The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment, organized in the Northern states during the Civil War. Authorized by the Emancipation Proclamation, the regiment consisted of African-American enlisted men commanded by white officers.

Beacon Hill is a historic neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, and the hill upon which the Massachusetts State House resides. The term "Beacon Hill" is used locally as a metonym to refer to the state government or the legislature itself, much like Washington, D.C.'s Capitol Hill does at the federal level.

The African Meeting House, also known variously as First African Baptist Church, First Independent Baptist Church and the Belknap Street Church, was built in 1806 and is now the oldest black church edifice still standing in the United States. The church also established a school, at first holding classes in its basement. After serving most of the nineteenth century as a church, it then served as a synagogue until 1972 when it was purchased for the Museum of African American History. It is located in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, adjacent to the historically Black American Abiel Smith School, now also part of the museum. It is a National Historic Landmark.

The Charles Street Meeting House is an early-nineteenth-century historic church in Beacon Hill at 70 Charles Street, Boston, Massachusetts.

Abiel Smith School, founded in 1835, is a school located at 46 Joy Street in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, adjacent to the African Meeting House. It is named for Abiel Smith, a white philanthropist who left money in his will to the city of Boston for the education of black children.

Lewis Hayden escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and reached Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an abolitionist, lecturer, businessman, and politician. Before the American Civil War, he and his wife Harriet Hayden aided numerous fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, often sheltering them at their house.

William Cooper Nell was an American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Writing for abolitionist newspapers The Liberator and The North Star, he helped publicize the anti-slavery cause. He published the North Star from 1847 to 18xx, moving temporarily to Rochester, New York.

The William C. Nell House, now a private residence, was a boarding home located in 3 Smith Court in the Beacon Hill neighbourhood of Boston, Massachusetts, opposite the former African Meeting House, now the Museum of African American History.

Robert Morris was one of the first African-American attorneys in the United States, and was called "the first really successful colored lawyer in America."

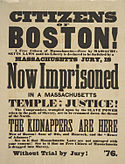

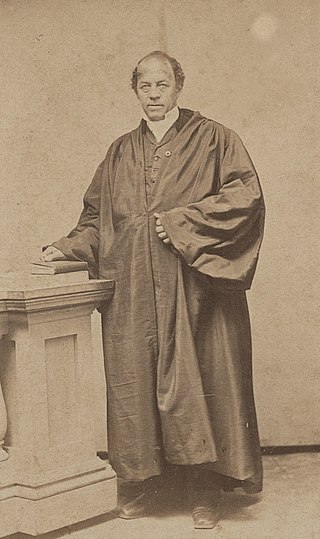

Leonard Andrew Grimes was an African-American abolitionist and pastor. He served as a conductor of the Underground Railroad, including his efforts to free fugitive slave Anthony Burns captured in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. After the Civil War began, Grimes petitioned for African-American enlistment. He then recruited soldiers for the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

John J. Smith House was the home of John J. Smith from 1878 to 1893. Smith was an African American abolitionist, Underground Railroad contributor and politician, including three terms as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He also played a key role in rescuing Shadrach Minkins from federal custody, along with Lewis Hayden and others.

John James Smith was a barber shop owner, abolitionist, a three-term Massachusetts state representative, and one of the first African-American members of the Boston Common Council. A Republican, he served three terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He was born in Richmond Virginia. He took part in the California Gold Rush.

The John Coburn House was the home of John P. Coburn (1811–1873), an African-American abolitionist who aided people on the Underground Railroad. The home is currently a private residence. It is on the Black Heritage Trail and its history is included in walking tours by the Boston African American National Historic Site.

The Phillips School was a 19th-century school located in Beacon Hill, Boston, Massachusetts. It is now a private residence. It is on the Black Heritage Trail and its history is included in walking tours by the Boston African American National Historic Site. Built in 1824, it was a school for white children. After Massachusetts law from 1855 required school desegregation, Phillips was one of the first integrated schools in Boston.

Lewis and Harriet Hayden House was the home of African-American abolitionists who had escaped from slavery in Kentucky; it is located in Beacon Hill, Boston. They maintained the home as a stop on the Underground Railroad, and the Haydens were visited by Harriet Beecher Stowe as research for her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). Lewis Hayden was an important leader in the African-American community of Boston; in addition, he lectured as an abolitionist and was a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee, which resisted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The Boston Women's Heritage Trail is a series of walking tours in Boston, Massachusetts, leading past sites important to Boston women's history. The tours wind through several neighborhoods, including the Back Bay and Beacon Hill, commemorating women such as Abigail Adams, Amelia Earhart, and Phillis Wheatley. The guidebook includes seven walks and introduces more than 200 Boston women.

Until 1950, African Americans were a small but historically important minority in Boston, where the population was majority white. Since then, Boston's demographics have changed due to factors such as immigration, white flight, and gentrification. According to census information for 2010–2014, an estimated 180,657 people in Boston are Black/African American, either alone or in combination with another race. Despite being in the minority, and despite having faced housing, educational, and other discrimination, African Americans in Boston have made significant contributions in the arts, politics, and business since colonial times.

John P. Coburn (1811–1873) was a 19th-century African-American abolitionist, civil rights activist, tailor and clothier from Boston, Massachusetts. For most of his life, he resided at 2 Phillips Street in Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood. Coburn was one of the wealthiest African Americans in Boston of his time. His property on the North Slope of Beacon Hill had the third highest real property value in an 1850 census. Coburn was heavily involved in abolition-related work within his community, specifically work related to the New England Freedom Association and the Massasoit Guards.

Elizabeth Cook Riley was an African-American Bostonian abolitionist who aided in the escape of fugitive slave Shadrach Minkins. She was a member of the committee which raised the first funds towards William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator, a prominent antislavery newspaper. Afterwards, she was active in the Boston abolitionist community, helping to organize meetings and events.