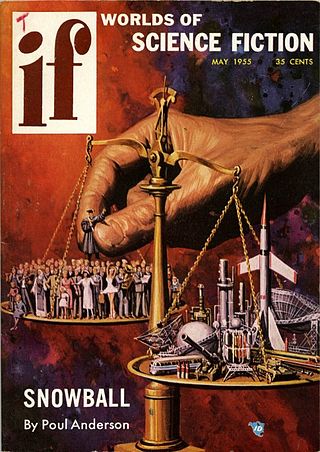

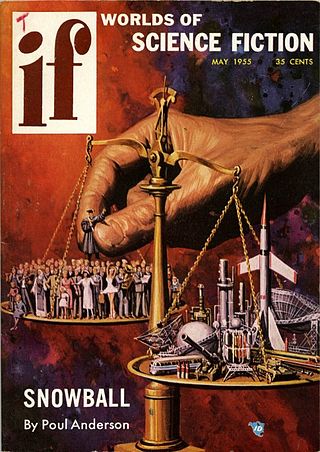

If was an American science fiction magazine launched in March 1952 by Quinn Publications, owned by James L. Quinn.

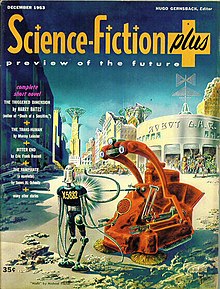

Amazing Stories is an American science fiction magazine launched in April 1926 by Hugo Gernsback's Experimenter Publishing. It was the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction. Science fiction stories had made regular appearances in other magazines, including some published by Gernsback, but Amazing helped define and launch a new genre of pulp fiction.

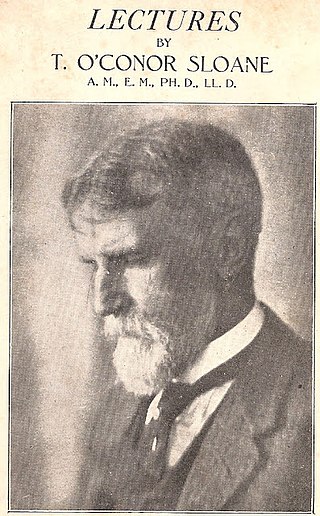

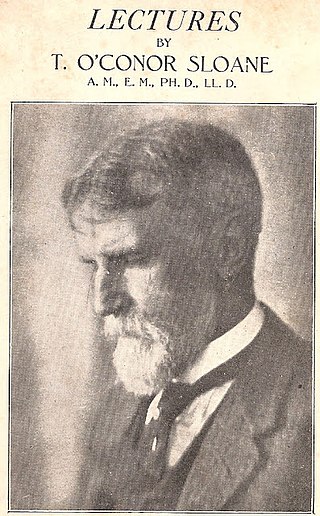

Thomas O'Conor Sloane was an American scientist, inventor, author, editor, educator, and linguist, perhaps best known for writing The Standard Electrical Dictionary and as the editor of Scientific American, from 1886 to 1896 and the first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, from 1929 to 1938.

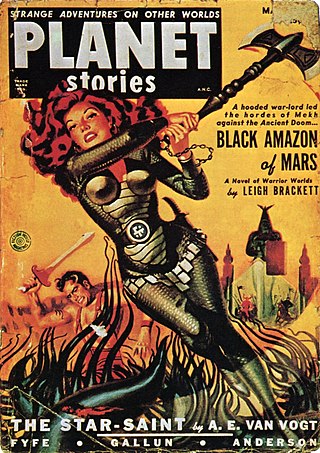

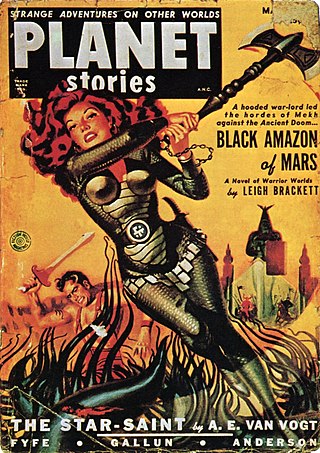

Planet Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published by Fiction House between 1939 and 1955. It featured interplanetary adventures, both in space and on some other planets, and was initially focused on a young readership. Malcolm Reiss was editor or editor-in-chief for all of its 71 issues. Planet Stories was launched at the same time as Planet Comics, the success of which probably helped to fund the early issues of Planet Stories. Planet Stories did not pay well enough to regularly attract the leading science fiction writers of the day, but occasionally obtained work from well-known authors, including Isaac Asimov and Clifford D. Simak. In 1952 Planet Stories published Philip K. Dick's first sale, and printed four more of his stories over the next three years.

Wonder Stories was an early American science fiction magazine which was published under several titles from 1929 to 1955. It was founded by Hugo Gernsback in 1929 after he had lost control of his first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, when his media company Experimenter Publishing went bankrupt. Within a few months of the bankruptcy, Gernsback launched three new magazines: Air Wonder Stories, Science Wonder Stories, and Science Wonder Quarterly.

Infinity Science Fiction was an American science fiction magazine, edited by Larry T. Shaw, and published by Royal Publications. The first issue, which appeared in November 1955, included Arthur C. Clarke's "The Star", a story about a planet destroyed by a nova that turns out to have been the Star of Bethlehem; it won the Hugo Award for that year. Shaw obtained stories from some of the leading writers of the day, including Brian Aldiss, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Sheckley, but the material was of variable quality. In 1958 Irwin Stein, the owner of Royal Publications, decided to shut down Infinity; the last issue was dated November 1958.

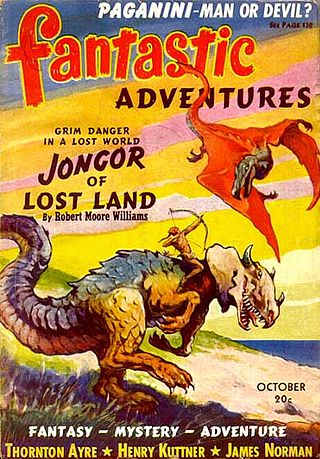

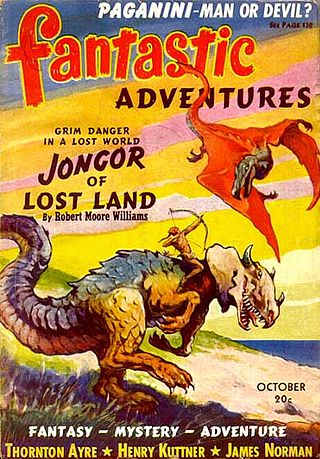

Fantastic Adventures was an American pulp fantasy and science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1953 by Ziff-Davis. It was initially edited by Raymond A. Palmer, who was also the editor of Amazing Stories, Ziff-Davis's other science fiction title. The first nine issues were in bedsheet format, but in June 1940 the magazine switched to a standard pulp size. It was almost cancelled at the end of 1940, but the October 1940 issue enjoyed unexpectedly good sales, helped by a strong cover by J. Allen St. John for Robert Moore Williams' Jongor of Lost Land. By May 1941 the magazine was on a regular monthly schedule. Historians of science fiction consider that Palmer was unable to maintain a consistently high standard of fiction, but Fantastic Adventures soon developed a reputation for light-hearted and whimsical stories. Much of the material was written by a small group of writers under both their own names and house names. The cover art, like those of many other pulps of the era, focused on beautiful women in melodramatic action scenes. One regular cover artist was H.W. McCauley, whose glamorous "MacGirl" covers were popular with the readers, though the emphasis on depictions of attractive and often partly clothed women did draw some objections.

Uncanny Tales was a Canadian science fiction pulp magazine edited by Melvin R. Colby that ran from November 1940 to September 1943. It was created in response to the wartime reduction of imports on British and American science-fiction pulp magazines. Initially it contained stories only from Canadian authors, with much of its contents supplied by Thomas P. Kelley, but within a few issues Colby began to obtain reprint rights to American stories from Donald A. Wollheim and Sam Moskowitz. Paper shortages eventually forced the magazine to shut down, and it is now extremely rare.

Science Fiction Quarterly was an American pulp science fiction magazine that was published from 1940 to 1943 and again from 1951 to 1958. Charles Hornig served as editor for the first two issues; Robert A. W. Lowndes edited the remainder. Science Fiction Quarterly was launched by publisher Louis Silberkleit during a boom in science fiction magazines at the end of the 1930s. Silberkleit launched two other science fiction titles at about the same time: all three ceased publication before the end of World War II, falling prey to slow sales and paper shortages. In 1950 and 1951, as the market improved, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction and Science Fiction Quarterly. By the time Science Fiction Quarterly ceased publication in 1958, it was the last surviving science fiction pulp magazine, all other survivors having changed to different formats.

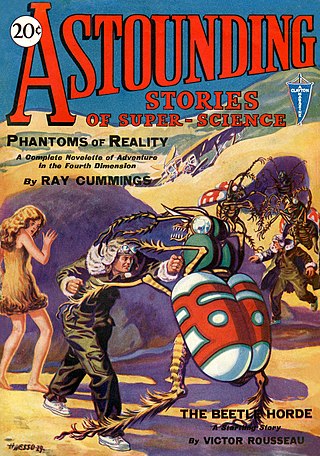

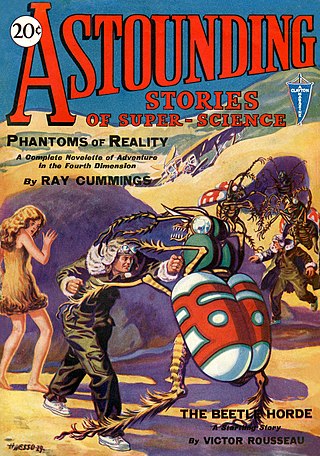

Analog Science Fiction and Fact is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science, the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William Clayton, and edited by Harry Bates. Clayton went bankrupt in 1933 and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The new editor was F. Orlin Tremaine, who soon made Astounding the leading magazine in the nascent pulp science fiction field, publishing well-regarded stories such as Jack Williamson's Legion of Space and John W. Campbell's "Twilight". At the end of 1937, Campbell took over editorial duties under Tremaine's supervision, and the following year Tremaine was let go, giving Campbell more independence. Over the next few years Campbell published many stories that became classics in the field, including Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, A. E. van Vogt's Slan, and several novels and stories by Robert A. Heinlein. The period beginning with Campbell's editorship is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

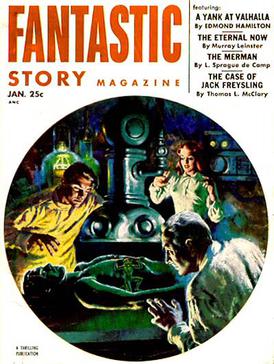

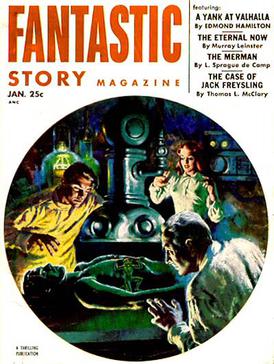

Fantastic Story Quarterlywas a pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1950 to 1955 by Best Books, a subsidiary imprint of Standard Magazines, based in Kokomo, Indiana. The name was changed with the Summer 1951 issue to Fantastic Story Magazine. It was launched to reprint stories from the early years of the science fiction pulp magazines, and was initially intended to carry no new fiction, though in the end every issue contained at least one new story. It was sufficiently successful for Standard to launch Wonder Story Annual as a vehicle for more science fiction reprints, but the success did not last. In 1955 it was merged with Standard's Startling Stories. Original fiction in Fantastic Story included Gordon R. Dickson's first sale, "Trespass", and stories by Walter M. Miller and Richard Matheson.

Future Science Fiction and Science Fiction Stories were two American science fiction magazines that were published under various names between 1939 and 1943 and again from 1950 to 1960. Both publications were edited by Charles Hornig for the first few issues; Robert W. Lowndes took over in late 1941 and remained editor until the end. The initial launch of the magazines came as part of a boom in science fiction pulp magazine publishing at the end of the 1930s. In 1941 the two magazines were combined into one, titled Future Fiction combined with Science Fiction, but in 1943 wartime paper shortages ended the magazine's run, as Louis Silberkleit, the publisher, decided to focus his resources on his mystery and western magazine titles. In 1950, with the market improving again, Silberkleit relaunched Future Fiction, still in the pulp format. In the mid-1950s he also relaunched Science Fiction, this time under the title Science Fiction Stories. Silberkleit kept both magazines on very slim budgets throughout the 1950s. In 1960 both titles ceased publication when their distributor suddenly dropped all of Silberkleit's titles.

Comet was a pulp magazine which published five issues from December 1940 to July 1941. It was edited by F. Orlin Tremaine, who had edited Astounding Stories, one of the leaders of the science fiction magazine field, for several years in the mid-1930s. Tremaine paid one cent per word, which was higher than some of the competing magazines, but the publisher, H-K Publications based in Springfield, MA, was unable to sustain the magazine while it gained circulation, and it was cancelled after less than a year when Tremaine resigned. Comet published fiction by several well-known and popular writers, including E.E. Smith and Robert Moore Williams. The young Isaac Asimov, visiting Tremaine in Comet's offices, was alarmed when Tremaine asserted that anyone who gave stories to competing magazines for no pay should be blacklisted; Asimov promptly insisted that Donald Wollheim, to whom he had given a free story, should make him a token payment so he could say he had been paid.

Captain Future was a science fiction pulp magazine launched in 1940 by Better Publications, and edited initially by Mort Weisinger. It featured the adventures of Captain Future, a super-scientist whose real name was Curt Newton, in every issue. All but two of the novels in the magazine were written by Edmond Hamilton; the other two were by Joseph Samachson. The magazine also published other stories that had nothing to do with the title character, including Fredric Brown's first science fiction sale, "Not Yet the End". Captain Future published unabashed space opera, and was, in the words of science fiction historian Mike Ashley, "perhaps the most juvenile" of the science fiction pulps to appear in the early years of World War II. Wartime paper shortages eventually led to the magazine's cancellation: the last issue was dated Spring 1944.

Scientific Detective Monthly was a pulp magazine that published fifteen issues beginning in January 1930. It was launched by Hugo Gernsback as part of his second venture into science-fiction magazine publishing, and was intended to focus on detective and mystery stories with a scientific element. Many of the stories involved contemporary science without any imaginative elements—for example, a story in the first issue turned on the use of a bolometer to detect a black girl blushing—but there were also one or two science fiction stories in every issue.

Flash Gordon Strange Adventure Magazine was a pulp magazine which was launched in December 1936. It was published by Harold Hersey, and was an attempt to cash in on the growing comics boom, and the popularity of the Flash Gordon comic strip in particular. The magazine contained a novel about Flash Gordon and three unrelated stories; there were also eight full-page color illustrations. The quality of both the artwork and the fiction was low, and the magazine only saw a single issue. It is now extremely rare.

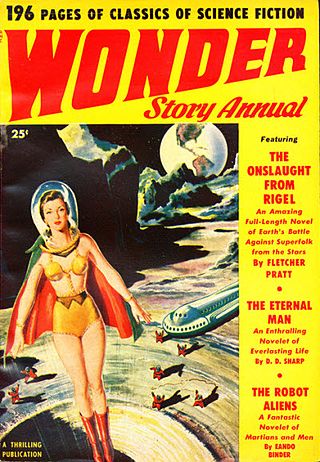

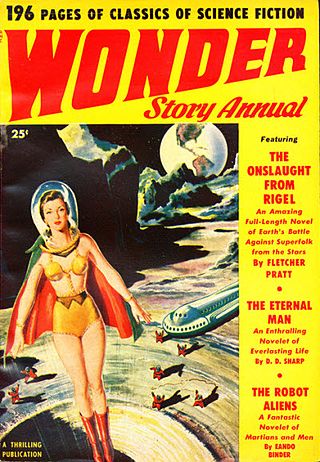

Wonder Story Annual was a science fiction pulp magazine which was launched in 1950 by Standard Magazines. It was created as a vehicle to reprint stories from early issues of Wonder Stories, Startling Stories, and Wonder Stories Quarterly, which were owned by the same publisher. It lasted for four issues, succumbing in 1953 to competition from the growing market for paperback science fiction. Reprinted stories included Twice in Time, by Manly Wade Wellman, and "The Brain-Stealers of Mars", by John W. Campbell.

Science-fiction and fantasy magazines began to be published in the United States in the 1920s. Stories with science-fiction themes had been appearing for decades in pulp magazines such as Argosy, but there were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith, one of the major pulp publishers, brought out Detective Story Magazine. The first magazine to focus solely on fantasy and horror was Weird Tales, which was launched in 1923, and established itself as the leading weird fiction magazine over the next two decades; writers such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard became regular contributors. In 1926 Weird Tales was joined by Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback; Amazing printed only science fiction, and no fantasy. Gernsback included a letter column in Amazing Stories, and this led to the creation of organized science-fiction fandom, as fans contacted each other using the addresses published with the letters. Gernsback wanted the fiction he printed to be scientifically accurate, and educational, as well as entertaining, but found it difficult to obtain stories that met his goals; he printed "The Moon Pool" by Abraham Merritt in 1927, despite it being completely unscientific. Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929, but quickly started several new magazines. Wonder Stories, one of Gernsback's titles, was edited by David Lasser, who worked to improve the quality of the fiction he received. Another early competitor was Astounding Stories of Super-Science, which appeared in 1930, edited by Harry Bates, but Bates printed only the most basic adventure stories with minimal scientific content, and little of the material from his era is now remembered.

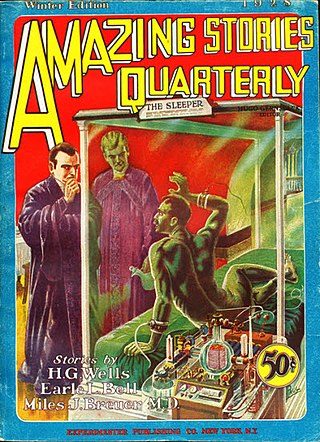

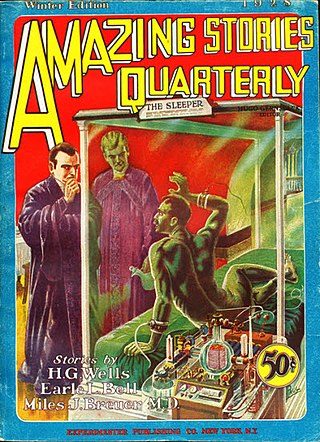

Amazing Stories Quarterly was a U.S. science fiction pulp magazine that was published between 1928 and 1934. It was launched by Hugo Gernsback as a companion to his Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine, which had begun publishing in April 1926. Amazing Stories had been successful enough for Gernsback to try a single issue of an Amazing Stories Annual in 1927, which had sold well, and he decided to follow it up with a quarterly magazine. The first issue of Amazing Stories Quarterly was dated Winter 1928 and carried a reprint of the 1899 version of H.G. Wells' When the Sleeper Wakes. Gernsback's policy of running a novel in each issue was popular with his readership, though the choice of Wells' novel was less so. Over the next five issues, only one more reprint appeared: Gernsback's own novel Ralph 124C 41+, in the Winter 1929 issue. Gernsback went bankrupt in early 1929, and lost control of both Amazing Stories and Amazing Stories Quarterly; associate editor T. O'Conor Sloane then took over as editor. The magazine began to run into financial difficulties in 1932, and the schedule became irregular; the last issue was dated Fall 1934.

Marvel Tales and Unusual Stories were two related American semi-professional science fiction magazines published in 1934 and 1935 by William L. Crawford. Crawford was a science fiction fan who believed that the pulp magazines of the time were too limited in what they would publish. In 1933, he distributed a flyer announcing Unusual Stories, and declaring that no taboos would prevent him from publishing worthwhile fiction. The flyer included a page from P. Schuyler Miller's "The Titan", which Miller had been unable to sell to the professional magazines because of its sexual content. A partial issue of Unusual Stories was distributed in early 1934, but Crawford then launched a new title, Marvel Tales, in May 1934. A total of five issues of Marvel Tales and three of Unusual Stories appeared over the next two years.