Cyril M. Kornbluth was an American science fiction author and a member of the Futurians. He used a variety of pen-names, including Cecil Corwin, S. D. Gottesman, Edward J. Bellin, Kenneth Falconer, Walter C. Davies, Simon Eisner, Jordan Park, Arthur Cooke, Paul Dennis Lavond, and Scott Mariner.

Donald Allen Wollheim was an American science fiction editor, publisher, writer, and fan. As an author, he published under his own name as well as under pseudonyms, including David Grinnell, Martin Pearson, and Darrell G. Raynor. A founding member of the Futurians, he was a leading influence on science fiction development and fandom in the 20th-century United States. Ursula K. Le Guin called Wollheim "the tough, reliable editor of Ace Books, in the Late Pulpalignean Era, 1966 and '67", which is when he published her first two novels in Ace Double editions.

The Futurians were a group of science fiction fans, many of whom became editors and writers as well. The Futurians were based in New York City and were a major force in the development of science fiction writing and science fiction fandom in the years 1937–1945.

Frederik George Pohl Jr. was an American science-fiction writer, editor, and fan, with a career spanning nearly 75 years—from his first published work, the 1937 poem "Elegy to a Dead Satellite: Luna", to the 2011 novel All the Lives He Led.

James Benjamin Blish was an American science fiction and fantasy writer. He is best known for his Cities in Flight novels and his series of Star Trek novelizations written with his wife, J. A. Lawrence. His novel A Case of Conscience won the Hugo Award. He is credited with creating the term "gas giant" to refer to large planetary bodies.

Damon Francis Knight was an American science fiction author, editor, and critic. He is the author of "To Serve Man", a 1950 short story adapted for The Twilight Zone. He was married to fellow writer Kate Wilhelm.

Judith Josephine Grossman, who took the pen-name Judith Merril around 1945, was an American and then Canadian science fiction writer, editor and political activist, and one of the first women to be widely influential in those roles.

The Golden Age of Science Fiction, often identified in the United States as the years 1938–1946, was a period in which a number of foundational works of science fiction literature appeared. In the history of science fiction, the Golden Age follows the "pulp era" of the 1920s and 1930s, and precedes New Wave science fiction of the 1960s and 1970s. The 1950s are, in this scheme, a transitional period. Robert Silverberg, who came of age then, saw the 1950s as the true Golden Age.

Robert Augustine Ward "Doc" Lowndes was an American science fiction author, editor and fan. He was known best as the editor of Future Science Fiction, Science Fiction, and Science Fiction Quarterly, among many other crime-fiction, western, sports-fiction, and other pulp and digest sized magazines for Columbia Publications. Among the most famous writers he was first to publish at Columbia was mystery writer Edward D. Hoch, who in turn would contribute to Lowndes's fiction magazines as long as he was editing them. Lowndes was a principal member of the Futurians. His first story, "The Outpost at Altark" for Super Science in 1940, was written in collaboration with fellow Futurian Donald A. Wollheim, uncredited.

"The Secret Sense" is a science fiction short story by American writer Isaac Asimov, published in Cosmic Stories in March 1941. It takes place against the background of an ancient and highly developed culture living in large underground cities on Mars.

Super Science Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine published by Popular Publications from 1940 to 1943, and again from 1949 to 1951. Popular launched it under their Fictioneers imprint, which they used for magazines, paying writers less than one cent per word. Frederik Pohl was hired in late 1939, at 19 years old, to edit the magazine; he also edited Astonishing Stories, a companion science fiction publication. Pohl left in mid-1941 and Super Science Stories was given to Alden H. Norton to edit; a few months later Norton rehired Pohl as an assistant. Popular gave Pohl a very low budget, so most manuscripts submitted to Super Science Stories had already been rejected by the higher-paying magazines. This made it difficult to acquire good fiction, but Pohl was able to acquire stories for the early issues from the Futurians, a group of young science fiction fans and aspiring writers.

Uncanny Tales was a Canadian science fiction pulp magazine edited by Melvin R. Colby that ran from November 1940 to September 1943. It was created in response to the wartime reduction of imports on British and American science-fiction pulp magazines. Initially it contained stories only from Canadian authors, with much of its contents supplied by Thomas P. Kelley, but within a few issues Colby began to obtain reprint rights to American stories from Donald A. Wollheim and Sam Moskowitz. Wollheim's and Moskowitz's later accounts of the relationship with Colby differ. Moskowitz reported that he found out via an acquaintance of Wollheim's that Colby had been persuaded by Wollheim to stop buying Moskowitz's submissions. Paper shortages forced the magazine to shut down after less than three years. It is now extremely rare.

Science Fiction Quarterly was an American pulp science fiction magazine that was published from 1940 to 1943 and again from 1951 to 1958. Charles Hornig served as editor for the first two issues; Robert A. W. Lowndes edited the remainder. Science Fiction Quarterly was launched by publisher Louis Silberkleit during a boom in science fiction magazines at the end of the 1930s. Silberkleit launched two other science fiction titles at about the same time: all three ceased publication before the end of World War II, falling prey to slow sales and paper shortages. In 1950 and 1951, as the market improved, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction and Science Fiction Quarterly. By the time Science Fiction Quarterly ceased publication in 1958, it was the last surviving science fiction pulp magazine, all other survivors having changed to different formats.

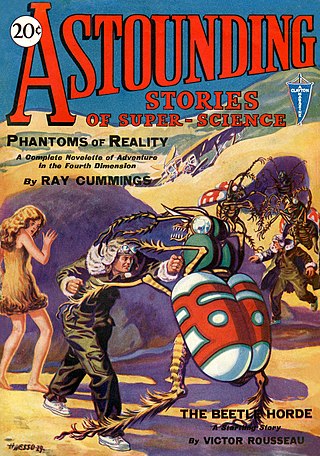

Analog Science Fiction and Fact is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science, the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William Clayton, and edited by Harry Bates. Clayton went bankrupt in 1933 and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The new editor was F. Orlin Tremaine, who soon made Astounding the leading magazine in the nascent pulp science fiction field, publishing well-regarded stories such as Jack Williamson's Legion of Space and John W. Campbell's "Twilight". At the end of 1937, Campbell took over editorial duties under Tremaine's supervision, and the following year Tremaine was let go, giving Campbell more independence. Over the next few years Campbell published many stories that became classics in the field, including Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, A. E. van Vogt's Slan, and several novels and stories by Robert A. Heinlein. The period beginning with Campbell's editorship is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction is a collection of critical essays by American writer Damon Knight. Most of the material in the original version of the book was originally published between 1952 and 1955 in various science fiction magazines including Infinity Science Fiction, Original SF Stories, and Future SF. The essays were highly influential, and contributed to Knight's stature as the foremost critic of science fiction of his generation. The book also constitutes an informal record of the "Boom Years" of science fiction from 1950 to 1955.

Astonishing Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published by Popular Publications between 1940 and 1943. It was founded under Popular's "Fictioneers" imprint, which paid lower rates than Popular's other magazines. The magazine's first editor was Frederik Pohl, who also edited a companion publication, Super Science Stories. After nine issues Pohl was replaced by Alden H. Norton, who subsequently rehired Pohl as an assistant. The budget for Astonishing was very low, which made it difficult to acquire good fiction, but through his membership in the Futurians, a group of young science fiction fans and aspiring writers, Pohl was able to find material to fill the early issues. The magazine was successful, and Pohl was able to increase his pay rates slightly within a year. He managed to obtain stories by writers who subsequently became very well known, such as Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein. After Pohl entered the army in early 1943, wartime paper shortages led Popular to cease publication of Astonishing. The final issue was dated April of that year.

Future Science Fiction and Science Fiction Stories were two American science fiction magazines that were published under various names between 1939 and 1943 and again from 1950 to 1960. Both publications were edited by Charles Hornig for the first few issues; Robert W. Lowndes took over in late 1941 and remained editor until the end. The initial launch of the magazines came as part of a boom in science fiction pulp magazine publishing at the end of the 1930s. In 1941 the two magazines were combined into one, titled Future Fiction combined with Science Fiction, but in 1943 wartime paper shortages ended the magazine's run, as Louis Silberkleit, the publisher, decided to focus his resources on his mystery and western magazine titles. In 1950, with the market improving again, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction, still in the pulp format. In the mid-1950s he also relaunched Science Fiction, this time under the title Science Fiction Stories. Silberkleit kept both magazines on very slim budgets throughout the 1950s. In 1960 both titles ceased publication when their distributor suddenly dropped all of Silberkleit's titles.

Comet was a pulp magazine which published five issues from December 1940 to July 1941. It was edited by F. Orlin Tremaine, who had edited Astounding Stories, one of the leaders of the science fiction magazine field, for several years in the mid-1930s. Tremaine paid one cent per word, which was higher than some of the competing magazines, but the publisher, H-K Publications based in Springfield, MA, was unable to sustain the magazine while it gained circulation, and it was cancelled after less than a year when Tremaine resigned. Comet published fiction by several well-known and popular writers, including E.E. Smith and Robert Moore Williams. The young Isaac Asimov, visiting Tremaine in Comet's offices, was alarmed when Tremaine asserted that anyone who gave stories to competing magazines for no pay should be blacklisted; Asimov promptly insisted that Donald Wollheim, to whom he had given a free story, should make him a token payment so he could say he had been paid.

Joseph Harold ("Harry") Dockweiler was a science-fiction author and literary agent. Dockweiler was best known by his pen name Dirk Wylie. Dockweiler was a member of The Futurians, a 1940s-era science-fiction fan community.

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.