The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is a U.S. fantasy and science fiction magazine, first published in 1949 by Mystery House, a subsidiary of Lawrence Spivak's Mercury Press. Editors Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas had approached Spivak in the mid-1940s about creating a fantasy companion to Spivak's existing mystery title, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. The first issue was titled The Magazine of Fantasy, but the decision was quickly made to include science fiction as well as fantasy, and the title was changed correspondingly with the second issue. F&SF was quite different in presentation from the existing science fiction magazines of the day, most of which were in pulp format: it had no interior illustrations, no letter column, and text in a single-column format, which in the opinion of science fiction historian Mike Ashley "set F&SF apart, giving it the air and authority of a superior magazine".

Science Fantasy, which also appeared under the titles Impulse and SF Impulse, was a British fantasy and science fiction magazine, launched in 1950 by Nova Publications as a companion to Nova's New Worlds. Walter Gillings was editor for the first two issues, and was then replaced by John Carnell, the editor of New Worlds, as a cost-saving measure. Carnell edited both magazines until Nova went out of business in early 1964. The titles were acquired by Roberts & Vinter, who hired Kyril Bonfiglioli to edit Science Fantasy; Bonfiglioli changed the title to Impulse in early 1966, but the new title led to confusion with the distributors and sales fell, though the magazine remained profitable. The title was changed again to SF Impulse for the last few issues. Science Fantasy ceased publication the following year, when Roberts & Vinter came under financial pressure after their printer went bankrupt.

Unknown was an American pulp fantasy fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1943 by Street & Smith, and edited by John W. Campbell. Unknown was a companion to Street & Smith's science fiction pulp, Astounding Science Fiction, which was also edited by Campbell at the time; many authors and illustrators contributed to both magazines. The leading fantasy magazine in the 1930s was Weird Tales, which focused on shock and horror. Campbell wanted to publish a fantasy magazine with more finesse and humor than Weird Tales, and put his plans into action when Eric Frank Russell sent him the manuscript of his novel Sinister Barrier, about aliens who own the human race. Unknown's first issue appeared in March 1939; in addition to Sinister Barrier, it included H. L. Gold's "Trouble With Water", a humorous fantasy about a New Yorker who meets a water gnome. Gold's story was the first of many in Unknown to combine commonplace reality with the fantastic.

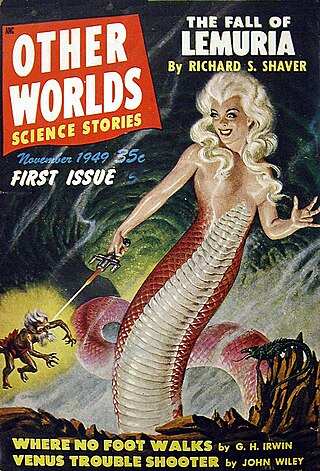

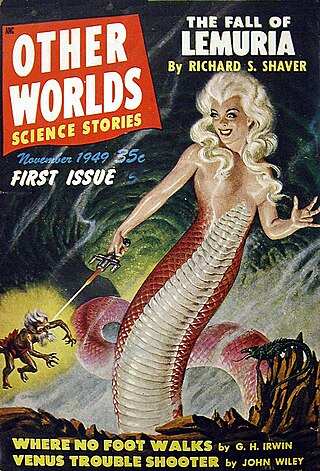

Other Worlds, Universe Science Fiction, and Science Stories were three related US magazines edited by Raymond A. Palmer. Other Worlds was launched in November 1949 by Palmer's Clark Publications and lasted for four years in its first run, with well-received stories such as "Enchanted Village" by A. E. van Vogt and "Way in the Middle of the Air", one of Ray Bradbury's "Martian Chronicle" stories. Since Palmer was both publisher and editor, he was free to follow his own editorial policy, and presented a wide array of science fiction.

Tales of Wonder was a British science fiction magazine published from 1937 to 1942, with Walter Gillings as editor. It was published by The World's Work, a subsidiary of William Heinemann, as part of a series of genre titles that included Tales of Mystery and Detection and Tales of the Uncanny. Gillings was able to attract some good material, despite the low payment rates he was able to offer; he also included many reprints from U.S. science fiction magazines. The magazine was apparently more successful than the other genre titles issued by The World's Work, since Tales of Wonder was the only one to publish more than a single issue.

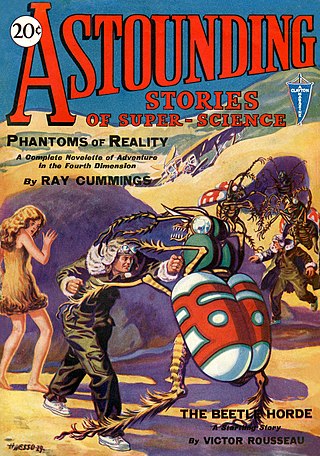

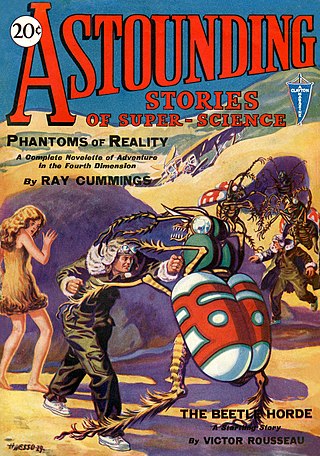

Analog Science Fiction and Fact is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science, the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William Clayton, and edited by Harry Bates. Clayton went bankrupt in 1933 and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The new editor was F. Orlin Tremaine, who soon made Astounding the leading magazine in the nascent pulp science fiction field, publishing well-regarded stories such as Jack Williamson's Legion of Space and John W. Campbell's "Twilight". At the end of 1937, Campbell took over editorial duties under Tremaine's supervision, and the following year Tremaine was let go, giving Campbell more independence. Over the next few years Campbell published many stories that became classics in the field, including Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, A. E. van Vogt's Slan, and several novels and stories by Robert A. Heinlein. The period beginning with Campbell's editorship is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

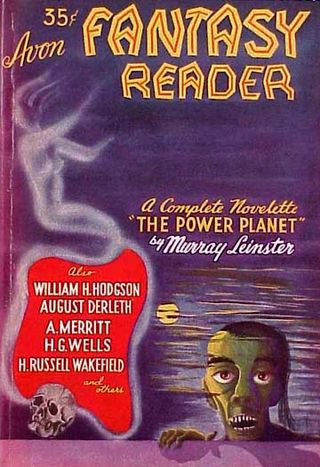

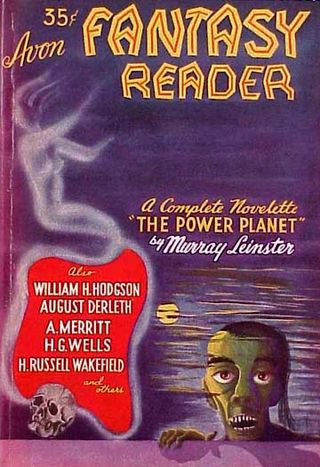

Avon published three related magazines in the late 1940s and early 1950s, titled Avon Fantasy Reader, Avon Science Fiction Reader, and Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader. These were digest size magazines which reprinted science fiction and fantasy literature by now well-known authors. They were edited by Donald A. Wollheim and published by Avon.

Nebula Science Fiction was the first Scottish science fiction magazine. It was published from 1952 to 1959, and was edited by Peter Hamilton, a young Scot who was able to take advantage of spare capacity at his parents' printing company, Crownpoint, to launch the magazine. Because Hamilton could only print Nebula when Crownpoint had no other work, the schedule was initially erratic. In 1955 he moved the printing to a Dublin-based firm, and the schedule became a little more regular, with a steady monthly run beginning in 1958 that lasted into the following year. Nebula's circulation was international, with only a quarter of the sales in the United Kingdom; this led to disaster when South Africa and Australia imposed import controls on foreign periodicals at the end of the 1950s. Excise duties imposed in the UK added to Hamilton's financial burdens, and he was rapidly forced to close the magazine. The last issue was dated June 1959.

Science Fiction Adventures was a British digest-size science fiction magazine, published from 1958 to 1963 by Nova Publications as a companion to New Worlds and Science Fantasy. It was edited by John Carnell. Science Fiction Adventures began as a reprint of the American magazine of the same name, Science Fiction Adventures, but after only three issues the American version ceased publication. Instead of closing down the British version, which had growing circulation, Nova decided to continue publishing it with new material. The fifth issue was the last which contained stories reprinted from the American magazine, though Carnell did occasionally reprint stories thereafter from other sources.

Dynamic Science Stories was an American pulp magazine which published two issues, dated February and April 1939. A companion to Marvel Science Stories, it was edited by Robert O. Erisman and published by Western Fiction Publishing. Among the better known authors who appeared in its pages were L. Sprague de Camp and Manly Wade Wellman.

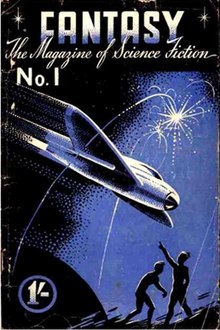

Fantasy was a British pulp science fiction magazine which published three issues in London between 1938 and 1939. The editor was T. Stanhope Sprigg; when the war started, he enlisted in the RAF and the magazine was closed down. The publisher, George Newnes Ltd, paid respectable rates, and as a result Sprigg was able to obtain some good quality material, including stories by John Wyndham, Eric Frank Russell, and John Russell Fearn.

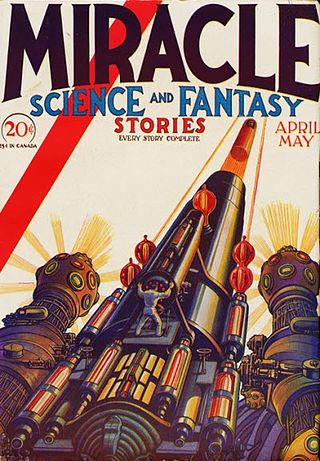

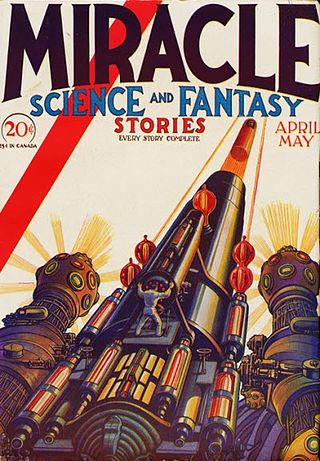

Miracle Science and Fantasy Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine which published two issues in 1931. The fiction was unremarkable, but the cover art and illustrations, by Elliott Dold, were high quality, and have made the magazine a collector's item. The magazine ceased publication when Dold became ill and was unable to continue his duties both as editor and artist.

Strange Stories was a pulp magazine which ran for thirteen issues from 1939 to 1941. It was edited by Mort Weisinger, who was not credited. Contributors included Robert Bloch, Eric Frank Russell, C. L. Moore, August Derleth, and Henry Kuttner. Strange Stories was a competitor to the established leader in weird fiction, Weird Tales. With the launch, also in 1939, of the well-received Unknown, Strange Stories was unable to compete. It ceased publication in 1941 when Weisinger left to edit Superman comic books.

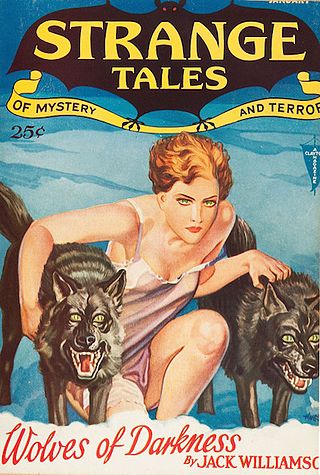

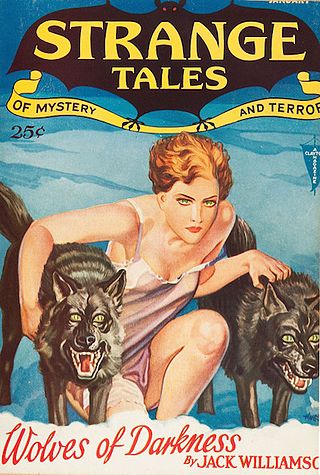

Strange Tales was an American pulp magazine first published from 1931 to 1933 by Clayton Publications. It specialized in fantasy and weird fiction, and was a significant competitor to Weird Tales, the leading magazine in the field. Its published stories include "Wolves of Darkness" by Jack Williamson, as well as work by Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith. The magazine ceased publication when Clayton entered bankruptcy. It was temporarily revived by Wildside Press, which published three issues edited by Robert M. Price from 2003 to 2007.

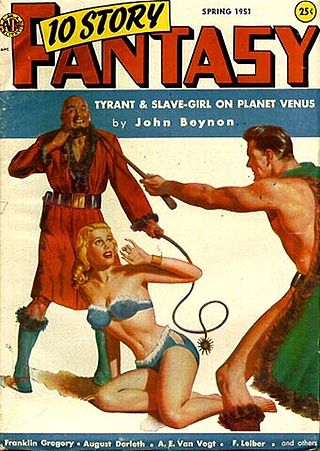

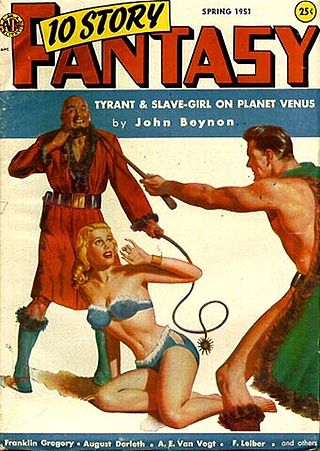

10 Story Fantasy was a science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine which was launched in 1951. The market for pulp magazines was already declining by that time, and the magazine only lasted a single issue. The stories were of generally good quality, and included work by many well-known writers, such as John Wyndham, A.E. van Vogt and Fritz Leiber. The most famous story it published was Arthur C. Clarke's "Sentinel from Eternity", which later became part of the basis of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Two Complete Science-Adventure Books was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published by Fiction House, which lasted for eleven issues between 1950 and 1954 as a companion to Planet Stories. Each issue carried two novels or long novellas. It was initially intended to carry only reprints, but soon began to publish original stories. Contributors included Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, and James Blish. The magazine folded in 1954, almost at the end of the pulp era.

Vargo Statten Science Fiction Magazine was a British science fiction magazine which published nineteen issues between 1954 and 1956. It was initially published by Scion Press, with control passing to a successor company, Scion Distributors, after Scion went bankrupt in early 1954. At the end of 1954, as part payment for a debt, Scion Distributors handed control of the magazine to Dragon Press, who continued it for another twelve issues. E. C. Tubb and John Russell Fearn were regular contributors, and Kenneth Bulmer also published several stories in the magazine. Barrington Bayley's first published story, "Combat's End", appeared in May 1954. The editor was initially Alistair Paterson, but after seven issues Fearn took the helm: "Vargo Statten" was one of Fearn's aliases, and the magazine's title had been chosen because of his popularity. Neither Paterson nor Fearn had enough of a budget to attract good quality submissions, and a printing strike in 1956 brought an end to the magazine's life.

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.

Beatrice Mahaffey (1928–1987) was an American science fiction fan and editor. She met Raymond Palmer in 1949 at the World Science Fiction Convention in Cleveland, and was hired to assist him at Clark Publications, his publishing company. She worked on Other Worlds from May 1950; Palmer was incapacitated by an accident for a while shortly after she was hired, though he remained involved from his hospital bed. She was listed as coeditor from November 1952 to July 1953 and from May 1955 to November 1955. She coedited both Science Stories and Universe Science Fiction with Palmer, along with the first four issues of Mystic Magazine, from November 1953 to May 1954. Science fiction historians Mike Ashley and E.F. Casebeer both consider that she had a strong positive influence on the magazines, and was probably responsible for acquiring much of the better material Palmer published. After Palmer closed his offices in Evanston, Illinois in 1955, Mahaffey continued to work on the magazine by mail from Cincinnati. In 1956, an unexpected tax bill forced Palmer to lay off Mahaffey, and he ran the magazine by himself from that point on.

Between 1965 and 1976, Sol Cohen published over a hundred issues of science fiction magazines under a set of related titles.