Related Research Articles

Organisation Todt was a civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior member of the Nazi Party. The organisation was responsible for a huge range of engineering projects both in Nazi Germany and in occupied territories from France to the Soviet Union during the Second World War. The organisation became notorious for using forced labour. From 1943 until 1945 during the late phase of the Third Reich, OT administered all constructions of concentration camps to supply forced labour to industry.

Fritz Todt was a German construction engineer and senior figure of the Nazi Party. He was the founder of Organisation Todt (OT), a military-engineering organisation that supplied German industry with forced labour, and served as Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition in Nazi Germany early in World War II, directing the entire German wartime military economy from that position.

Hugo Preuß (Preuss) was a German lawyer and liberal politician. He was the author of the draft version of the constitution that was passed by the Weimar National Assembly and came into force in August 1919. He based it on three principles: all political authority belongs to the people; that the state should be organized on a federal basis; and that the Reich should form a democratic Rechtsstaat within the international community.

Karl Christian Ludwig Hofer or Carl Hofer was a German expressionist painter. He was director of the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts.

Claudia Schmölders, also Claudia Henn-Schmölders is a German cultural scholar, author, and translator.

Erna Scheffler, born Friedental and later Haßlacher was a German senior judge.

Anna Blume and Bernhard Johannes Blume were German art photographers. They created sequences of large black-and-white photos of staged scenes in which they appeared themselves, with objects taking on a "life" of their own. Their works have been shown internationally in exhibitions and museums, including New York's MoMA. They are regarded as "among the pioneers of staged photography".

Mario von Bucovich, also known as Marius von Bucovich, was an Austrian photographer. He was born at Pula in the Istrian region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and held the title of Baron. His father, August, Freiherr von Bucovich (1852–1913), was a former Corvette Captain in the Austro-Hungarian navy and later an entrepreneur in the railroad concession sector. His mother was Greek.

The Reichsautobahn system was the beginning of the German autobahns under Nazi Germany. There had been previous plans for controlled-access highways in Germany under the Weimar Republic, and two had been constructed, but work had yet to start on long-distance highways. After previously opposing plans for a highway network, the Nazis embraced them after coming to power and presented the project as Hitler's own idea. They were termed "Adolf Hitler's roads" and presented as a major contribution to the reduction of unemployment. Other reasons for the project included enabling Germans to explore and appreciate their country, and there was a strong aesthetic element to the execution of the project under the Third Reich; military applications, although to a lesser extent than has often been thought; a permanent monument to the Third Reich, often compared to the pyramids; and general promotion of motoring as a modernization that in itself had military applications.

The Mangfall Bridge is a motorway bridge across the valley of the Mangfall north of Weyarn in Upper Bavaria, Germany, which carries Bundesautobahn 8 between Munich and Rosenheim. The original bridge, designed by German Bestelmeyer, opened in January 1936 as one of the first large bridges in the Reichsautobahn system and was influential in its design. Destroyed at the end of World War II, this bridge was replaced with a temporary structure in 1948; the current bridge consists of a replacement built in 1958–60 to a design by Gerd Lohmer and Ulrich Finsterwalder and a second span for traffic in one direction which was added in the late 1970s when the autobahn was widened to six lanes.

Asta Gröting is a contemporary artist. She works in a variety of media like sculpture, performance, and video. In her work, Gröting “is conceptually and emotionally asking questions of the social body by taking something away from it and allowing this absence to do the talking.”

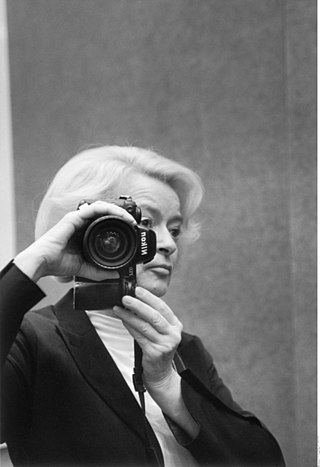

Angelika Platen is a German photographer known internationally for her portraits of artists.

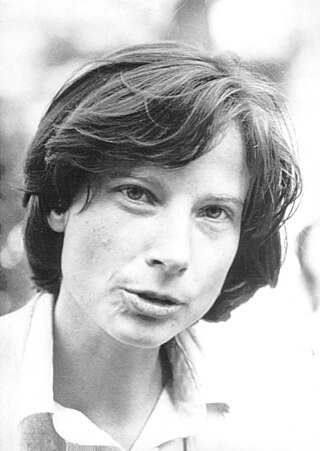

Evelyn Richter was a German art photographer known primarily for social documentary photography work in East Germany. She is notable for her black & white photography in which she documented working-class life, and which often showed influences of Dadaism and futurism. Her photography is focused on people in everyday life, including children, workers, artists and musicians.

Franz Grainer was a Bavarian photographer.

Oda Schottmüller was an expressive dancer, mask maker and sculptor. Schottmüller was most notable as a resistance fighter against the Nazis, through her association with a Berlin-based anti-fascist resistance group that she met through the sculptor Kurt Schumacher. The group would later be named by the Gestapo as Die Rote Kapelle.

Otto Friedrich Wilhelm Stapel, was a German Protestant and nationalist essayist. He was the editor of the influential antisemitic monthly magazine Deutsches Volkstum from 1919 until its shutdown by the Nazis in 1938.

Gundula Schulze Eldowy is a German photographer. In addition to her photographic and film work, she has created stories, poems, essays, sound collages and songs.

Ruth Wilhelmi-König was a German woman stage photographer.

Rosemarie Clausen ; was a German photographer. She worked as theatre and portrait photographer and received several awards for her work.

Liselotte Strelow was a German photographer.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Anne Maxwell, Picture Imperfect: Photography and Eugenics, 1870–1940, Brighton, Sussex / Portland, Oregon: Sussex Academic Press, 2008, ISBN 9781845192396, p. 194.

- 1 2 Ute Eskildsen et al., ed., Fotografieren hieß Teilnehmen: Fotografinnen der Weimarer Republik, Catalogue of exhibitions at Museum Folkwang Essen, Fundació "La Caixa", Barcelona, Jewish Museum, New York, Düsseldorf: Richter, 1994, ISBN 9783928762267, n.p. (in German)

- ↑ Maureen Grimm, "Leben und Werk", in section Erna Lendvai-Dircksen—eine völkische Porträtfotografin?, in Menschenbild und Volksgesicht: Positionen zur Porträtfotografie im Nationalsozialismus, ed. Falk Blask and Thomas Friedrich, Berliner Blätter Sonderheft 36, Münster: LIT, 2005, ISBN 9783825886974, pp. 39–48, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carmen Böker, "Das vermessene Gesicht" [ permanent dead link ], Berliner Zeitung 23 July 2005 (in German)

- ↑ Sarah Jost, "Unter Volksgenossen. Agrarromantik und Großstadtfeindschaft", in Menschenbild und Volksgesicht, pp. 105–20, p. 110 (in German)

- ↑ Grimm, p. 42.

- ↑ Richard T. Gray, About Face: German Physiognomic Thought from Lavater to Auschwitz, Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University, 2004, ISBN 9780814331798, , p. 396.

- ↑ Claudia Gabriele Philipp, "'Die schöne Straße im Bau und unter Verkehr'. Zur Konstituierung des Mythos von der Autobahn durch die mediale Verbreitung und Ästhetik der Fotografie", in Reichsautobahn: Pyramiden des Dritten Reichs. Analysen zur Ästhetik eines unbewältigten Mythos, ed. Reiner Stommer with Claudia Gabriele Philipp, Marburg: Jonas, 1982, ISBN 9783922561125, pp. 111–34, p. 117 (in German)

- 1 2 Ulrich Hägele, "Erna Lendvai-Dircksen und die Ikonografie der völkischen Fotografie", in Menschenbild und Volksgesicht, pp. 78–98, p. 78 (in German)

- ↑ Cited in Philipp, p. 117 from Lendvai-Dircksen's introduction to the second edition of the book: "[Er wollte] das Antlitz seiner Reichsautobahnarbeiter aus den verschiedenen Gegenden des Vaterlandes fotografisch dargestellt sehen".

- ↑ Philipp, pp. 120–21.

- ↑ Philipp, pp. 125–27.

- ↑ Philipp, pp. 121–22.

- 1 2 Maxwell, p. 199 [ permanent dead link ].

- ↑ Philipp, pp. 122–24.

- ↑ Philipp, pp. 121, 123: "Nach Jahren der Arbeitslosigkeit schaffe ich für sieben Söhne und eine Tochter wieder ehrliches Brot".

- ↑ Maxwell, p. 189; Plate 7.10, p. 190 [ permanent dead link ].

- 1 2 3 Claudia Gabriele Philipp and Horst W. Scholz, Photographische Perspektiven aus den Zwanziger Jahren, Dokumente der Photographie 4, exhibition catalogue, Hamburg: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, 1994, ISBN 9783923859221, p. 208 (in German)

- ↑ Frauenobjektiv: Fotografinnen 1940 bis 1950, ed. Petra Rosgen, exhibition catalogue, Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Cologne: Wienand, 2001, ISBN 9783879097524, pp. 51–52.

- 1 2 Claudia Gabriele Philipp, "Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (1883–1962): Präsentantin einer weiblichen Kunsttradition oder Propagandistin des Nationalsozialismus?", in Frauen und Macht: der alltägliche Beitrag der Frauen zur Politik des Patriarchats, ed. Barbara Schaeffer-Hegel, papers from a conference held at Technische Universität Berlin, November 1983, 1988; 2nd ed. Feministische Theorie und Politik 2, Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus, 1988, ISBN 9783890852386, pp. 58–74, p. 64 (in German)

- ↑ Karla Fohrbeck, Handbuch der Kulturpreise und der individuellen Künstlerförderung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1979–1985, Bundesministerium des Innern, Kultur und Staat, Studien zur Kulturpolitik, Cologne: DuMont, 1985, ISBN 9783770117475, p. 576 (in German)

- ↑ The German Photographic Annual 1969 (translation of Das Deutsche Lichtbild), ed. Wolf Strache and Otto Steinert, Stuttgart: Dr. Wolf Strache, 1968, OCLC 45673189, p. 151 (in German)

- ↑ Maxwell, p. 195 [ permanent dead link ].

- ↑ Maxwell, p. 200 [ permanent dead link ].

- ↑ Or even earlier; Gray, p. 354 judges her views about the "authenticity" of rural people as expressed in their faces to be "identical in many ways" to those of Johann Kaspar Lavater in the second half of the 17th century.

- ↑ Leesa Rittelmann, "Facing Off: Photography, Physiognomy, and National Identity in the Modern German Photobook", Radical History Review 106 (2010) 137–61 (abstract)

- ↑ Eskildsen et al., n.p.

- ↑ Naomi Rosenblum, A History of Women Photographers, Paris/New York: Abbeville, 1994, ISBN 9781558597617, p. 334.

- ↑ "Hochbetagt starb Frau Erna Lendvai-Dircksen in Coburg", Coburger Tageblatt, 10 May 1962, cited in "Seien Sie doch vernünftig!": Frauen der Coburger Geschichte, ed. Gaby Franger, Exhibition catalogue, Coburg: Landesbibliothek Coburg, 2008, ISBN 9783980800693, p. 286 (in German)

- ↑ Thomas Friedrich, "Erna Lendvai-Dircksen selbständige Veröffentlichungen", in Menschenbild und Volksgesicht, pp. 49–53, p. 53 (in German)