Weird Tales is an American fantasy and horror fiction pulp magazine founded by J. C. Henneberger and J. M. Lansinger in late 1922. The first issue, dated March 1923, appeared on newsstands February 18. The first editor, Edwin Baird, printed early work by H. P. Lovecraft, Seabury Quinn, and Clark Ashton Smith, all of whom went on to be popular writers, but within a year, the magazine was in financial trouble. Henneberger sold his interest in the publisher, Rural Publishing Corporation, to Lansinger, and refinanced Weird Tales, with Farnsworth Wright as the new editor. The first issue under Wright's control was dated November 1924. The magazine was more successful under Wright, and despite occasional financial setbacks, it prospered over the next 15 years. Under Wright's control, the magazine lived up to its subtitle, "The Unique Magazine", and published a wide range of unusual fiction.

Amazing Stories is an American science fiction magazine launched in April 1926 by Hugo Gernsback's Experimenter Publishing. It was the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction. Science fiction stories had made regular appearances in other magazines, including some published by Gernsback, but Amazing helped define and launch a new genre of pulp fiction.

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is a U.S. fantasy and science-fiction magazine, first published in 1949 by Mystery House, a subsidiary of Lawrence Spivak's Mercury Press. Editors Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas had approached Spivak in the mid-1940s about creating a fantasy companion to Spivak's existing mystery title, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. The first issue was titled The Magazine of Fantasy, but the decision was quickly made to include science fiction as well as fantasy, and the title was changed correspondingly with the second issue. F&SF was quite different in presentation from the existing science-fiction magazines of the day, most of which were in pulp format: it had no interior illustrations, no letter column, and text in a single-column format, which in the opinion of science-fiction historian Mike Ashley "set F&SF apart, giving it the air and authority of a superior magazine".

Unknown was an American pulp fantasy fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1943 by Street & Smith, and edited by John W. Campbell. Unknown was a companion to Street & Smith's science fiction pulp, Astounding Science Fiction, which was also edited by Campbell at the time; many authors and illustrators contributed to both magazines. The leading fantasy magazine in the 1930s was Weird Tales, which focused on shock and horror. Campbell wanted to publish a fantasy magazine with more finesse and humor than Weird Tales, and put his plans into action when Eric Frank Russell sent him the manuscript of his novel Sinister Barrier, about aliens who own the human race. Unknown's first issue appeared in March 1939; in addition to Sinister Barrier, it included H. L. Gold's "Trouble With Water", a humorous fantasy about a New Yorker who meets a water gnome. Gold's story was the first of many in Unknown to combine commonplace reality with the fantastic.

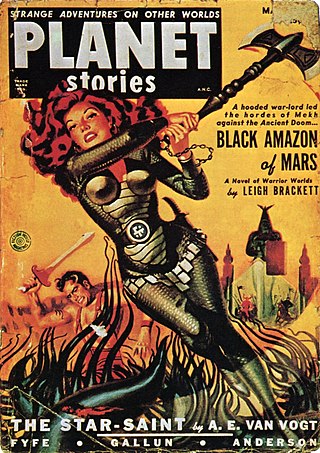

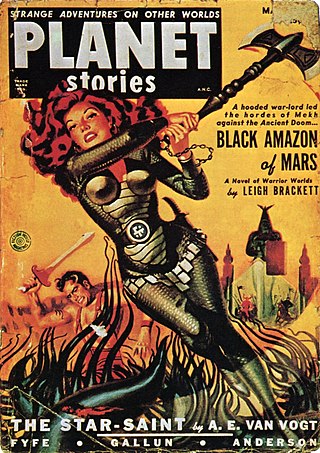

Planet Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published by Fiction House between 1939 and 1955. It featured interplanetary adventures, both in space and on some other planets, and was initially focused on a young readership. Malcolm Reiss was editor or editor-in-chief for all of its 71 issues. Planet Stories was launched at the same time as Planet Comics, the success of which probably helped to fund the early issues of Planet Stories. Planet Stories did not pay well enough to regularly attract the leading science fiction writers of the day, but occasionally obtained work from well-known authors, including Isaac Asimov and Clifford D. Simak. In 1952 Planet Stories published Philip K. Dick's first sale, and printed four more of his stories over the next three years.

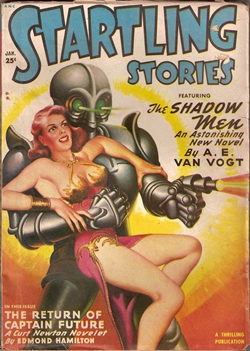

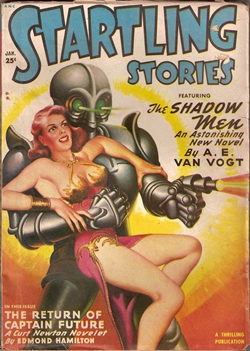

Startling Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1955 by publisher Ned Pines' Standard Magazines. It was initially edited by Mort Weisinger, who was also the editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories, Standard's other science fiction title. Startling ran a lead novel in every issue; the first was The Black Flame by Stanley G. Weinbaum. When Standard Magazines acquired Thrilling Wonder in 1936, it also gained the rights to stories published in that magazine's predecessor, Wonder Stories, and selections from this early material were reprinted in Startling as "Hall of Fame" stories. Under Weisinger the magazine focused on younger readers and, when Weisinger was replaced by Oscar J. Friend in 1941, the magazine became even more juvenile in focus, with clichéd cover art and letters answered by a "Sergeant Saturn". Friend was replaced by Sam Merwin Jr. in 1945, and Merwin was able to improve the quality of the fiction substantially, publishing Arthur C. Clarke's Against the Fall of Night, and several other well-received stories.

Robert Augustine Ward "Doc" Lowndes was an American science fiction author, editor and fan. He was known best as the editor of Future Science Fiction, Science Fiction, and Science Fiction Quarterly, among many other crime-fiction, western, sports-fiction, and other pulp and digest sized magazines for Columbia Publications. Among the most famous writers he was first to publish at Columbia was mystery writer Edward D. Hoch, who in turn would contribute to Lowndes's fiction magazines as long as he was editing them. Lowndes was a principal member of the Futurians. His first story, "The Outpost at Altark" for Super Science in 1940, was written in collaboration with fellow Futurian Donald A. Wollheim, uncredited.

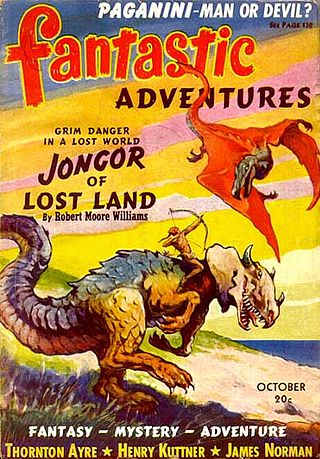

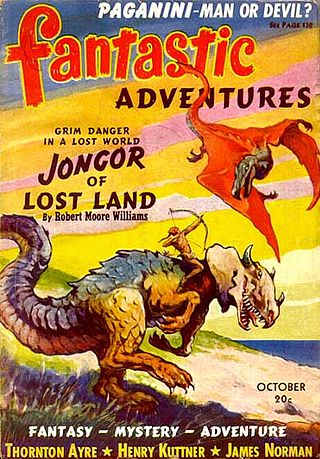

Fantastic Adventures was an American pulp fantasy and science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1953 by Ziff-Davis. It was initially edited by Raymond A. Palmer, who was also the editor of Amazing Stories, Ziff-Davis's other science fiction title. The first nine issues were in bedsheet format, but in June 1940 the magazine switched to a standard pulp size. It was almost cancelled at the end of 1940, but the October 1940 issue enjoyed unexpectedly good sales, helped by a strong cover by J. Allen St. John for Robert Moore Williams' Jongor of Lost Land. By May 1941 the magazine was on a regular monthly schedule. Historians of science fiction consider that Palmer was unable to maintain a consistently high standard of fiction, but Fantastic Adventures soon developed a reputation for light-hearted and whimsical stories. Much of the material was written by a small group of writers under both their own names and house names. The cover art, like those of many other pulps of the era, focused on beautiful women in melodramatic action scenes. One regular cover artist was H.W. McCauley, whose glamorous "MacGirl" covers were popular with the readers, though the emphasis on depictions of attractive and often partly clothed women did draw some objections.

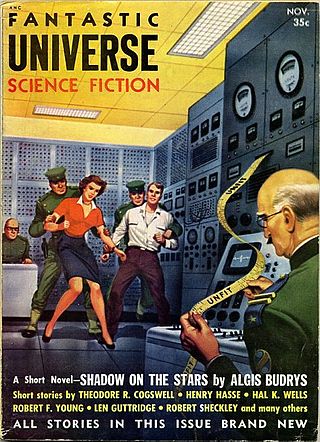

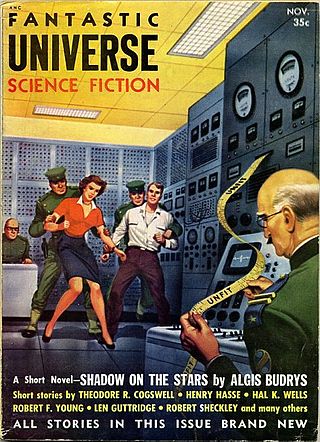

Fantastic Universe was a U.S. science fiction magazine which began publishing in the 1950s. It ran for 69 issues, from June 1953 to March 1960, under two different publishers. It was part of the explosion of science fiction magazine publishing in the 1950s in the United States, and was moderately successful, outlasting almost all of its competitors. The main editors were Leo Margulies (1954–1956) and Hans Stefan Santesson (1956–1960); under Santesson's tenure the quality declined somewhat, and the magazine became known for printing much UFO-related material. A collection of stories from the magazine, edited by Santesson, appeared in 1960 from Prentice-Hall, titled The Fantastic Universe Omnibus.

Super Science Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine published by Popular Publications from 1940 to 1943, and again from 1949 to 1951. Popular launched it under their Fictioneers imprint, which they used for magazines, paying writers less than one cent per word. Frederik Pohl was hired in late 1939, at 19 years old, to edit the magazine; he also edited Astonishing Stories, a companion science fiction publication. Pohl left in mid-1941 and Super Science Stories was given to Alden H. Norton to edit; a few months later Norton rehired Pohl as an assistant. Popular gave Pohl a very low budget, so most manuscripts submitted to Super Science Stories had already been rejected by the higher-paying magazines. This made it difficult to acquire good fiction, but Pohl was able to acquire stories for the early issues from the Futurians, a group of young science fiction fans and aspiring writers.

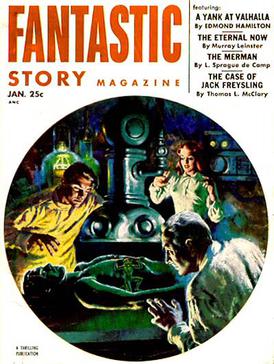

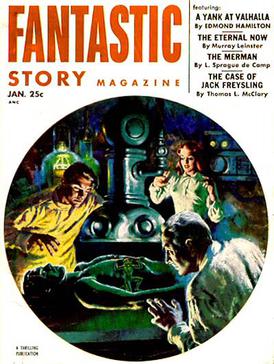

Fantastic Story Quarterlywas a pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1950 to 1955 by Best Books, a subsidiary imprint of Standard Magazines, based in Kokomo, Indiana. The name was changed with the Summer 1951 issue to Fantastic Story Magazine. It was launched to reprint stories from the early years of the science fiction pulp magazines, and was initially intended to carry no new fiction, though in the end every issue contained at least one new story. It was sufficiently successful for Standard to launch Wonder Story Annual as a vehicle for more science fiction reprints, but the success did not last. In 1955 it was merged with Standard's Startling Stories. Original fiction in Fantastic Story included Gordon R. Dickson's first sale, "Trespass", and stories by Walter M. Miller and Richard Matheson.

Satellite Science Fiction was an American science-fiction magazine published from October 1956 to April 1959 by Leo Margulies' Renown Publications. Initially, Satellite was digest sized and ran a full-length novel in each issue with a handful of short stories accompanying it. The policy was intended to help it compete against paperbacks, which were taking a growing share of the market. Sam Merwin edited the first two issues; Margulies took over when Merwin left and then hired Frank Belknap Long for the February 1959 issue. That issue saw the format change to letter size, in the hope that the magazine would be more prominent on newsstands. The experiment was a failure and Margulies closed the magazine when the sales figures came in.

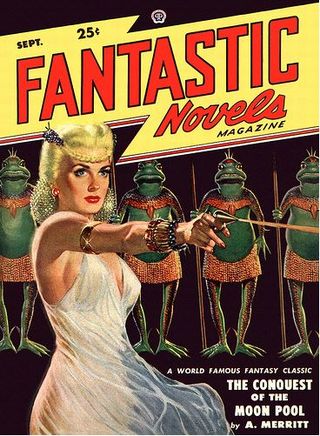

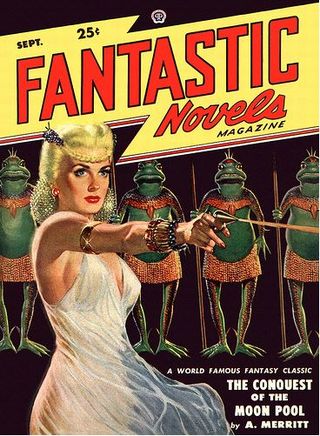

Fantastic Novels was an American science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine published by the Munsey Company of New York from 1940 to 1941, and again by Popular Publications, also of New York, from 1948 to 1951. It was a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Like that magazine, it mostly reprinted science fiction and fantasy classics from earlier decades, such as novels by A. Merritt, George Allan England, and Victor Rousseau, though it occasionally published reprints of more recent work, such as Earth's Last Citadel, by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore.

A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine was an American pulp magazine which published five issues from December 1949 to October 1950. It took its name from fantasy writer A. Merritt, who had died in 1943, and it aimed to capitalize on Merritt's popularity. It was published by Popular Publications, alternating months with Fantastic Novels, another title of theirs. It may have been edited by Mary Gnaedinger, who also edited Fantastic Novels and Famous Fantastic Mysteries. It was a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries, and like that magazine mostly reprinted science-fiction and fantasy classics from earlier decades.

Strange Stories was a pulp magazine which ran for thirteen issues from 1939 to 1941. It was edited by Mort Weisinger, who was not credited. Contributors included Robert Bloch, Eric Frank Russell, C. L. Moore, August Derleth, and Henry Kuttner. Strange Stories was a competitor to the established leader in weird fiction, Weird Tales. With the launch, also in 1939, of the well-received Unknown, Strange Stories was unable to compete. It ceased publication in 1941 when Weisinger left to edit Superman comic books.

Two Complete Science-Adventure Books was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published by Fiction House, which lasted for eleven issues between 1950 and 1954 as a companion to Planet Stories. Each issue carried two novels or long novellas. It was initially intended to carry only reprints, but soon began to publish original stories. Contributors included Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, and James Blish. The magazine folded in 1954, almost at the end of the pulp era.

Ghost Stories was an American pulp magazine that published 64 issues between 1926 and 1932. It was one of the earliest competitors to Weird Tales, the first magazine to specialize in the fantasy and occult fiction genre. It was a companion magazine to True Story and True Detective Stories, and focused almost entirely on stories about ghosts, many of which were written by staff writers but presented under pseudonyms as true confessions. These were often accompanied by faked photographs to make the stories appear more believable. Ghost Stories also had original and reprinted contributions, including works by Robert E. Howard, Carl Jacobi, and Frank Belknap Long. Among the reprints were Agatha Christie's "The Last Seance", several stories by H.G. Wells, and Charles Dickens's "The Signal-Man". Initially successful, the magazine began to lose readers and in 1930 was sold to Harold Hersey. Hersey was unable to reverse the magazine's decline, and publication of Ghost Stories ceased in early 1932.

Captain Future was a science fiction pulp magazine launched in 1940 by Better Publications, and edited initially by Mort Weisinger. It featured the adventures of Captain Future, a super-scientist whose real name was Curt Newton, in every issue. All but two of the novels in the magazine were written by Edmond Hamilton; the other two were by Joseph Samachson. The magazine also published other stories that had nothing to do with the title character, including Fredric Brown's first science fiction sale, "Not Yet the End". Captain Future published unabashed space opera, and was, in the words of science fiction historian Mike Ashley, "perhaps the most juvenile" of the science fiction pulps to appear in the early years of World War II. Wartime paper shortages eventually led to the magazine's cancellation: the last issue was dated Spring 1944.

Mary Catherine Gnaedinger was an American editor of science fiction and fantasy pulp magazines.

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.