Related Research Articles

Stanley Milgram was an American social psychologist known for his controversial experiments on obedience conducted in the 1960s during his professorship at Yale.

Georg Simmel was a German sociologist, philosopher, and critic.

Urban sociology is the sociological study of cities and urban life. One of the field’s oldest sub-disciplines, urban sociology studies and examines the social, historical, political, cultural, economic, and environmental forces that have shaped urban environments. Like most areas of sociology, urban sociologists use statistical analysis, observation, archival research, census data, social theory, interviews, and other methods to study a range of topics, including poverty, racial residential segregation, economic development, migration and demographic trends, gentrification, homelessness, blight and crime, urban decline, and neighborhood changes and revitalization. Urban sociological analysis provides critical insights that shape and guide urban planning and policy-making.

In sociology, social distance describes the distance between individuals or social groups in society, including dimensions such as social class, race/ethnicity, gender or sexuality. Members of different groups mix less than members of the same group. It is the measure of nearness or intimacy that an individual or group feels towards another individual or group in a social network or the level of trust one group has for another and the extent of perceived likeness of beliefs.

Social influence comprises the ways in which individuals adjust their behavior to meet the demands of a social environment. It takes many forms and can be seen in conformity, socialization, peer pressure, obedience, leadership, persuasion, sales, and marketing. Typically social influence results from a specific action, command, or request, but people also alter their attitudes and behaviors in response to what they perceive others might do or think. In 1958, Harvard psychologist Herbert Kelman identified three broad varieties of social influence.

- Compliance is when people appear to agree with others but actually keep their dissenting opinions private.

- Identification is when people are influenced by someone who is liked and respected, such as a famous celebrity.

- Internalization is when people accept a belief or behavior and agree both publicly and privately.

The small-world experiment comprised several experiments conducted by Stanley Milgram and other researchers examining the average path length for social networks of people in the United States. The research was groundbreaking in that it suggested that human society is a small-world-type network characterized by short path-lengths. The experiments are often associated with the phrase "six degrees of separation", although Milgram did not use this term himself.

In the fields of sociology and social psychology, a breaching experiment is an experiment that seeks to examine people's reactions to violations of commonly accepted social rules or norms. Breaching experiments are most commonly associated with ethnomethodology, and in particular the work of Harold Garfinkel. Breaching experiments involve the conscious exhibition of "unexpected" behavior/violation of social norms, an observation of the types of social reactions such behavioral violations engender, and an analysis of the social structure that makes these social reactions possible. The idea of studying the violation of social norms and the accompanying reactions has bridged across social science disciplines, and is today used in both sociology and psychology.

The sociology of culture, and the related cultural sociology, concerns the systematic analysis of culture, usually understood as the ensemble of symbolic codes used by a member of a society, as it is manifested in the society. For Georg Simmel, culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history". Culture in the sociological field is analyzed as the ways of thinking and describing, acting, and the material objects that together shape a group of people's way of life.

In sociology, social psychology studies the relationship between the individual and society. Although studying many of the same substantive topics as its counterpart in the field of psychology, sociological social psychology places relatively more emphasis on the influence of social structure and culture on individual outcomes, such as personality, behavior, and one's position in social hierarchies. Researchers broadly focus on higher levels of analysis, directing attention mainly to groups and the arrangement of relationships among people. This subfield of sociology is broadly recognized as having three major perspectives: Symbolic interactionism, social structure and personality, and structural social psychology.

Cyranoids are "people who do not speak thoughts originating in their own central nervous system: Rather, the words they speak originate in the mind of another person who transmits these words to the cyranoid by radio transmission". The concept was developed by psychologist Stanley Milgram as a research method.

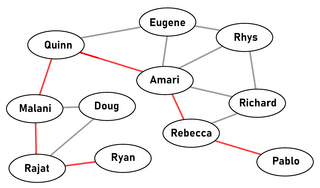

In social network analysis and mathematical sociology, interpersonal ties are defined as information-carrying connections between people. Interpersonal ties, generally, come in three varieties: strong, weak or absent. Weak social ties, it is argued, are responsible for the majority of the embeddedness and structure of social networks in society as well as the transmission of information through these networks. Specifically, more novel information flows to individuals through weak rather than strong ties. Because our close friends tend to move in the same circles that we do, the information they receive overlaps considerably with what we already know. Acquaintances, by contrast, know people that we do not, and thus receive more novel information.

Compliance is a response—specifically, a submission—made in reaction to a request. The request may be explicit or implicit. The target may or may not recognize that they are being urged to act in a particular way.

Triad refers to a group of three people in sociology. It is one of the simplest human groups that can be studied and is mostly looked at by microsociology. The study of triads and dyads was pioneered by German sociologist Georg Simmel at the end of the nineteenth century.

Consequential strangers are personal connections other than family and close friends. Also known as "peripheral" or "weak" ties, they lie in the broad social territory between strangers and intimates. The term was coined by Karen L. Fingerman and further developed by Melinda Blau, who collaborated with the psychologist to explore and popularize the concept.

Urban computing is an interdisciplinary field which pertains to the study and application of computing technology in urban areas. This involves the application of wireless networks, sensors, computational power, and data to improve the quality of densely populated areas. Urban computing is the technological framework for smart cities.

A social network is a social structure consisting of a set of social actors, sets of dyadic ties, and other social interactions between actors. The social network perspective provides a set of methods for analyzing the structure of whole social entities as well as a variety of theories explaining the patterns observed in these structures. The study of these structures uses social network analysis to identify local and global patterns, locate influential entities, and examine network dynamics. For instance, social network analysis has been used in studying the spread of misinformation on social media platforms or analyzing the influence of key figures in social networks.

Six degrees of separation is the idea that all people are six or fewer social connections away from each other. As a result, a chain of "friend of a friend" statements can be made to connect any two people in a maximum of six steps. It is also known as the six handshakes rule. Mathematically it means that a person shaking hands with 30 people, and then those 30 shaking hands with 30 other people, would after repeating this 6 times allow every person in a population as large as the United States to have shaken hands.

Experimenter: The Stanley Milgram Story or Experimenter, is a 2015 American biographical drama film written, directed and co-produced by Michael Almereyda. It depicts the experiments Milgram experiment in 1961 by a social psychologist Stanley Milgram. The film, co-produced by and starring Danny A. Abeckaser, also stars Peter Sarsgaard, Winona Ryder, Jim Gaffigan, Kellan Lutz, Dennis Haysbert, Anthony Edwards, Lori Singer, Josh Hamilton, Anton Yelchin, John Leguizamo.

Inclusive fitness in humans is the application of inclusive fitness theory to human social behaviour, relationships and cooperation.

A stranger is a person who is unknown to another person or group. Because of this unknown status, a stranger may be perceived as a threat until their identity and character can be ascertained. Different classes of strangers have been identified for social science purposes, and the tendency for strangers and foreigners to overlap has been examined.

References

- 1 2 3 Milgram, Stanley. 1972. "The Familiar Stranger: An Aspect of Urban Anonymity". in The Division 8 Newsletter, Division of Personality and Social Psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association

- 1 2 Paulos, Eric, and Elizabeth Goodman. "The Familiar Stranger: Anxiety, Comfort, and Play in Public Places." Proceedings of SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY: ACM, 2004. 223-30

- 1 2 Sun, Lijun; Axhausen, Kay W.; Lee, Der-Horng; Huang, Xianfeng (2013-08-20). "Understanding metropolitan patterns of daily encounters". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (34): 13774–13779. arXiv: 1301.5979 . Bibcode:2013PNAS..11013774S. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306440110 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3752247 . PMID 23918373.

- ↑ Nitin Agarwal & others (2007) "Searching for Familiar Strangers on Blogosphere: Problems and Challenges" NSF Symposium on Next-Generation Data Mining and Cyber-enabled Discovery and Innovation (NGDM). 2007.

- 1 2 3 see: Simmel Georg. "The Stranger". [in] The Sociology of Georg Simmel. By Kurt Wolff, New York: Free Press, 1950, pp 402 - 408

- ↑ Liang, Di; Li, Xiang; Zhang, Yi-Qing (2016-01-01). "Identifying familiar strangers in human encounter networks". EPL. 116 (1): 18006. Bibcode:2016EL....11618006L. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/116/18006. ISSN 0295-5075.

- ↑ Felder, Maxime (2020). "Strong, Weak and Invisible Ties: A Relational Perspective on Urban Coexistence". Sociology. 54 (4): 675–692. doi: 10.1177/0038038519895938 . S2CID 213368620.

- ↑ Blokland, Talja; Nast, Julia (July 2014). "From Public Familiarity to Comfort Zone: The Relevance of Absent Ties for Belonging in Berlin's Mixed Neighbourhoods". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 38 (4): 1142–11 59. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12126.