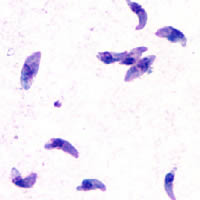

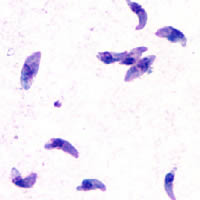

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii, an apicomplexan. Infections with toxoplasmosis are associated with a variety of neuropsychiatric and behavioral conditions. Occasionally, people may have a few weeks or months of mild, flu-like illness such as muscle aches and tender lymph nodes. In a small number of people, eye problems may develop. In those with a weak immune system, severe symptoms such as seizures and poor coordination may occur. If a woman becomes infected during pregnancy, a condition known as congenital toxoplasmosis may affect the child.

Dirofilaria immitis, also known as heartworm or dog heartworm, is a parasitic roundworm that is a type of filarial worm, a small thread-like worm, and which causes dirofilariasis. It is spread from host to host through the bites of mosquitoes. Four genera of mosquitoes transmit dirofilariasis, Aedes, Culex, Anopheles, and Mansonia. The definitive host is the dog, but it can also infect cats, wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes, ferrets, bears, seals, sea lions and, under rare circumstances, humans.

Parelaphostrongylus tenuis is a neurotropic nematode parasite common to white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus, which causes damage to the central nervous system. Moose, elk, caribou, mule deer, and others are also susceptible to the parasite, but are aberrant hosts and are infected in neurological instead of meningeal tissue. The frequency of infection in these species increases dramatically when their ranges overlap high densities of white-tailed deer.

Coccidiosis is a parasitic disease of the intestinal tract of animals caused by coccidian protozoa. The disease spreads from one animal to another by contact with infected feces or ingestion of infected tissue. Diarrhea, which may become bloody in severe cases, is the primary symptom. Most animals infected with coccidia are asymptomatic, but young or immunocompromised animals may suffer severe symptoms and death.

Neospora caninum is a coccidian parasite that was identified as a species in 1988. Prior to this, it was misclassified as Toxoplasma gondii due to structural similarities. The genome sequence of Neospora caninum has been determined by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the University of Liverpool. Neospora caninum is an important cause of spontaneous abortion in infected livestock.

Viral encephalitis is inflammation of the brain parenchyma, called encephalitis, by a virus. The different forms of viral encephalitis are called viral encephalitides. It is the most common type of encephalitis and often occurs with viral meningitis. Encephalitic viruses first cause infection and replicate outside of the central nervous system (CNS), most reaching the CNS through the circulatory system and a minority from nerve endings toward the CNS. Once in the brain, the virus and the host's inflammatory response disrupt neural function, leading to illness and complications, many of which frequently are neurological in nature, such as impaired motor skills and altered behavior.

Neurosyphilis is the infection of the central nervous system in a patient with syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics, the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been reported in HIV-infected patients. Meningitis is the most common neurological presentation in early syphilis. Tertiary syphilis symptoms are exclusively neurosyphilis, though neurosyphilis may occur at any stage of infection.

Wobbler disease is a catchall term referring to several possible malformations of the cervical vertebrae that cause an unsteady (wobbly) gait and weakness in dogs and horses. A number of different conditions of the cervical (neck) spinal column cause similar clinical signs. These conditions may include malformation of the vertebrae, intervertebral disc protrusion, and disease of the interspinal ligaments, ligamenta flava, and articular facets of the vertebrae. Wobbler disease is also known as cervical vertebral instability (CVI), cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM), and cervical vertebral malformation (CVM). In dogs, the disease is most common in large breeds, especially Great Danes and Doberman Pinschers. In horses, it is not linked to a particular breed, though it is most often seen in tall, race-bred horses of Thoroughbred or Standardbred ancestry. It is most likely inherited to at least some extent in dogs and horses.

Sarcocystis is a genus of protozoan parasites, with many species infecting mammals, reptiles and birds. Its name is dervived from Greek sarx = flesh and kystis = bladder.

Blastocystosis refers to a medical condition caused by infection with Blastocystis. Blastocystis is a protozoal, single-celled parasite that inhabits the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other animals. Many different types of Blastocystis exist, and they can infect humans, farm animals, birds, rodents, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and even cockroaches. Blastocystosis has been found to be a possible risk factor for development of irritable bowel syndrome.

Ponazuril (INN), sold by Merial, Inc., now part of Boehringer Ingelheim, under the trade name Marquis® , is a drug currently approved for the treatment of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) in horses, caused by coccidia Sarcocystis neurona. Veterinarians have been preparing a formulary version of the medication for use in small animals such as cats, dogs, and rabbits against coccidia as an intestinal parasite. Coccidia treatment in small animals is far shorter than treatment for EPM.

The central nervous system (CNS) controls most of the functions of the body and mind. It comprises the brain, spinal cord and the nerve fibers that branch off to all parts of the body. The CNS viral diseases are caused by viruses that attack the CNS. Existing and emerging viral CNS infections are major sources of human morbidity and mortality.

Neospora hughesi is an obligate protozoan apicomplexan parasite that causes myelitis and equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) in horses, and has only been documented in North America. EPM is a neurological disease from lesions in the spinal cord, brain stem, or brain from parasites such as N. hughesi or Sarcocystis neurona. Signs that a horse may have EPM include ataxia, muscle atrophy, difficulty swallowing, and head tilt. There are antiprotozoal drugs, such as the 28-day course of ponazuril, to treat the disease, as well as anti-inflammatories to alleviate neurologic symptoms

Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidial parasite of mammals with world-wide distribution. An important cause of neurologic and renal disease in rabbits, E. cuniculi can also cause disease in immunocompromised people.

Coenurosis is a parasitic infection that results when humans ingest the eggs of dog tapeworm species Taenia multiceps, T. serialis, T. brauni, or T. glomerata.

Anoplocephala perfoliata is the most common intestinal tapeworm of horses, and an agent responsible for some cases of equine colic.

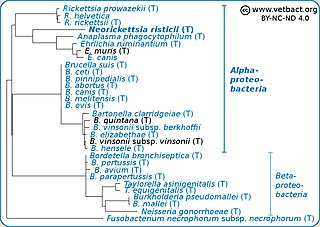

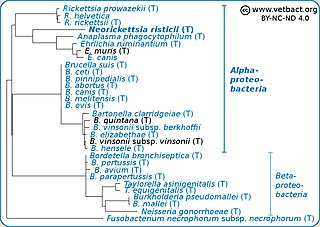

Neorickettsia risticii, formerly Ehrlichia risticii, is an obligate intracellular gram negative bacteria that typically lives as an endosymbiont in parasitic flatworms, specifically flukes. N. risticii is the known causative agent of equine neorickettsiosis, which gets its name from its discovery near the Potomac River in Maryland and Virginia. N. risticii was first recovered from horses in this region in 1984 but was not recognized as the causative agent of PHF until 1979. Potomac horse fever is currently endemic in the United States but has also been reported with lower frequency in other regions, including Canada, Brazil, Uruguay, and Europe. PHF is a condition that is clinically important for horses since it can cause serious signs such as fever, diarrhea, colic, and laminitis. PHF has a fatality rate of approximately 30%, making this condition one of the concerns for horse owners in endemic regions N. risticii is typically acquired in the middle to late summer near freshwater streams or rivers, as well as on irrigated pastures. This is a seasonal infection because it relies on the ingestion of an arthropod vector, which is more commonly found on pasture in the summer months. Although N. risticii is a well known causative agent for PHF in horses, it may act as a potential pathogen in cats and dogs as well. Not only has N. risticii been successfully cultured from monocytes of dogs and cats, but cats have become clinically ill after experimental infection with the bacteria. In addition, N. risticii has been isolated and cultured from human histiocytic lymphoma cells.

Taenia hydatigena is one of the adult forms of the canine and feline tapeworm. This infection has a worldwide geographic distribution. Humans with taeniasis can infect other humans or animal intermediate hosts by eggs and gravid proglottids passed in the feces.

Sarcocystis calchasi is an apicomplexan parasite. It has been identified to be the cause of Pigeon protozoal encephalitis (PPE) in the intermediate hosts, domestic pigeons. PPE is a central-nervous disease of domestic pigeons. Initially there have been reports of this parasite in Germany, with an outbreak in 2008 and in 2011 in the United States. Sarcocystis calchasi is transmitted by the definitive host Accipter hawks.

Sarcocystis neurona is primarily a neural parasite of horses and its management is of concern in veterinary medicine. The protozoan Sarcocystis neurona is a protozoan of single celled character and belongs to the family Sarcocystidae, in a group called coccidia. The protozoan, S. neurona, is a member of the genus Sarcocystis, and is most commonly associated with equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM). The protozoan, S. neurona, can be easily cultivated and genetically manipulated, hence its common use as a model to study numerous aspects of cell biology.