The troposphere is the first and lowest layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, and contains 75% of the total mass of the planetary atmosphere, 99% of the total mass of water vapour and aerosols, and is where most weather phenomena occur. From the planetary surface of the Earth, the average height of the troposphere is 18 km in the tropics; 17 km in the middle latitudes; and 6 km in the high latitudes of the polar regions in winter; thus the average height of the troposphere is 13 km.

The tropopause is the atmospheric boundary that demarcates the troposphere from the stratosphere; which are two of the five layers of the atmosphere of Earth. The tropopause is a thermodynamic gradient-stratification layer, that marks the end of the troposphere, and lies approximately 17 kilometres (11 mi) above the equatorial regions, and approximately 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) above the polar regions.

A sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) is an event in which the polar stratospheric temperature rises by several tens of kelvins over the course of a few days. The warming is preceded by a slowing then reversal of the westerly winds in the stratospheric polar vortex. SSWs occur about 6 times per decade in the northern hemisphere, and only about once every 20-30 years in the southern hemisphere.

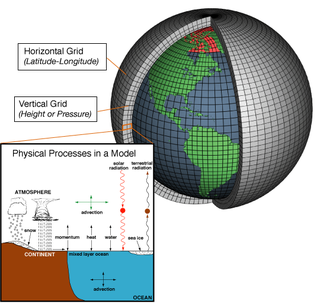

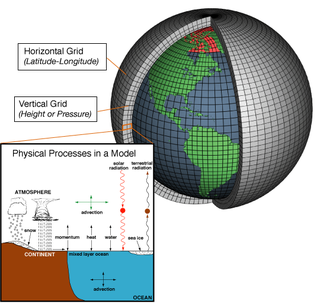

A general circulation model (GCM) is a type of climate model. It employs a mathematical model of the general circulation of a planetary atmosphere or ocean. It uses the Navier–Stokes equations on a rotating sphere with thermodynamic terms for various energy sources. These equations are the basis for computer programs used to simulate the Earth's atmosphere or oceans. Atmospheric and oceanic GCMs are key components along with sea ice and land-surface components.

Richard Siegmund Lindzen is an American atmospheric physicist known for his work in the dynamics of the middle atmosphere, atmospheric tides, and ozone photochemistry. He has published more than 200 scientific papers and books. From 1983 until his retirement in 2013, he was Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was a lead author of Chapter 7, "Physical Climate Processes and Feedbacks," of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Third Assessment Report on climate change. He has disputed the scientific consensus on climate change and criticizes what he has called "climate alarmism."

A circumpolar vortex, or simply polar vortex, is a large region of cold, rotating air that encircles both of Earth's polar regions. Polar vortices also exist on other rotating, low-obliquity planetary bodies. The term polar vortex can be used to describe two distinct phenomena; the stratospheric polar vortex, and the tropospheric polar vortex. The stratospheric and tropospheric polar vortices both rotate in the direction of the Earth's spin, but they are distinct phenomena that have different sizes, structures, seasonal cycles, and impacts on weather.

The eye is a region of mostly calm weather at the center of tropical cyclones. The eye of a storm is a roughly circular area, typically 30–65 kilometers in diameter. It is surrounded by the eyewall, a ring of towering thunderstorms where the most severe weather and highest winds occur. The cyclone's lowest barometric pressure occurs in the eye and can be as much as 15 percent lower than the pressure outside the storm.

In fluid mechanics, potential vorticity (PV) is a quantity which is proportional to the dot product of vorticity and stratification. This quantity, following a parcel of air or water, can only be changed by diabatic or frictional processes. It is a useful concept for understanding the generation of vorticity in cyclogenesis, especially along the polar front, and in analyzing flow in the ocean.

Jerry Mahlman was an American meteorologist and climatologist.

Horizontal convective rolls, also known as horizontal roll vortices or cloud streets, are long rolls of counter-rotating air that are oriented approximately parallel to the ground in the planetary boundary layer. Although horizontal convective rolls, also known as cloud streets, have been clearly seen in satellite photographs for the last 30 years, their development is poorly understood, due to a lack of observational data. From the ground, they appear as rows of cumulus or cumulus-type clouds aligned parallel to the low-level wind. Research has shown these eddies to be significant to the vertical transport of momentum, heat, moisture, and air pollutants within the boundary layer. Cloud streets are usually more or less straight; rarely, cloud streets assume paisley patterns when the wind driving the clouds encounters an obstacle. Those cloud formations are known as von Kármán vortex streets.

The Global horizontal sounding technique (GHOST) program was an atmospheric field research project in the late 1960s for investigating the technical ability to gather weather data using hundreds of simultaneous long-duration balloons for very long-range global scale numerical weather prediction in preparation for the Global Atmospheric Research Program (GARP).

Dr. André Robert was a Canadian meteorologist who pioneered the modelling the Earth's atmospheric circulation.

TOMCAT/SLIMCAT is an off-line chemical transport model (CTM), which models the time-dependent distribution of chemical species in the troposphere and stratosphere. It can be used to study topics such as ozone depletion and tropospheric pollution, and was one of the models used the IPCC report on Aviation and the Global Atmosphere. It incorporates a choice of detailed chemistry schemes for the troposphere or stratosphere, and an optional chemical data assimilation scheme.

The microwave sounding unit (MSU) was the predecessor to the Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit (AMSU).

The atmosphere of Jupiter is the largest planetary atmosphere in the Solar System. It is mostly made of molecular hydrogen and helium in roughly solar proportions; other chemical compounds are present only in small amounts and include methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and water. Although water is thought to reside deep in the atmosphere, its directly measured concentration is very low. The nitrogen, sulfur, and noble gas abundances in Jupiter's atmosphere exceed solar values by a factor of about three.

The Held–Hou Model is a model for the Hadley circulation of the atmosphere that would exist in the absence of atmospheric turbulence. The model was developed by Isaac Held and Arthur Hou in 1980.

Ocean general circulation models (OGCMs) are a particular kind of general circulation model to describe physical and thermodynamical processes in oceans. The oceanic general circulation is defined as the horizontal space scale and time scale larger than mesoscale. They depict oceans using a three-dimensional grid that include active thermodynamics and hence are most directly applicable to climate studies. They are the most advanced tools currently available for simulating the response of the global ocean system to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations. A hierarchy of OGCMs have been developed that include varying degrees of spatial coverage, resolution, geographical realism, process detail, etc.

Margaret Anne LeMone is an atmospheric scientist who uses both atmospheric observations and computer models to study the formation and development of clouds, the development of precipitation, and the structure of storms.

Lester Machta was an American meteorologist, the first director of the Air Resources Laboratory (ARL) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

M. Joan Alexander is an atmospheric scientist known for her research on gravity waves and their role in atmospheric circulation.