In physics, the cross section is a measure of the probability that a specific process will take place when some kind of radiant excitation intersects a localized phenomenon. For example, the Rutherford cross-section is a measure of probability that an alpha particle will be deflected by a given angle during a collision with an atomic nucleus. Cross section is typically denoted σ (sigma) and is expressed in units of area, more specific in barns. In a way, it can be thought of as the size of the object that the excitation must hit in order for the process to occur, but more exactly, it is a parameter of a stochastic process.

In mathematics, the Dirac delta function, also known as the unit impulse symbol, is a generalized function or distribution over the real numbers, whose value is zero everywhere except at zero, and whose integral over the entire real line is equal to one.

Noether's theorem or Noether's first theorem states that every differentiable symmetry of the action of a physical system with conservative forces has a corresponding conservation law. The theorem was proven by mathematician Emmy Noether in 1915 and published in 1918, after a special case was proven by E. Cosserat and F. Cosserat in 1909. The action of a physical system is the integral over time of a Lagrangian function, from which the system's behavior can be determined by the principle of least action. This theorem only applies to continuous and smooth symmetries over physical space.

Synchrotron radiation is the electromagnetic radiation emitted when charged particles are accelerated radially, e.g., when they are subject to an acceleration perpendicular to their velocity. It is produced, for example, in synchrotrons using bending magnets, undulators and/or wigglers. If the particle is non-relativistic, the emission is called cyclotron emission. If the particles are relativistic, sometimes referred to as ultrarelativistic, the emission is called synchrotron emission. Synchrotron radiation may be achieved artificially in synchrotrons or storage rings, or naturally by fast electrons moving through magnetic fields. The radiation produced in this way has a characteristic polarization and the frequencies generated can range over the entire electromagnetic spectrum, which is also called continuum radiation.

In physics, screening is the damping of electric fields caused by the presence of mobile charge carriers. It is an important part of the behavior of charge-carrying fluids, such as ionized gases, electrolytes, and charge carriers in electronic conductors . In a fluid, with a given permittivity ε, composed of electrically charged constituent particles, each pair of particles interact through the Coulomb force as

In vector calculus, Green's theorem relates a line integral around a simple closed curve C to a double integral over the plane region D bounded by C. It is the two-dimensional special case of Stokes' theorem.

Linear elasticity is a mathematical model of how solid objects deform and become internally stressed due to prescribed loading conditions. It is a simplification of the more general nonlinear theory of elasticity and a branch of continuum mechanics.

In the calculus of variations, a field of mathematical analysis, the functional derivative relates a change in a Functional to a change in a function on which the functional depends.

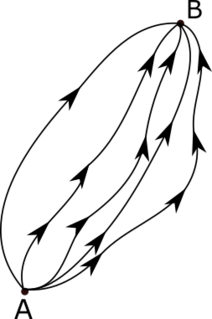

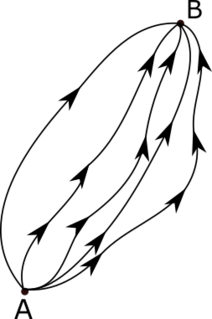

The path integral formulation is a description in quantum mechanics that generalizes the action principle of classical mechanics. It replaces the classical notion of a single, unique classical trajectory for a system with a sum, or functional integral, over an infinity of quantum-mechanically possible trajectories to compute a quantum amplitude.

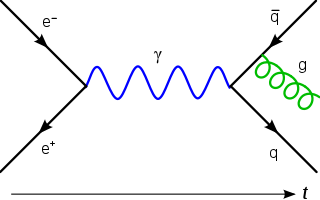

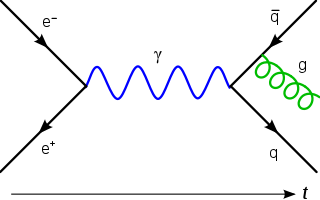

In quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, the propagator is a function that specifies the probability amplitude for a particle to travel from one place to another in a given period of time, or to travel with a certain energy and momentum. In Feynman diagrams, which serve to calculate the rate of collisions in quantum field theory, virtual particles contribute their propagator to the rate of the scattering event described by the respective diagram. These may also be viewed as the inverse of the wave operator appropriate to the particle, and are, therefore, often called (causal) Green's functions.

In physics, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, named after William Rowan Hamilton and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, is an alternative formulation of classical mechanics, equivalent to other formulations such as Newton's laws of motion, Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics. The Hamilton–Jacobi equation is particularly useful in identifying conserved quantities for mechanical systems, which may be possible even when the mechanical problem itself cannot be solved completely.

In mechanics, virtual work arises in the application of the principle of least action to the study of forces and movement of a mechanical system. The work of a force acting on a particle as it moves along a displacement is different for different displacements. Among all the possible displacements that a particle may follow, called virtual displacements, one will minimize the action. This displacement is therefore the displacement followed by the particle according to the principle of least action. The work of a force on a particle along a virtual displacement is known as the virtual work.

Electric potential energy, is a potential energy that results from conservative Coulomb forces and is associated with the configuration of a particular set of point charges within a defined system. An object may have electric potential energy by virtue of two key elements: its own electric charge and its relative position to other electrically charged objects.

In mathematics, in particular in algebraic geometry and differential geometry, Dolbeault cohomology is an analog of de Rham cohomology for complex manifolds. Let M be a complex manifold. Then the Dolbeault cohomology groups depend on a pair of integers p and q and are realized as a subquotient of the space of complex differential forms of degree (p,q).

The Frank–Tamm formula yields the amount of Cherenkov radiation emitted on a given frequency as a charged particle moves through a medium at superluminal velocity. It is named for Russian physicists Ilya Frank and Igor Tamm who developed the theory of the Cherenkov effect in 1937, for which they were awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1958.

Defect types include atom vacancies, adatoms, steps, and kinks that occur most frequently at surfaces due to the finite material size causing crystal discontinuity. What all types of defects have in common, whether surface or bulk defects, is that they produce dangling bonds that have specific electron energy levels different from those of the bulk. This difference occurs because these states cannot be described with periodic Bloch waves due to the change in electron potential energy caused by the missing ion cores just outside the surface. Hence, these are localized states that require separate solutions to the Schrödinger equation so that electron energies can be properly described. The break in periodicity results in a decrease in conductivity due to defect scattering.

The electron-LA phonon interaction is an interaction that can take place between an electron and a longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonon in a material such as a semiconductor.

Multipole radiation is a theoretical framework for the description of electromagnetic or gravitational radiation from time-dependent distributions of distant sources. These tools are applied to physical phenomena which occur at a variety of length scales - from gravitational waves due to galaxy collisions to gamma radiation resulting from nuclear decay. Multipole radiation is analyzed using similar multipole expansion techniques that describe fields from static sources, however there are important differences in the details of the analysis because multipole radiation fields behave quite differently from static fields. This article is primarily concerned with electromagnetic multipole radiation, although the treatment of gravitational waves is similar.

In mathematics, the Neumann–Poincaré operator or Poincaré–Neumann operator, named after Carl Neumann and Henri Poincaré, is a non-self-adjoint compact operator introduced by Poincaré to solve boundary value problems for the Laplacian on bounded domains in Euclidean space. Within the language of potential theory it reduces the partial differential equation to an integral equation on the boundary to which the theory of Fredholm operators can be applied. The theory is particularly simple in two dimensions—the case treated in detail in this article—where it is related to complex function theory, the conjugate Beurling transform or complex Hilbert transform and the Fredholm eigenvalues of bounded planar domains.

Phase reduction is a method used to reduce a multi-dimensional dynamical equation describing a nonlinear limit cycle oscillator into a one-dimensional phase equation. Many phenomena in our world such as chemical reactions, electric circuits, mechanical vibrations, cardiac cells, and spiking neurons are examples of rhythmic phenomena, and can be considered as nonlinear limit cycle oscillators.