Pulp magazines were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 until around 1955. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazines printed on higher-quality paper were called "glossies" or "slicks". The typical pulp magazine had 128 pages; it was 7 inches (18 cm) wide by 10 inches (25 cm) high, and 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) thick, with ragged, untrimmed edges. Pulps were the successors to the penny dreadfuls, dime novels, and short-fiction magazines of the 19th century.

Argosy was an American magazine, founded in 1882 as The Golden Argosy, a children's weekly, edited by Frank Munsey and published by E. G. Rideout. Munsey took over as publisher when Rideout went bankrupt in 1883, and after many struggles made the magazine profitable. He shortened the title to The Argosy in 1888 and targeted an audience of men and boys with adventure stories. In 1894 he switched it to a monthly schedule and in 1896 he eliminated all non-fiction and started using cheap pulp paper, making it the first pulp magazine. Circulation had reached half a million by 1907, and remained strong until the 1930s. The name was changed to Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1920 after the magazine merged with All-Story Weekly, another Munsey pulp, and from 1929 it became just Argosy.

Popular Publications was one of the largest publishers of pulp magazines during its existence, at one point publishing 42 different titles per month. Company titles included detective, adventure, romance, and Western fiction. They were also known for the several 'weird menace' titles. They also published several pulp hero or character pulps.

Oriental Stories, later retitled The Magic Carpet Magazine, was an American pulp magazine published by Popular Fiction Co., and edited by Farnsworth Wright. It was launched in 1930 under the title Oriental Stories as a companion to Popular Fiction's Weird Tales, and carried stories with far eastern settings, including some fantasy. Contributors included Robert E. Howard, Frank Owen, and E. Hoffman Price. The magazine was not successful, and in 1932 publication was paused after the Summer issue. It was relaunched in 1933 under the title The Magic Carpet Magazine, with an expanded editorial policy that now included any story set in an exotic location, including other planets.

Henry Steeger III was an American magazine editor and publisher.

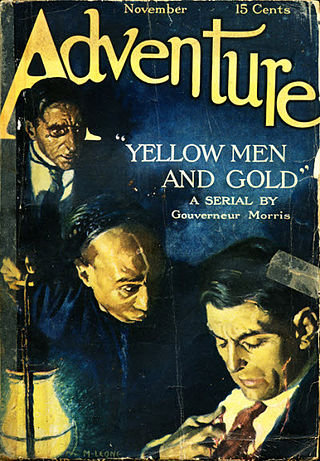

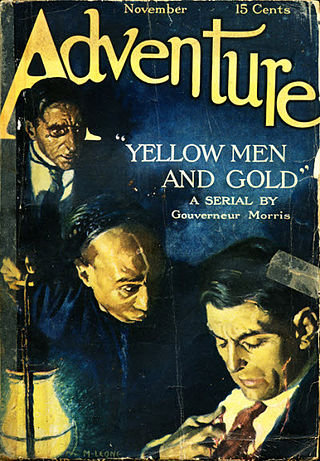

Adventure was an American pulp magazine that was first published in November 1910 by the Ridgway company, a subsidiary of the Butterick Publishing Company. Adventure went on to become one of the most profitable and critically acclaimed of all the American pulp magazines. The magazine had 881 issues. Its first editor was Trumbull White. He was succeeded in 1912 by Arthur Sullivant Hoffman (1876–1966), who edited the magazine until 1927.

Amazing Stories Annual was a pulp magazine which published a single issue in July 1927. It was edited by Hugo Gernsback, and featured the first publication of The Master Mind of Mars, by Edgar Rice Burroughs, which had been rejected by several other magazines, perhaps because the plot included a satire on religious fundamentalism. The other stories in Amazing Stories Annual were reprints, including two stories by A. Merritt, and one by H.G. Wells. The magazine sold out, and its success led Gernsback to launch Amazing Stories Quarterly the following year.

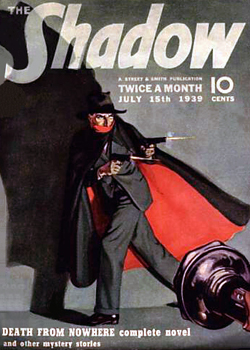

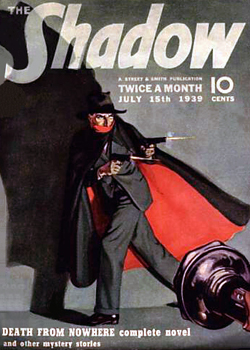

The Shadow was an American pulp magazine that was published by Street & Smith from 1931 to 1949. Each issue contained a novel about the Shadow, a mysterious crime-fighting figure who had been invented to narrate the introductions to radio broadcasts of stories from Street & Smith's Detective Story Magazine. A line from the introduction, "Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows", prompted listeners to ask at newsstands for the "Shadow magazine", which convinced the publisher that a magazine based around a single character could be successful. Walter Gibson persuaded the magazine's editor, Frank Blackwell, to let him write the first novel, The Living Shadow, which appeared in the first issue, dated April 1931.

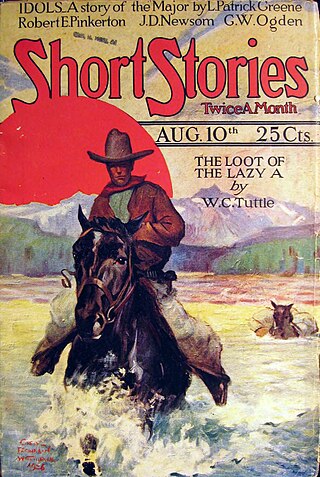

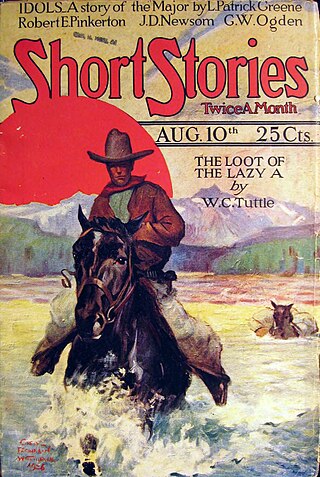

Short Stories was an American fiction magazine published between 1890 and 1959.

Robert Jasper Hogan (1897–1963) was an American writer, mainly of pulp fiction and later western fiction. He is notable as the creator of G-8, published by Popular Publications. Unlike other pulp authors, all his works appeared under his own name rather than house pseudonyms.

Doc Savage was an American pulp magazine that was published from 1933 to 1949 by Street & Smith. It was launched as a follow-up to the success of The Shadow, a magazine Street & Smith had started in 1931, based around a single character. Doc Savage's lead character, Clark Savage, was a scientist and adventurer, rather than purely a detective. Lester Dent was hired to write the lead novels, almost all of which were published under the house name "Kenneth Robeson". A few dozen novels were ghost-written by other writers, hired either by Dent or by Street & Smith. The magazine was successful, but was shut down in 1949 as part of Street & Smith's decision to abandon the pulp magazine field completely.

Ka-Zar was an American pulp magazine that published three issues in 1936 and 1937, edited by Martin Goodman. The lead character was modeled after Tarzan and the lead novel and short stories in each issue were adventures set in the jungle.

War Birds was a pulp magazine published by Dell from 1928 to 1937. It was the first pulp to focus on stories of war in the air, and soon had competitors. A series featuring fictional Irishman Terence X. O'Leary, which had started in other magazines, began to feature in War Birds in 1933, and in 1935 the magazine changed its name to Terence X. O'Leary's War Birds for three issues. In these issues the setting for stories about O'Leary changed from World War I to the near future; when the title changed back to War Birds later that year, the fiction reverted to ordinary aviation war stories for its last nine issues, including one final O'Leary story. The magazine's editors included Harry Steeger and Carson W. Mowre.

The Spider was an American pulp magazine published by Popular Publications from 1933 to 1943. Every issue included a lead novel featuring The Spider, a heroic crime-fighter. The magazine was intended as a rival to Street & Smith's The Shadow and Standard Magazine's The Phantom Detective, which also featured crime-fighting heroes. The novels in the first two issues were written by R. T. M. Scott; thereafter every lead novel was credited to "Grant Stockbridge", a house name. Norvell Page, a prolific pulp author, wrote most of these; almost all the rest were written by Emile Tepperman and A. H. Bittner. The novel in the final issue was written by Prentice Winchell.

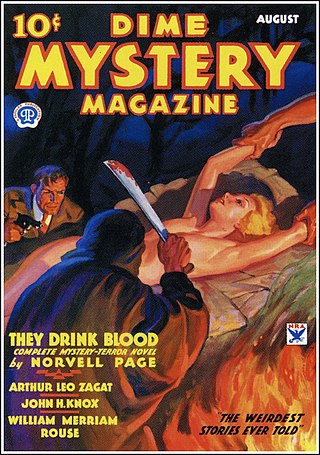

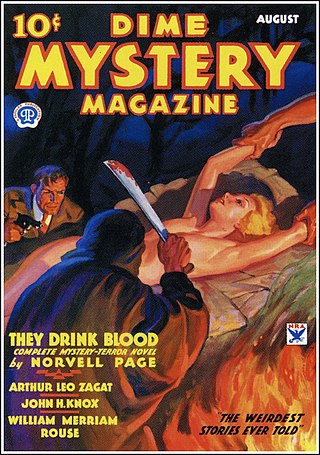

Dime Mystery Magazine was an American pulp magazine published from 1932 to 1950 by Popular Publications. Titled Dime Mystery Book Magazine during its first nine months, it contained ordinary mystery stories, including a full-length novel in each issue, but it was competing with Detective Novels Magazine and Detective Classics, two established magazines from a rival publisher, and failed to sell well. With the October 1933 issue the editorial policy changed, and it began publishing horror stories. Under the new policy, each story's protagonist had to struggle against something that appeared to be supernatural, but would eventually be revealed to have an everyday explanation. The new genre became known as "weird menace" fiction; the publisher, Harry Steeger, was inspired to create the new policy by the gory dramatizations he had seen at the Grand Guignol theater in Paris. Stories based on supernatural events were rare in Dime Mystery, but did occasionally appear.

The Western Raider was an American pulp magazine. The first issue was dated August/September 1938; it was followed by two more issues under that title, publishing Western fiction, and then was changed to a crime fiction pulp for two issues, titled The Octopus and The Scorpion. Both these two issues were named after a supervillain, rather than after a hero who fights crime, as was the case with most such magazines. Norvell Page wrote the lead novels for both the crime fiction issues; the second was rewritten by Ejler Jakobsson, one of the editors, to change the character from The Octopus to The Scorpion.

The Mysterious Wu Fang was a pulp magazine which published seven issues in 1935 and 1936. Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu, an oriental villain, was a "yellow peril" stereotype, and Popular Publications wanted to take advantage of the public's interest. The author of all seven lead novels was Robert J. Hogan, who was simultaneously writing the novels for G-8 and His Battle Aces, producing 130,000 to 150,000 words per month; Hogan was told not to rewrite, but to deliver his first drafts. The hero of the novels was a man named Val Kildare; other characters included a young assistant to Kildare, who was probably added to attract younger readers. The artist John Richard Flanagan, who had experience illustrating Fu Manchu, was hired, but in the opinion of pulp historian Robert Weinberg, "an imitation was an imitation, and the magazine did not sell well". There were short stories along with the lead novel in each issue, also with a "yellow peril" theme; the authors included Steve Fisher, Frank Gruber, O.B. Meyers, and Frank Beaston. The magazine was cancelled after seven issues in favor of a similar magazine with a different villain: Dr. Yen Sin. According to pulp historian Joseph Lewandowski, the decision to switch titles may have been because Wu Fang was too juvenile, and Dr. Yen Sin was supposed to be more mature.

Operator #5 was a pulp magazine published between 1934 and 1939.

Captain Zero was an American pulp magazine that published three issues in 1949 and 1950. The lead novels, written by G.T. Fleming-Roberts, featured Lee Allyn, who had been the subject of an experiment with radiation, and as a result was invisible between midnight and dawn. Under the name Captain Zero, Allyn became a vigilante, fighting crime at night. Allyn had no other superpowers, and the novels were straightforward mysteries in Weinberg's opinion, though pulp historian Robert Sampson considers them to be "complex...[they] pound along with hair-raising incidents..full of twists and high suspense". Captain Zero was the last crime-fighter hero magazine to be launched in the pulp era, ending an era that had begun with The Shadow in 1931. There was room in the magazine for only one or two short stories along with the lead novel; these were all straight mystery stories, without the veneer of science fiction of the Captain Zero novels.

Battle Birds was an American air-war pulp magazine, published by Popular Publications. It was launched at the end of 1932, but did not sell well, and in 1934 the publisher turned it into an air-war hero pulp titled Dusty Ayres and His Battle Birds. Robert Sidney Bowen, an established pulp writer, provided the lead novel each month, and also wrote the short stories that filled out the issue. Bowen's stories were set in the future, with the United States menaced by an Asian empire called the Black Invaders. The change was not successful enough to be extended beyond the initial plan of a year, and Bowen wrote a novel in which, unusually for pulp fiction, Dusty Ayres finally defeated the invaders, to end the series. The magazine ceased publication with the July/August 1935 issue. It restarted in 1940, under the original title, Battle Birds, and lasted for another four years. All the cover art was painted by Frederick Blakeslee.