The New Wave was a science fiction style of the 1960s and 1970s, characterized by a great degree of experimentation with the form and content of stories, greater imitation of the styles of non-science fiction literature, and an emphasis on the psychological and social sciences as opposed to the physical sciences. New Wave authors often considered themselves as part of the modernist tradition of fiction, and the New Wave was conceived as a deliberate change from the traditions of the science fiction characteristic of pulp magazines, which many of the writers involved considered irrelevant or unambitious.

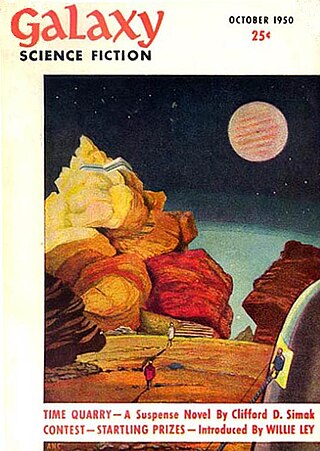

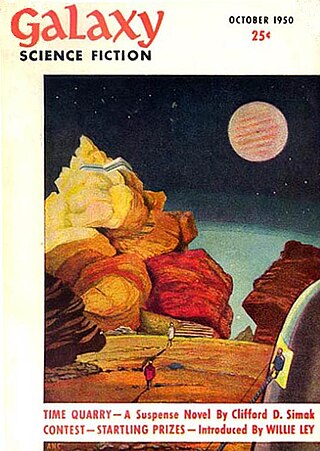

Galaxy Science Fiction was an American digest-size science fiction magazine, published in Boston from 1950 to 1980. It was founded by a French-Italian company, World Editions, which was looking to break into the American market. World Editions hired as editor H. L. Gold, who rapidly made Galaxy the leading science fiction magazine of its time, focusing on stories about social issues rather than technology.

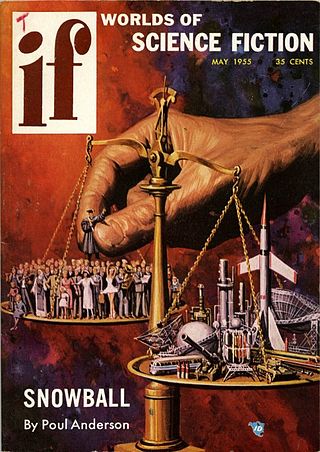

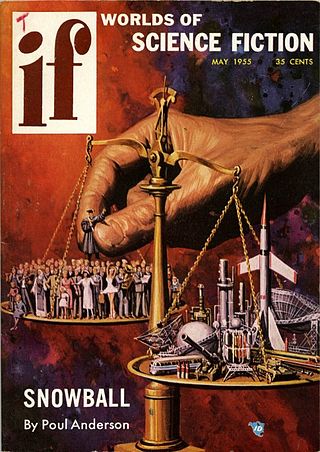

If was an American science fiction magazine launched in March 1952 by Quinn Publications, owned by James L. Quinn.

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is a U.S. fantasy and science-fiction magazine, first published in 1949 by Mystery House, a subsidiary of Lawrence Spivak's Mercury Press. Editors Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas had approached Spivak in the mid-1940s about creating a fantasy companion to Spivak's existing mystery title, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. The first issue was titled The Magazine of Fantasy, but the decision was quickly made to include science fiction as well as fantasy, and the title was changed correspondingly with the second issue. F&SF was quite different in presentation from the existing science-fiction magazines of the day, most of which were in pulp format: it had no interior illustrations, no letter column, and text in a single-column format, which in the opinion of science-fiction historian Mike Ashley "set F&SF apart, giving it the air and authority of a superior magazine".

Unknown was an American pulp fantasy fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1943 by Street & Smith, and edited by John W. Campbell. Unknown was a companion to Street & Smith's science fiction pulp, Astounding Science Fiction, which was also edited by Campbell at the time; many authors and illustrators contributed to both magazines. The leading fantasy magazine in the 1930s was Weird Tales, which focused on shock and horror. Campbell wanted to publish a fantasy magazine with more finesse and humor than Weird Tales, and put his plans into action when Eric Frank Russell sent him the manuscript of his novel Sinister Barrier, about aliens who own the human race. Unknown's first issue appeared in March 1939; in addition to Sinister Barrier, it included H. L. Gold's "Trouble With Water", a humorous fantasy about a New Yorker who meets a water gnome. Gold's story was the first of many in Unknown to combine commonplace reality with the fantastic.

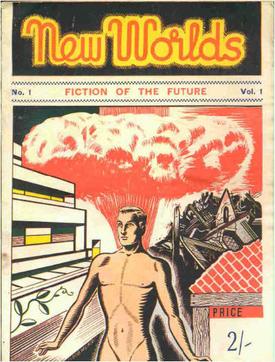

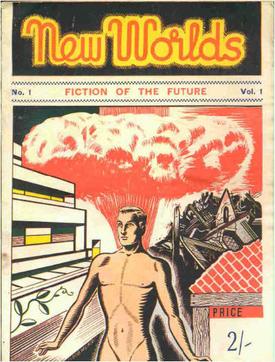

New Worlds was a British science fiction magazine that began in 1936 as a fanzine called Novae Terrae. John Carnell, who became Novae Terrae's editor in 1939, renamed it New Worlds that year. He was instrumental in turning it into a professional publication in 1946 and was the first editor of the new incarnation. It became the leading UK science fiction magazine; the period to 1960 has been described by science fiction historian Mike Ashley as the magazine's "Golden Age".

Edward John Carnell was a British science fiction editor known for editing New Worlds in 1946 then from 1949 to 1963. He also edited Science Fantasy from the 1950s. After the magazines were sold to another publisher he left to launch the New Writings in SF anthology series, editing 21 issues until his death, after which the series was continued by Kenneth Bulmer for a further 9 issues.

Infinity Science Fiction was an American science fiction magazine, edited by Larry T. Shaw, and published by Royal Publications. The first issue, which appeared in November 1955, included Arthur C. Clarke's "The Star", a story about a planet destroyed by a nova that turns out to have been the Star of Bethlehem; it won the Hugo Award for that year. Shaw obtained stories from some of the leading writers of the day, including Brian Aldiss, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Sheckley, but the material was of variable quality. In 1958 Irwin Stein, the owner of Royal Publications, decided to shut down Infinity; the last issue was dated November 1958.

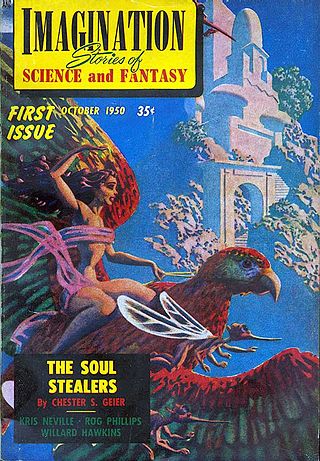

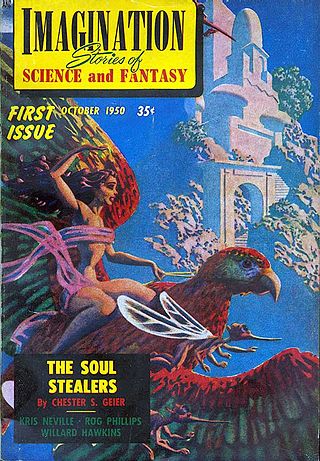

Imagination was an American fantasy and science fiction magazine first published in October 1950 by Raymond Palmer's Clark Publishing Company. The magazine was sold almost immediately to Greenleaf Publishing Company, owned by William Hamling, who published and edited it from the third issue, February 1951, for the rest of the magazine's life. Hamling launched a sister magazine, Imaginative Tales, in 1954; both ceased publication at the end of 1958 in the aftermath of major changes in US magazine distribution due to the liquidation of American News Company.

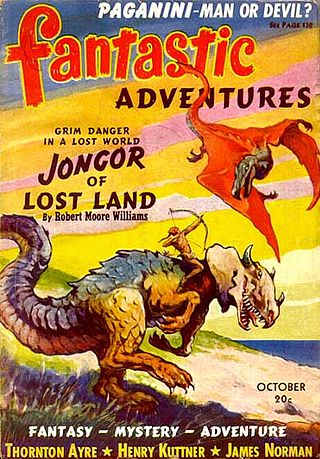

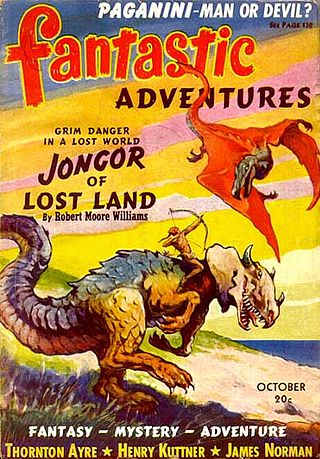

Fantastic Adventures was an American pulp fantasy and science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1953 by Ziff-Davis. It was initially edited by Raymond A. Palmer, who was also the editor of Amazing Stories, Ziff-Davis's other science fiction title. The first nine issues were in bedsheet format, but in June 1940 the magazine switched to a standard pulp size. It was almost cancelled at the end of 1940, but the October 1940 issue enjoyed unexpectedly good sales, helped by a strong cover by J. Allen St. John for Robert Moore Williams' Jongor of Lost Land. By May 1941 the magazine was on a regular monthly schedule. Historians of science fiction consider that Palmer was unable to maintain a consistently high standard of fiction, but Fantastic Adventures soon developed a reputation for light-hearted and whimsical stories. Much of the material was written by a small group of writers under both their own names and house names. The cover art, like those of many other pulps of the era, focused on beautiful women in melodramatic action scenes. One regular cover artist was H.W. McCauley, whose glamorous "MacGirl" covers were popular with the readers, though the emphasis on depictions of attractive and often partly clothed women did draw some objections.

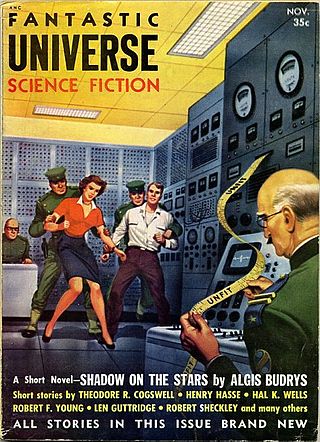

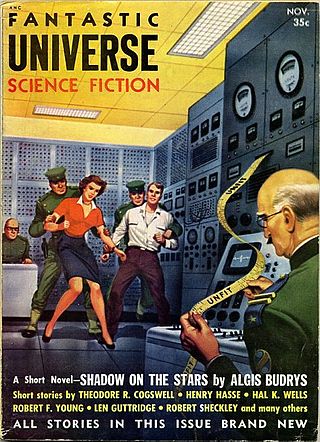

Fantastic Universe was a U.S. science fiction magazine which began publishing in the 1950s. It ran for 69 issues, from June 1953 to March 1960, under two different publishers. It was part of the explosion of science fiction magazine publishing in the 1950s in the United States, and was moderately successful, outlasting almost all of its competitors. The main editors were Leo Margulies (1954–1956) and Hans Stefan Santesson (1956–1960).

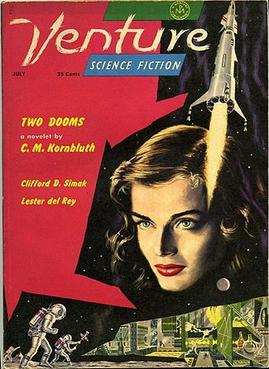

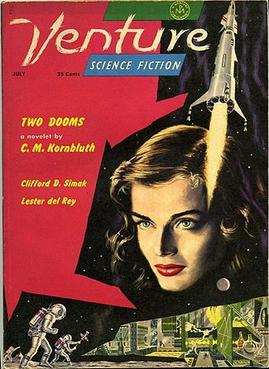

Venture Science Fiction was an American digest-size science fiction magazine, first published from 1957 to 1958, and revived for a brief run in 1969 and 1970. Ten issues were published of the 1950s version, with another six in the second run. It was founded in both instances as a companion to The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Robert P. Mills edited the 1950s version, and Edward L. Ferman was editor during the second run. A British edition appeared for 28 issues between 1963 and 1965; it reprinted material from The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction as well as from the US edition of Venture. There was also an Australian edition, which was identical to the British version but dated two months later.

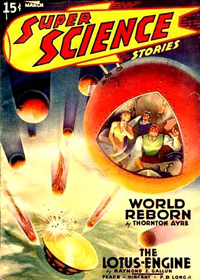

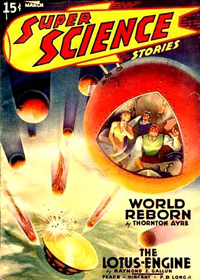

Super Science Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine published by Popular Publications from 1940 to 1943, and again from 1949 to 1951. Popular launched it under their Fictioneers imprint, which they used for magazines, paying writers less than one cent per word. Frederik Pohl was hired in late 1939, at 19 years old, to edit the magazine; he also edited Astonishing Stories, a companion science fiction publication. Pohl left in mid-1941 and Super Science Stories was given to Alden H. Norton to edit; a few months later Norton rehired Pohl as an assistant. Popular gave Pohl a very low budget, so most manuscripts submitted to Super Science Stories had already been rejected by the higher-paying magazines. This made it difficult to acquire good fiction, but Pohl was able to acquire stories for the early issues from the Futurians, a group of young science fiction fans and aspiring writers.

Science Fiction Quarterly was an American pulp science fiction magazine that was published from 1940 to 1943 and again from 1951 to 1958. Charles Hornig served as editor for the first two issues; Robert A. W. Lowndes edited the remainder. Science Fiction Quarterly was launched by publisher Louis Silberkleit during a boom in science fiction magazines at the end of the 1930s. Silberkleit launched two other science fiction titles at about the same time: all three ceased publication before the end of World War II, falling prey to slow sales and paper shortages. In 1950 and 1951, as the market improved, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction and Science Fiction Quarterly. By the time Science Fiction Quarterly ceased publication in 1958, it was the last surviving science fiction pulp magazine, all other survivors having changed to different formats.

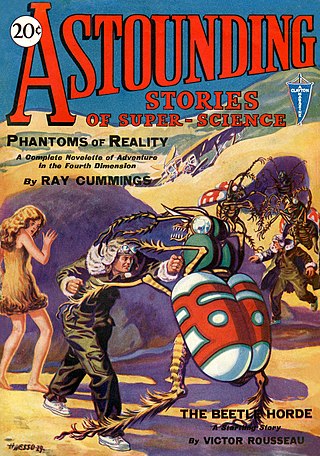

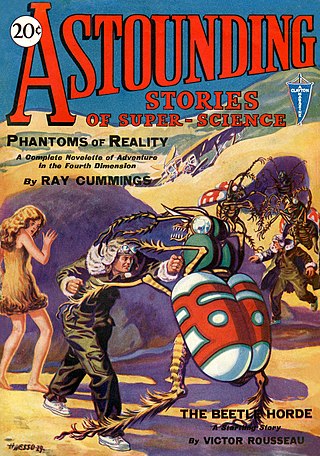

Analog Science Fiction and Fact is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science, the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William Clayton, and edited by Harry Bates. Clayton went bankrupt in 1933 and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The new editor was F. Orlin Tremaine, who soon made Astounding the leading magazine in the nascent pulp science fiction field, publishing well-regarded stories such as Jack Williamson's Legion of Space and John W. Campbell's "Twilight". At the end of 1937, Campbell took over editorial duties under Tremaine's supervision, and the following year Tremaine was let go, giving Campbell more independence. Over the next few years Campbell published many stories that became classics in the field, including Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, A. E. van Vogt's Slan, and several novels and stories by Robert A. Heinlein. The period beginning with Campbell's editorship is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

New Writings in SF was a series of thirty British science fiction original anthologies published from 1964 to 1977 under the successive editorships of John Carnell from 1964 to 1972 and Kenneth Bulmer from 1973 to 1977. There were in addition four special volumes compiling material from the regular volumes. The series showcased the work of mostly British and Commonwealth science fiction authors, and "provided a forum for a generation of newer authors."

Nebula Science Fiction was the first Scottish science fiction magazine. It was published from 1952 to 1959, and was edited by Peter Hamilton, a young Scot who was able to take advantage of spare capacity at his parents' printing company, Crownpoint, to launch the magazine. Because Hamilton could only print Nebula when Crownpoint had no other work, the schedule was initially erratic. In 1955 he moved the printing to a Dublin-based firm, and the schedule became a little more regular, with a steady monthly run beginning in 1958 that lasted into the following year. Nebula's circulation was international, with only a quarter of the sales in the United Kingdom; this led to disaster when South Africa and Australia imposed import controls on foreign periodicals at the end of the 1950s. Excise duties imposed in the UK added to Hamilton's financial burdens, and he was rapidly forced to close the magazine. The last issue was dated June 1959.

Future Science Fiction and Science Fiction Stories were two American science fiction magazines that were published under various names between 1939 and 1943 and again from 1950 to 1960. Both publications were edited by Charles Hornig for the first few issues; Robert W. Lowndes took over in late 1941 and remained editor until the end. The initial launch of the magazines came as part of a boom in science fiction pulp magazine publishing at the end of the 1930s. In 1941 the two magazines were combined into one, titled Future Fiction combined with Science Fiction, but in 1943 wartime paper shortages ended the magazine's run, as Louis Silberkleit, the publisher, decided to focus his resources on his mystery and western magazine titles. In 1950, with the market improving again, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction, still in the pulp format. In the mid-1950s he also relaunched Science Fiction, this time under the title Science Fiction Stories. Silberkleit kept both magazines on very slim budgets throughout the 1950s. In 1960 both titles ceased publication when their distributor suddenly dropped all of Silberkleit's titles.

Science Fiction Adventures was a British digest-size science fiction magazine, published from 1958 to 1963 by Nova Publications as a companion to New Worlds and Science Fantasy. It was edited by John Carnell. Science Fiction Adventures began as a reprint of the American magazine of the same name, Science Fiction Adventures, but after only three issues the American version ceased publication. Instead of closing down the British version, which had growing circulation, Nova decided to continue publishing it with new material. The fifth issue was the last which contained stories reprinted from the American magazine, though Carnell did occasionally reprint stories thereafter from other sources.

Uncanny Stories was a pulp magazine which published a single issue, dated April 1941. It was published by Abraham and Martin Goodman, who were better known for "weird-menace" pulp magazines that included much more sex in the fiction than was usual in science fiction of that era. The Goodmans published Marvel Science Stories from 1938 to 1941, and Uncanny Stories appeared just as Marvel Science Stories ceased publication, perhaps in order to use up the material in inventory acquired by Marvel Science Stories. The fiction was poor quality; the lead story, Ray Cummings' "Coming of the Giant Germs", has been described as "one of his most appalling stories".