The House of Palaiologos, also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greek noble family that rose to power and produced the last and longest-ruling dynasty in the history of the Byzantine Empire. Their rule as Emperors and Autocrats of the Romans lasted almost two hundred years, from 1259 to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

The parish of Saint John is a parish of Barbados on the eastern side of the island. It is home to one of its secondary schools, The Lodge School. It is home to the St. John's Parish Church, which has a scenic view of the Atlantic Ocean from its perch near Hackleton's Cliff, which overlooks the East Coast of the island. In its southeastern corner, the shoreline turns northward, forming the small Conset Bay.

Thomas Palaiologos was Despot of the Morea from 1428 until the fall of the despotate in 1460, although he continued to claim the title until his death five years later. He was the younger brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine emperor. Thomas was appointed as Despot of the Morea by his oldest brother, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, in 1428, joining his two brothers and other despots Theodore and Constantine, already governing the Morea. Though Theodore proved reluctant to cooperate with his brothers, Thomas and Constantine successfully worked to strengthen the despotate and expand its borders. In 1432, Thomas brought the remaining territories of the Latin Principality of Achaea, established during the Fourth Crusade more than two hundred years earlier, into Byzantine hands by marrying Catherine Zaccaria, heiress to the principality.

Sir John Colleton, 1st Baronet (1608–1666) served King Charles I during the English Civil War. He rose through the Royalist ranks during the conflict, but later had his land-holdings seized when the Cavaliers were finally defeated by Parliamentary forces. Following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, he was one of eight individuals rewarded with grants of land in Carolina by King Charles II for having supported his efforts to regain the throne.

Andreas Palaiologos, sometimes anglicized to Andrew Palaeologus, was the eldest son of Thomas Palaiologos, Despot of the Morea. Thomas was a brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine emperor. After his father's death in 1465, Andreas was recognized as the titular Despot of the Morea and from 1483 onwards, he also claimed the title "Emperor of Constantinople".

Manuel Palaiologos was the youngest son of Thomas Palaiologos, a brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine emperor. Thomas took Manuel and the rest of his family to Corfu after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the subsequent Ottoman invasion of the Morea in 1460. After Thomas's death in 1465, the children moved to Rome, where they were initially taken care of by Cardinal Bessarion and were provided with money and housing by the papacy.

Colonel Sir Thomas Modyford, 1st Baronet was a planter of Barbados and Governor of Jamaica from 1664 to 1671.

Landulph is a hamlet and a rural civil parish in south-east Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is about 3 miles (5 km) north of Saltash in the St Germans Registration District.

George Mouzalon was a high official of the Empire of Nicaea under Theodore II Laskaris.

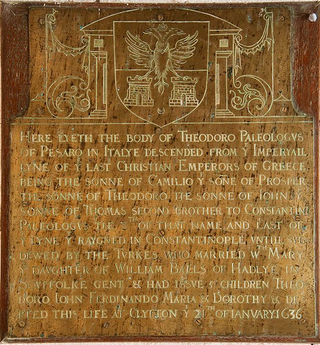

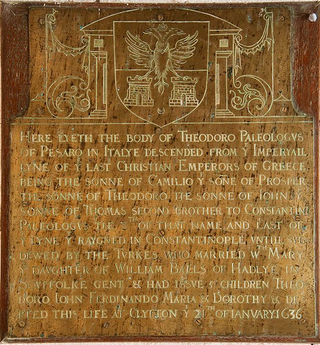

Theodore Paleologus was a 16th and 17th-century Greek nobleman, soldier and assassin. According to the genealogy presented on Theodore's tombstone, he was a direct male-line descendant of the Palaiologos dynasty, which had ruled the Byzantine Empire from 1259 to its fall in 1453. Though most of the figures in the genealogy can be verified to have been real historical figures, the veracity of his imperial descent is uncertain.

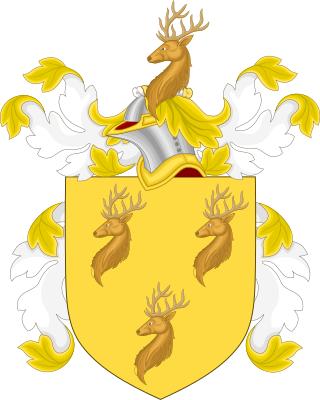

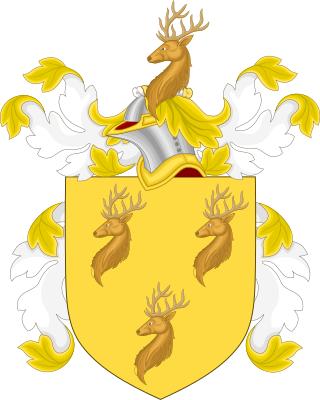

The Paleologus family, also called Palaiologos, Palaeologus and Paleologue, were a noble family from Pesaro in Italy who later established themselves in England in the 17th century. They might have been late-surviving descendants of the Palaiologos dynasty, rulers of the Byzantine Empire from 1259/1261 to its fall in 1453.

Theodore Paleologus, usually distinguished from his father of the same name by modern historians through being referred to as Theodore Junior or Theodore II, was the second son of the 16th/17th-century soldier and assassin Theodore Paleologus, and the oldest son to reach adulthood. Through his father, he was possibly a descendant of the Palaiologos dynasty of Byzantine emperors.

John Paleologus, full name John Theodore Paleologus, was the third son of the 16th/17th-century soldier and assassin Theodore Paleologus and, through his father, possibly a descendant of the Palaiologos dynasty of Byzantine emperors.

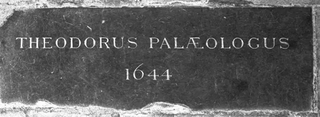

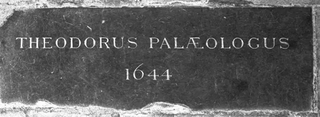

Theodore Paleologus, alternatively Theodorious or Theodorus and sometimes referred to as Theodore III by modern historians to distinguish him from his grandfather and his uncle, both by the same name, was the only known son of Ferdinand Paleologus. Through Ferdinand, Theodore, born in Barbados, might have been the last living male member of the Palaiologos dynasty, rulers of the Byzantine Empire from 1259 to its fall in 1453.

Godscall Paleologue or Paleologus was the last recorded living member of the Paleologus family, and through them possibly the last surviving member of the Palaiologos dynasty, rulers of the Byzantine Empire from 1259 to its fall in 1453. The posthumous daughter of privateer Theodore Paleologus, the only surviving source on Godscall is her baptismal records. Nothing is known of her life.

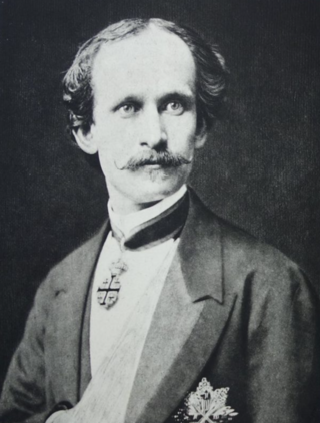

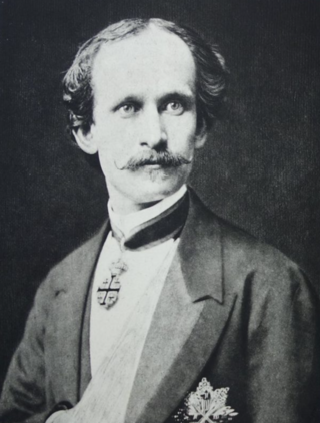

Demetrius Rhodocanakis was a London-based 19th-century Greek merchant, forger and pretender. Demetrius was the last great Byzantine pretender, claiming to be a prince directly descended from the Palaiologos dynasty of the Byzantine Empire from the 1860s onwards, and then the rightful Emperor of Constantinople, as Demetrios II Dukas Angelos Komnenos Palaiologos Rhodokanakis, from 1895 to his death. Though he lost support after 1895 due to his claims of Byzantine descent having been exposed as forgeries, Demetrius was at one point widely recognized as a Byzantine prince, achieving the recognition of not only the British Foreign Office, but also Pope Pius IX.

Peter Francis Mills, self-styled as Petros I Palaeologus, was an English eccentric and pretender from the Isle of Wight. Mills believed that his mother's last name, Colenutt, was derived from Koloneia, an ancient province of the Byzantine Empire, and consequently believed himself to be descended from the Palaiologos dynasty, the empire's final ruling family. Though his genealogy was never completely finished, Mills took the titles "Despot and Autokrator of the Romans" and "Duke of Morea", though he never achieved any widespread recognition and never seriously attempted to enforce his claims. Mills was often seen around his hometown of Newport dressed either in a military uniform or long, flowing robes. Upon his death in 1988, Mills' second wife Patricia took up his claim as "Empress of the Romans", his children by his first wife having denounced his pretensions as a "utter sham".

Enrico Constantino de Vigo Aleramico Lascaris Paleologo, self styled as Prince Enrico III, was an Italian eccentric, pretender and con artist. Possibly of humble origins, the young Enrico worked as a hairdresser in Genoa and had repeated run-ins with the law, at times being convicted of theft, slander and fraud, as well as not paying child support. In order to elevate his status, Enrico fabricated a genealogy which linked him to the Byzantine emperors of the Palaiologos dynasty and further enhanced his claimed descent by also claiming descent from the kings of Serbia, the kings of Jerusalem, the kings of the Two Sicilies and the Roman emperor Nero. As the legitimate "Emperor of Constantinople", Enrico claimed to be the head of different chivalric orders and also claimed the right to grant titles of knighthood and nobility. Such rights were mainly used by Enrico as a money-making scheme. Throughout his life as "prince", he hosted numerous "charity balls", wherein he sold titles to gullible people, some of them celebrities, for considerable amounts of money. Because the balls were frequently hosted at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas and Palm Beach in Florida, Enrico earned the nickname "The Emperor of Palm Beach".

Theodore Palaeologo or Theodore Attardo di Cristoforo de Bouillion, self-styled as Theodore Attardo di Cristoforo de Bouillion, Prince Nicephorus Comnenus Palaeologus, was a Maltese pretender to the throne of Greece, active in the late 19th century.

Eugenie Wickham, self-styled as Princess Eugenie Nicephorus Comnenus Palaeologus, was a Maltese pretender to the throne of Greece and the Byzantine Empire, active in the early 20th century. For most of her life, at least from the early 1860s onwards, Paleologue lived in Great Britain, from the late 1860s onwards in London. She was noted for her great generosity, despite not being rich, as well as her repeated attempts at becoming a sovereign in Greece.