Unknown was an American pulp fantasy fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1943 by Street & Smith, and edited by John W. Campbell. Unknown was a companion to Street & Smith's science fiction pulp, Astounding Science Fiction, which was also edited by Campbell at the time; many authors and illustrators contributed to both magazines. The leading fantasy magazine in the 1930s was Weird Tales, which focused on shock and horror. Campbell wanted to publish a fantasy magazine with more finesse and humor than Weird Tales, and put his plans into action when Eric Frank Russell sent him the manuscript of his novel Sinister Barrier, about aliens who own the human race. Unknown's first issue appeared in March 1939; in addition to Sinister Barrier, it included H. L. Gold's "Trouble With Water", a humorous fantasy about a New Yorker who meets a water gnome. Gold's story was the first of many in Unknown to combine commonplace reality with the fantastic.

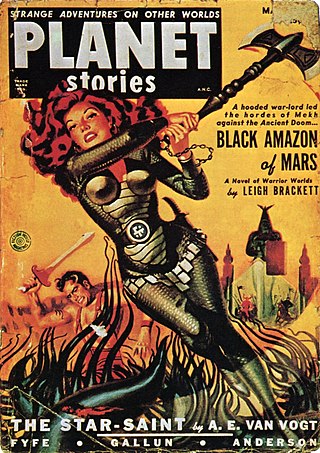

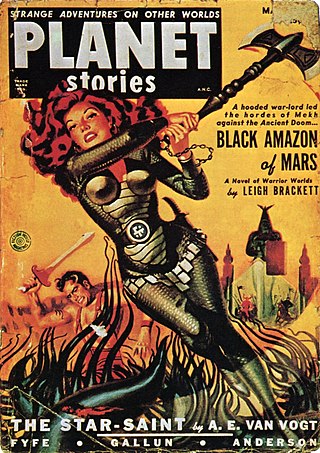

Planet Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published by Fiction House between 1939 and 1955. It featured interplanetary adventures, both in space and on some other planets, and was initially focused on a young readership. Malcolm Reiss was editor or editor-in-chief for all of its 71 issues. Planet Stories was launched at the same time as Planet Comics, the success of which probably helped to fund the early issues of Planet Stories. Planet Stories did not pay well enough to regularly attract the leading science fiction writers of the day, but occasionally obtained work from well-known authors, including Isaac Asimov and Clifford D. Simak. In 1952 Planet Stories published Philip K. Dick's first sale, and printed four more of his stories over the next three years.

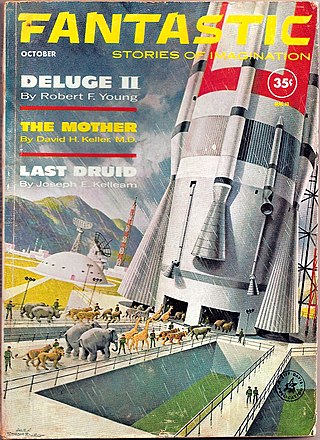

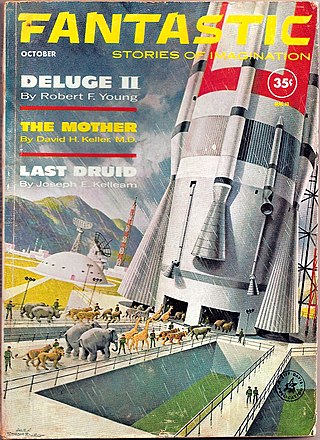

Fantastic was an American digest-size fantasy and science fiction magazine, published from 1952 to 1980. It was founded by the publishing company Ziff Davis as a fantasy companion to Amazing Stories. Early sales were good, and the company quickly decided to switch Amazing from pulp format to digest, and to cease publication of their other science fiction pulp, Fantastic Adventures. Within a few years sales fell, and Howard Browne, the editor, was forced to switch the focus to science fiction rather than fantasy. Browne lost interest in the magazine as a result and the magazine generally ran poor-quality fiction in the mid-1950s, under Browne and his successor, Paul W. Fairman.

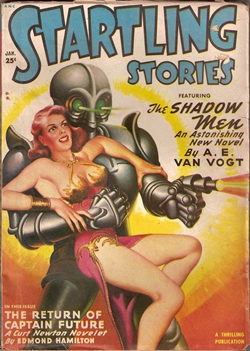

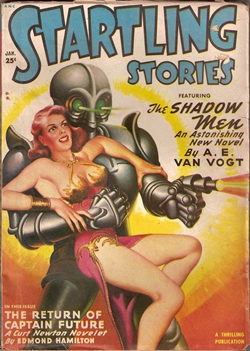

Startling Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1955 by publisher Ned Pines' Standard Magazines. It was initially edited by Mort Weisinger, who was also the editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories, Standard's other science fiction title. Startling ran a lead novel in every issue; the first was The Black Flame by Stanley G. Weinbaum. When Standard Magazines acquired Thrilling Wonder in 1936, it also gained the rights to stories published in that magazine's predecessor, Wonder Stories, and selections from this early material were reprinted in Startling as "Hall of Fame" stories. Under Weisinger the magazine focused on younger readers and, when Weisinger was replaced by Oscar J. Friend in 1941, the magazine became even more juvenile in focus, with clichéd cover art and letters answered by a "Sergeant Saturn". Friend was replaced by Sam Merwin Jr. in 1945, and Merwin was able to improve the quality of the fiction substantially, publishing Arthur C. Clarke's Against the Fall of Night, and several other well-received stories.

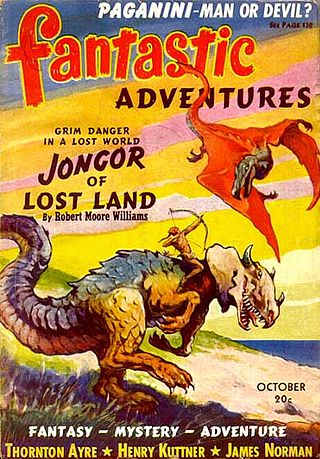

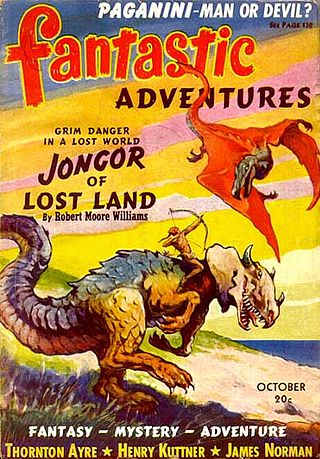

Fantastic Adventures was an American pulp fantasy and science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1953 by Ziff-Davis. It was initially edited by Raymond A. Palmer, who was also the editor of Amazing Stories, Ziff-Davis's other science fiction title. The first nine issues were in bedsheet format, but in June 1940 the magazine switched to a standard pulp size. It was almost cancelled at the end of 1940, but the October 1940 issue enjoyed unexpectedly good sales, helped by a strong cover by J. Allen St. John for Robert Moore Williams' Jongor of Lost Land. By May 1941 the magazine was on a regular monthly schedule. Historians of science fiction consider that Palmer was unable to maintain a consistently high standard of fiction, but Fantastic Adventures soon developed a reputation for light-hearted and whimsical stories. Much of the material was written by a small group of writers under both their own names and house names. The cover art, like those of many other pulps of the era, focused on beautiful women in melodramatic action scenes. One regular cover artist was H.W. McCauley, whose glamorous "MacGirl" covers were popular with the readers, though the emphasis on depictions of attractive and often partly clothed women did draw some objections.

Uncanny Tales was a Canadian science fiction pulp magazine edited by Melvin R. Colby that ran from November 1940 to September 1943. It was created in response to the wartime reduction of imports on British and American science-fiction pulp magazines. Initially it contained stories only from Canadian authors, with much of its contents supplied by Thomas P. Kelley, but within a few issues Colby began to obtain reprint rights to American stories from Donald A. Wollheim and Sam Moskowitz. Paper shortages eventually forced the magazine to shut down, and it is now extremely rare.

Scoops was a weekly British science fiction magazine published by Pearson's in tabloid format in 1934, edited by Haydn Dimmock. Scoops was launched as a boy's paper, and it was not until several issues had appeared that Dimmock discovered there was an adult audience for science fiction. Circulation was poor, and Dimmock attempted to change the magazine's focus to more mature material. He reprinted Arthur Conan Doyle's The Poison Belt, improved the cover art, and obtained fiction from British science fiction writers such as John Russell Fearn and Maurice Hugi, but to no avail. Pearson's cancelled the magazine because of poor sales; the twentieth issue, dated 23 June 1934, was the last. The failure of the magazine contributed to the belief that Britain could not support a science fiction magazine, and it was not until 1937, with Tales of Wonder, that another attempt was made.

Science Fiction Quarterly was an American pulp science fiction magazine that was published from 1940 to 1943 and again from 1951 to 1958. Charles Hornig served as editor for the first two issues; Robert A. W. Lowndes edited the remainder. Science Fiction Quarterly was launched by publisher Louis Silberkleit during a boom in science fiction magazines at the end of the 1930s. Silberkleit launched two other science fiction titles at about the same time: all three ceased publication before the end of World War II, falling prey to slow sales and paper shortages. In 1950 and 1951, as the market improved, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction and Science Fiction Quarterly. By the time Science Fiction Quarterly ceased publication in 1958, it was the last surviving science fiction pulp magazine, all other survivors having changed to different formats.

Science-Fiction Plus was an American science fiction magazine published by Hugo Gernsback for seven issues in 1953. In 1926, Gernsback had launched Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine, but he had not been involved in the genre since 1936, when he sold Wonder Stories. Science-Fiction Plus was initially in slick format, meaning that it was large-size and printed on glossy paper. Gernsback had always believed in the educational power of science fiction, and he continued to advocate his views in the new magazine's editorials. The managing editor, Sam Moskowitz, had been a reader of the early pulp magazines, and published many writers who had been popular before World War II, such as Raymond Z. Gallun, Eando Binder, and Harry Bates. Combined with Gernsback's earnest editorials, the use of these early writers gave the magazine an anachronistic feel.

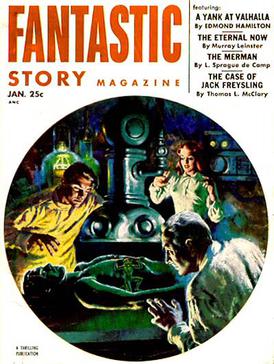

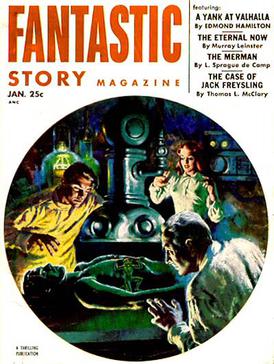

Fantastic Story Quarterlywas a pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1950 to 1955 by Best Books, a subsidiary imprint of Standard Magazines, based in Kokomo, Indiana. The name was changed with the Summer 1951 issue to Fantastic Story Magazine. It was launched to reprint stories from the early years of the science fiction pulp magazines, and was initially intended to carry no new fiction, though in the end every issue contained at least one new story. It was sufficiently successful for Standard to launch Wonder Story Annual as a vehicle for more science fiction reprints, but the success did not last. In 1955 it was merged with Standard's Startling Stories. Original fiction in Fantastic Story included Gordon R. Dickson's first sale, "Trespass", and stories by Walter M. Miller and Richard Matheson.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries was an American science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine published from 1939 to 1953. The editor was Mary Gnaedinger. It was launched by the Munsey Company as a way to reprint the many science fiction and fantasy stories which had appeared over the preceding decades in Munsey magazines such as Argosy. From its first issue, dated September/October 1939, Famous Fantastic Mysteries was an immediate success. Less than a year later, a companion magazine, Fantastic Novels, was launched.

Future Science Fiction and Science Fiction Stories were two American science fiction magazines that were published under various names between 1939 and 1943 and again from 1950 to 1960. Both publications were edited by Charles Hornig for the first few issues; Robert W. Lowndes took over in late 1941 and remained editor until the end. The initial launch of the magazines came as part of a boom in science fiction pulp magazine publishing at the end of the 1930s. In 1941 the two magazines were combined into one, titled Future Fiction combined with Science Fiction, but in 1943 wartime paper shortages ended the magazine's run, as Louis Silberkleit, the publisher, decided to focus his resources on his mystery and western magazine titles. In 1950, with the market improving again, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction, still in the pulp format. In the mid-1950s he also relaunched Science Fiction, this time under the title Science Fiction Stories. Silberkleit kept both magazines on very slim budgets throughout the 1950s. In 1960 both titles ceased publication when their distributor suddenly dropped all of Silberkleit's titles.

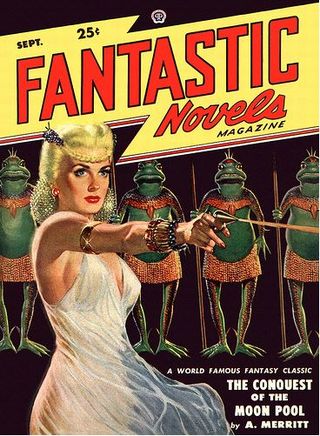

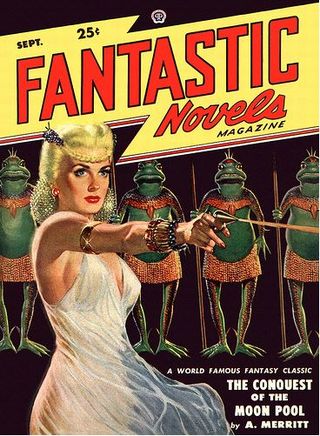

Fantastic Novels was an American science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine published by the Munsey Company of New York from 1940 to 1941, and again by Popular Publications, also of New York, from 1948 to 1951. It was a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Like that magazine, it mostly reprinted science fiction and fantasy classics from earlier decades, such as novels by A. Merritt, George Allan England, and Victor Rousseau, though it occasionally published reprints of more recent work, such as Earth's Last Citadel, by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore.

Marvel Science Stories was an American pulp magazine that ran for a total of fifteen issues in two separate runs, both edited by Robert O. Erisman. The publisher for the first run was Postal Publications, and the second run was published by Western Publishing; both companies were owned by Abraham and Martin Goodman. The first issue was dated August 1938, and carried stories with more sexual content than was usual for the genre, including several stories by Henry Kuttner, under his own name and also under pseudonyms. Reaction was generally negative, with one reader referring to Kuttner's story "The Time Trap" as "trash". This was the first of several titles featuring the word "Marvel", and Marvel Comics came from the same stable in the following year.

Fantasy was a British pulp science fiction magazine which published three issues in London between 1938 and 1939. The editor was T. Stanhope Sprigg; when the war started, he enlisted in the RAF and the magazine was closed down. The publisher, George Newnes Ltd, paid respectable rates, and as a result Sprigg was able to obtain some good quality material, including stories by John Wyndham, Eric Frank Russell, and John Russell Fearn.

Captain Future was a science fiction pulp magazine launched in 1940 by Better Publications, and edited initially by Mort Weisinger. It featured the adventures of Captain Future, a super-scientist whose real name was Curt Newton, in every issue. All but two of the novels in the magazine were written by Edmond Hamilton; the other two were by Joseph Samachson. The magazine also published other stories that had nothing to do with the title character, including Fredric Brown's first science fiction sale, "Not Yet the End". Captain Future published unabashed space opera, and was, in the words of science fiction historian Mike Ashley, "perhaps the most juvenile" of the science fiction pulps to appear in the early years of World War II. Wartime paper shortages eventually led to the magazine's cancellation: the last issue was dated Spring 1944.

Scientific Detective Monthly was a pulp magazine that published fifteen issues beginning in January 1930. It was launched by Hugo Gernsback as part of his second venture into science-fiction magazine publishing, and was intended to focus on detective and mystery stories with a scientific element. Many of the stories involved contemporary science without any imaginative elements—for example, a story in the first issue turned on the use of a bolometer to detect a black girl blushing—but there were also one or two science fiction stories in every issue.

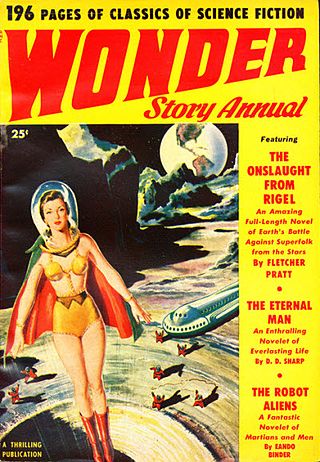

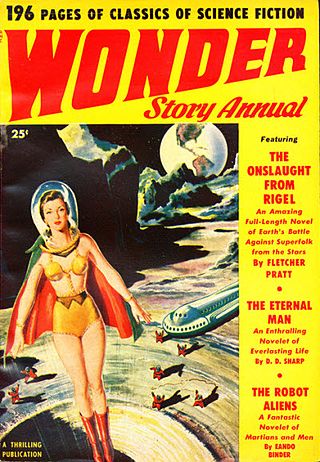

Wonder Story Annual was a science fiction pulp magazine which was launched in 1950 by Standard Magazines. It was created as a vehicle to reprint stories from early issues of Wonder Stories, Startling Stories, and Wonder Stories Quarterly, which were owned by the same publisher. It lasted for four issues, succumbing in 1953 to competition from the growing market for paperback science fiction. Reprinted stories included Twice in Time, by Manly Wade Wellman, and "The Brain-Stealers of Mars", by John W. Campbell.

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.

Fantasy was a British science fiction magazine, edited by Walter Gillings, which published three issues from 1946 to 1947. Gillings began collecting submissions for the magazine in 1943, but the publisher, Temple Bar, delayed launching it until the success of New Worlds, another British science fiction magazine, convinced them there was a viable market. Gillings obtained stories from Eric Frank Russell, John Russell Fearn, and Arthur C. Clarke, whose "Technical Error" was the first story of Clarke's to see print in the UK. Gillings published two more stories by Clarke, both under pseudonyms, but Temple Bar ceased publication of Fantasy after the third issue because of paper rationing caused by World War II. Gillings was able to use some of the stories he had acquired for Fantasy in 1950, when he became editor of Science Fantasy.