense, or may refer specifically to a type of woodblock printed illustrated volume published in the Edo period (1603–1867).

Female Ghost is an ukiyo-e woodblock print dating to 1852 by celebrated Edo period artist Utagawa Kunisada, also known as Toyokuni III. Female Ghost exemplifies the nineteenth century Japanese vogue for the supernatural and superstitious in the literary and visual arts. The print is part of the permanent collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Fan print with two bugaku dancers is an ukiyo-e woodblock print dating to sometime between the mid 1820s and 1844 by celebrated Edo period artist Utagawa Kunisada, also known as Toyokuni III. This print is simultaneously an example of the uchiwa-e and aizuri-e genres. It is part of the permanent collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

The two ukiyo-e woodblock prints making up View of Tempōzan Park in Naniwa are half of a tetraptych by Osaka artist Gochōtei Sadamasu. They depict a scene of crowds visiting Mount Tempō in springtime to admire its natural beauty. The sheets belong to the permanent collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada.

Ichikawa Omezō as a Pilgrim and Ichikawa Yaozō as a Samurai is an ukiyo-e woodblock print dating to around 1801 by Edo period artist Utagawa Toyokuni I. Featuring two of the most prominent actors of the day as characters in a contemporary kabuki drama, it is a classic example of the kabuki-e or yakusha-e genre. The print is part of the permanent collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Bust portrait of Actor Kataoka Ichizō I is an ukiyo-e woodblock print belonging to the permanent collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada. The print dates to around the mid nineteenth century, and is an example of kamigata-e, prints produced in the Osaka and Kyoto areas. The ROM attributes the print to Utagawa Sadamasu II, but other institutions identify Utagawa Kunimasu—also known as Sadamasu I—as the artist.

Three Travellers before a Waterfall is an ukiyo-e woodblock print by Osaka-based late Edo period print designer Ryūsai Shigeharu (1802–1853). It depicts a light-hearted scene of two men and one woman travelling on foot through the country-side. The print belongs to the permanent collection of the Prince Takamado Gallery of Japanese Art in the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada.

Actor Nakamura Shikan II as Satake Shinjūrō is an ukiyo-e woodblock print by Osaka-based late Edo period print designer Shungyōsai Hokusei. It depicts celebrated kabuki actor Nakamura Shikan II as a character in the play Keisei Asoyama Sakura. The print belongs to the permanent collection of the Prince Takamado Gallery of Japanese Art in the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada.

Actor Ichikawa Shikō as Katō Yomoshichi from the series Tales of Retainers of Unswerving Loyalty is an ukiyo-e woodblock print by Osaka-based late Edo period print designer Gosōtei Hirosada (五粽亭廣貞). Each of the three sheets contains a different version of the same image, reflecting progressive stages in the woodblock printing process. The print is a portrait of a contemporary kabuki actor in the role of a samurai, and belongs to a series of images of heroes. The print belongs to the permanent collection of the Prince Takamado Gallery of Japanese Art in the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada.

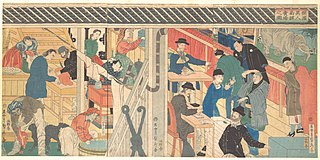

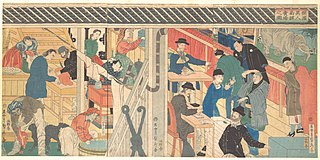

Utagawa Sadahide, also known as Gountei Sadahide, was a Japanese artist best known for his prints in the ukiyo-e style as a member of the Utagawa school. His prints covered a wide variety of genres; amongst his best known are his Yokohama-e pictures of foreigners in Yokohama in the 1860s, a period when he was a best-selling artist. He was a member of the Tokugawa shogunate's delegation to the International Exposition of 1867 in Paris.

Nishimuraya Yohachi was one of the leading publishers of woodblock prints in late 18th Japan. He founded the Nishimuraya Yohachi publishing house, also known as Nishiyo (西与), which operated in Nihonbashi's Bakurochō Nichōme under the shop name Eijudō. The firm's exact dates are unclear, but many art historians date its activity to between c. 1751 and 1860.