Related Research Articles

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

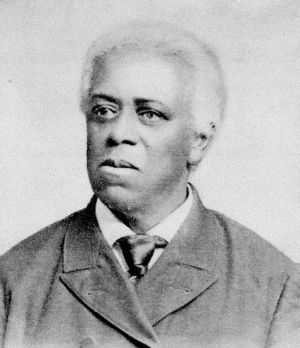

Lewis Hayden escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and reached Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an abolitionist, lecturer, businessman, and politician. Before the American Civil War, he and his wife Harriet Hayden aided numerous fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, often sheltering them at their house.

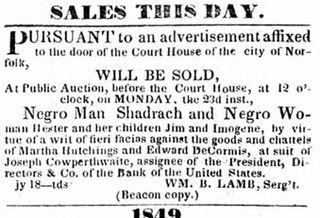

Shadrach Minkins was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins. He is known for being freed from a courtroom in Boston after being captured by United States marshals under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Members of the Boston Vigilance Committee freed and hid him, helping him get to Canada via the Underground Railroad. Minkins settled in Montreal, where he raised a family. Two men were prosecuted in Boston for helping free him, but they were acquitted by the jury.

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an abolitionist organization formed in Boston, Massachusetts, to protect escaped slaves from being kidnapped and returned to slavery in the South. The Committee aided hundreds of escapees, most of whom arrived as stowaways on coastal trading vessels and stayed a short time before moving on to Canada or England. Notably, members of the Committee provided legal and other aid to George Latimer, Ellen and William Craft, Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns.

William Cooper Nell was an American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Writing for abolitionist newspapers The Liberator and The North Star, he helped publicize the anti-slavery cause. He published the North Star from 1847 to 1851, moving temporarily to Rochester, New York.

The William C. Nell House, now a private residence, was a boarding home located in 3 Smith Court in the Beacon Hill neighbourhood of Boston, Massachusetts, opposite the former African Meeting House, now the Museum of African American History.

The Frances H. and Jonathan Drake House is an historic house at 21 Franklin Street in Leominster, Massachusetts, United States. Built in 1848, this typical Greek Revival worker's cottage is notable as a stop on the Underground Railroad during the pre-Civil War years. Frances and Jonathan Drake are documented as having hosted Shadrach Minkins after he was successfully extracted from custody at a Boston court hearing. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.

Robert Morris was one of the first African-American attorneys in the United States, and was called "the first really successful colored lawyer in America."

George Washington Latimer was an escaped slave whose case became a major political issue in Massachusetts.

Edward Garrison Walker (1830–1901), also Edwin Garrison Walker, was an American artisan in Boston who became an attorney; in 1861, he became one of the first black men to pass the Massachusetts bar. In 1866 he and Charles Lewis Mitchell were the first two African Americans elected to the Massachusetts state legislature. Walker was the son of Eliza and David Walker, the militant abolitionist and author of An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829).

John James Smith was a barber shop owner, abolitionist, a three-term Massachusetts state representative, and one of the first African-American members of the Boston Common Council. A Republican, he served three terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He was born in Richmond Virginia. He took part in the California Gold Rush.

Lewis and Harriet Hayden House was the home of African-American abolitionists who had escaped from slavery in Kentucky; it is located in Beacon Hill, Boston. They maintained the home as a stop on the Underground Railroad, and the Haydens were visited by Harriet Beecher Stowe as research for her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). Lewis Hayden was an important leader in the African-American community of Boston; in addition, he lectured as an abolitionist and was a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee, which resisted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Nathaniel Booth was an African American who escaped from slavery.

Samuel Edmund Sewall (1799–1888) was an American lawyer, abolitionist, and suffragist. He co-founded the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, lent his legal expertise to the Underground Railroad, and served a term in the Massachusetts Senate as a Free-Soiler.

Austin Bearse (1808-1881) was a sea captain from Cape Cod who provided transportation for fugitive slaves in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

The New England Freedom Association was an organization founded by African Americans in Boston for the purpose of assisting fugitive slaves.

The Massasoit Guards were an African-American militia company active in 1850s Boston. Clothing retailer John P. Coburn founded the group to police Beacon Hill and protect residents from slave catchers. Attorney Robert Morris repeatedly petitioned the Massachusetts legislature on their behalf, but the Massasoit Guards were never officially recognized or supported by the state. The group was a precursor to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.

Ellis Gray Loring was an American attorney, abolitionist, and philanthropist from Boston. He co-founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society, provided legal advice to abolitionists, harbored fugitive slaves in his home, and helped finance the abolitionist newspaper, the Liberator. Loring also mentored Robert Morris, who went on to become one of the first African-American attorneys in the United States.

John P. Coburn (1811–1873) was a 19th-century African-American abolitionist, civil rights activist, tailor and clothier from Boston, Massachusetts. For most of his life, he resided at 2 Phillips Street in Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood. Coburn was one of the wealthiest African Americans in Boston of his time. His property on the North Slope of Beacon Hill had the third highest real property value in an 1850 census. Coburn was heavily involved in abolition-related work within his community, specifically work related to the New England Freedom Association and the Massasoit Guards.

Harriet Bell Hayden was an African-American antislavery activist in Boston, Massachusetts. She and her husband, Lewis Hayden, escaped slavery in Kentucky and became the primary operators of the Underground Railroad in Boston. They aided the John Brown slave revolt conspiracy, and she played a leadership role in Boston's Black community in the decades following the U.S. Civil War.

References

- ↑ "Presentation and Farewell Meeting". The Liberator. Vol. 19, no. 30. 27 July 1849. p. 118.

- ↑ "Presentation and Farewell Meeting". The Liberator. Vol. 19, no. 28. 13 July 1849. p. 110.

- ↑ Ward, Jean M. (2022). "George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)". Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Miscellany: First Charge". The Liberator. Vol. 14, no. 46. 15 Nov 1844. p. 184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grover, Kathryn; da Silva, Janine (2002). Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site. National Park Service. OCLC 424500372.

- 1 2 "Riley, Elizabeth (1791-1855) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". blackpast.org. 14 January 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ↑ Collison, Gary (1997). Shadrach Minkins: From Fugitive Slave to Citizen . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-80298-8.

- ↑ Siebert, Wilbur (September 1936). "The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts". The New England Quarterly. 9 (3): 447–467. doi:10.2307/360280. JSTOR 360280.

- ↑ "All Sorts of Paragraphs". Boston Post. 30 Jan 1852. p. 2.

- 1 2 "Died-- In Boston". The Liberator. Vol. 25, no. 6. 9 Feb 1855. p. 23.