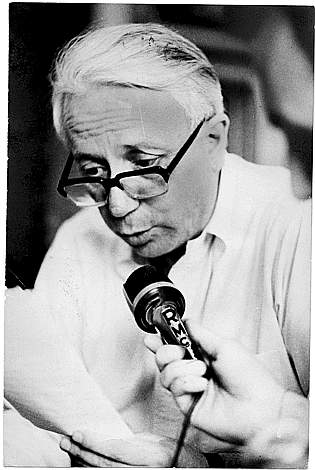

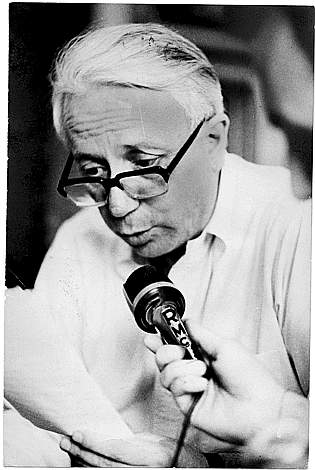

Enzo Biagi was an Italian journalist, writer and former partisan.

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war zone.

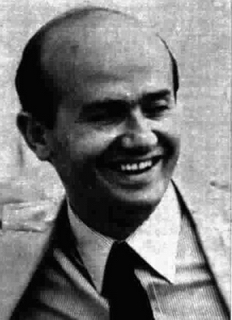

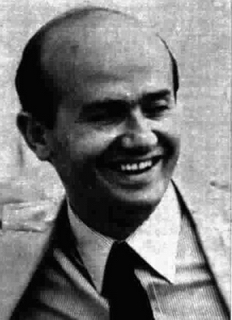

Indro Alessandro Raffaello Schizogene Montanelli was an Italian journalist, historian, and writer. He was one of the fifty World Press Freedom Heroes according to the International Press Institute. A volunteer for the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and an admirer of Benito Mussolini's dictatorship, Montanelli had a change of heart in 1943, and joined the liberal resistance group Giustizia e Libertà but was discovered and arrested along with his wife by Nazi authorities in 1944. Sentenced to death, he was able to flee to Switzerland the day before his scheduled execution by firing squad thanks to a secret service double agent.

Luigi Barzini Sr. in Orvieto, son of Ettore Barzini and Maria Bartoccini, was an Italian Senator and the most noted journalist and war correspondent of the second half of the Italian Belle Époque.

Giuseppe "Beppe" Severgnini is an Italian journalist, essayist and columnist.

The Journal des débats was a French newspaper, published between 1789 and 1944 that changed title several times. Created shortly after the first meeting of the Estates-General of 1789, it was, after the outbreak of the French Revolution, the exact record of the debates of the National Assembly, under the title Journal des Débats et des Décrets.

Ferdinando Russo was a prominent Neapolitan journalist primarily remembered as a dialect poet and composer of song lyrics.

Corrado Alvaro was an Italian journalist and writer of novels, short stories, screenplays and plays. He often used the verismo style to describe the hopeless poverty in his native Calabria. His first success was Gente in Aspromonte, which examined the exploitation of rural peasants by greedy landowners in Calabria, and is considered by many critics to be his masterpiece.

Agostino Trivulzio was an Italian Cardinal and papal legate. He was from a noble family in Milan, the eighth child of Giovanni Trivulzio di Borgomanero, a Councillor of the Dukes of Milan, and Angela Martinengo of Brescia, and was the nephew of Cardinal Gianantonio Trivulzio (1500–1508). Another uncle, Cardinal Antonio's brother Teodoro, was Governor of La Palice, of Genoa, of Milan, and a Marshal of France. Giovanni and Angela had a daughter named Damigella or Domtilla who was famous for her learning. Cardinal Agostino Trivulzio had a nephew named Giovanni, who married Laura Gonzaga.

The Premiolino is the oldest and one of the most important Italian journalism awards. It is made annually to six journalists from print media and television for their career achievements and their contributions to the freedom of the press.

Carlo Troya was a historian and politician who served as Prime Minister of the Two Sicilies from 3 April 1848 until 15 May 1848. Politically, he was a liberal Neo-Guelph who supported Italian unification. His primary historical interest was the study of the Early Middle Ages, to which he made lasting contributions.

The 1730 papal conclave elected Pope Clement XII as the successor to Pope Benedict XIII.

Teatro San Ferdinando is a theatre in Naples, Italy. It is named after King Ferdinand I of Naples. Located near Ponte Nuovo, it is to the southeast of the Teatro Totò in the western part of the neighborhood of Arenaccia. Built in the late eighteenth century, the seats are arranged in four box tiers, and the pit. It is most associated with Eduardo De Filippo and the productions of the 1950s under his direction. Closed in the 1980s and reopened in 2007, the San Fernando is managed by the Teatro Stabile of Naples.

The La Voce was an Italian daily newspaper published in Milan from March 1994 to April 1995. It was founded by journalist Indro Montanelli after a disagreement with Silvio Berlusconi, at that time owner of the Il Giornale newspaper of which Montanelli had been the founder and editor in chief after leaving Corriere della Sera. When Berlusconi announced his intention to run at the 1994 Italian general election in January 1994, he expected the paper to give his campaign full support. Although Montanelli's position was somehow aligned with Berlusconi's, he felt that the political career of Berlusconi could erode the editorial freedom and authority of the paper. Despite the initial success, the foundation of a new paper proved to be too much for Montanelli, who was 85 at the time. With sales going down drammatically following Berlusconi's victory, Montanelli was forced to close the paper after less than one year. He would later rejoin Corriere della Sera as a columnist.

Mario Cervi was an Italian essayist and journalist.

Storia d'Italia is a monumental work of the journalist and historian Indro Montanelli, written in collaboration with Roberto Gervaso and Mario Cervi from 1965 to 1997. The idea of a series of books about the history of Italy came to Montanelli after a conversation with Dino Buzzati. Montanelli initially proposed the idea to Mondadori, who wasn't interested. Montanelli then spoke to Longanesi, who agreed to publish the prologue, Storia di Roma in 1957. Following the success of the book, Rizzoli purchased the rights of the work and republished it in 1959. In 1965 Rizzoli, satisfied with the cultural impact of the book and its commercial success, agreed to publish the ambitious Storia d'Italia.

Leopoldo "Leo" Longanesi was an Italian journalist, publicist, screenplayer, playwright, writer, and publisher. Longanesi is mostly known in his country for his satirical works on Italian society and people. He also founded the eponymous publishing house in Milan in 1946 and was a mentor-like figure for Indro Montanelli.

Roberto Gervaso was an Italian writer and journalist. He won the Premio Bancarella twice: for L'Italia dei Comuni in 1967, and for Cagliostro in 1973.

Alessandro Gerbi, known as Sandro is an Italian journalist, author of several biographies and books on Italian contemporary history.

Count Gustavo Mazè de la Roche was an Italian general and politician. He was a senator of the Kingdom of Italy and Minister of War in the third Depretis government.