Gallery

- Peasant Woman with Red Shawl by Abram Arkhipov

- Pink Colour by Vladimir Baranov-Rossine

- Suprematism (1916) by Kazimir Malevich

The First Russian Art Exhibition (German : Erste Russische Kunstausstellung Berlin) was the first exhibition of Russian art held in Berlin following the Russian Revolution. It opened at the Gallery van Diemen, 21 Unter den Linden, on Sunday 15 October 1922. The exhibition was hosted by the Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, and proved controversial in relationship to the current developments in avant-garde art in Russia, most notably Constructivism.

In 1918 the Fine Arts section (IZO) of Narkompros established an International Bureau which included Nikolay Punin, David Shterenberg, Vladimir Tatlin and Vassily Kandinsky. [1] They worked with Ludwig Baehr, an artistically inclined ex-Officer in the German Imperial Army. Baehr had been on the German negotiating team for the Treaty of Brest Litovsk and was subsequently assigned to making links with the Russian intelligentsia. He established links with the Novembergruppe and the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Workers' Council for Art). In particular he carried messages between Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius and Max Pechstein. However he was also importing books and printing presses into Russia against the policy laid down by the German Foreign Office, and after his arrest in late 1919, this channel of communication no longer worked. In 1921 they gave Kandinsky a mandate to organise an exhibition of contemporary Russian art in Berlin. [2] However following political and aesthetic differences, the organisation of the exhibition was delayed as different personnel came to take on responsibility for the exhibition. In the end it was organised by Shterenberg, by then Director of IZO, Nathan Altman, and Naum Gabo.

The Catalogue was published by Workers International Relief to raise money in response to a drought and famine in the Volga area, particularly those lands occupied by the Volga Germans. It featured a foreword with sections written by David Shterenberg, Edwin Redslob (in his capacity as Reichskunstwart) and Arthur Holitscher, who in 1921 had published an account of his visit to Soviet Russia.

Shterenberg recounted how previous attempts by Russian artists to keep in touch with their western counterparts had been limited to the issuing of proclamations and manifestoes, but that with this exhibition a real step had been made to bring both groups together. The stated aim of the exhibition was to display the full story of the development of Russian art through both war and revolution. He referred to the transformative effect of the October Revolution in opening up art to mass of people, who had thus re-invigorated what had been the dead, official culture of "high art". This dynamic had also opened up new opportunities for Russia's creative forces, as their ideas could then be carried into the public spaces of towns and cities, which were being transformed by the revolution. There were new approaches being developed as regards urban decoration and architecture: the artist was no longer working in an isolated way, but rather in close contact with the people, who sometimes responded with enthusiasm and sometimes with scorn. Under these new testing circumstances some fell by the wayside, but others flourished. The limitation of the canvas, or the "stone coffins" which passed for housing were being swept away as the new society demanded a new environment. [3]

He continued that the immediately following the revolution the focus was on the decoration of public spaces, which however would be unsuitable for the exhibition. The exhibition thus focussed on the work of different movements active in Russia: the more traditional Union of Russian Artists, Mir Iskusstva, the Jack of Diamonds Group, the Impressionists and such leftist groups as the cubists, suprematists and the constructivists. Other exceptional work by artists who did not fit any of these groups was also included. Posters from the Russian Civil War had also been included, as had items from the State Porcelain factory. He also stated that the Soviet government sought German works of art to exhibit in Soviet Russia [3]

Redslob's contribution sought to balance the rooted-ness of artists in their own culture with a recognition of importance of contemporary issues in art. He described a shared responsibility for building Europe and said he was moved by the request for German art to be displayed in Russia.

Holitscher provided a statement where he suggested that artists were more able to communicate what was happening in a period of dissolution of one epoch and the emergence of another. Mentioning the art movements of the previous fifty years, he said that these should not be dismissed as "studio revolutions". He described how the coming of a spiritual revolution was first sensed by groups of precocious artists who would then be picked up by connoisseurs, collectors, dealers and museum directors, and even some snobs. Thus it becomes drawn into bourgeois society and the world of commercial cunning and social ambition. Only rarely does it become a matter of the pleasure and satisfaction of inner understanding. Nevertheless, it is the masses, whether fully or semiconsciously, who spur on the artist to new achievement. Thus the revolution which emerges from the artist's studio may not have as much impact as those who guide the political and economic interests of society, nevertheless there are periods when the enslavement of the masses has a greater role in the creative works of their contemporaries, even if the circumstances in which Praxiteles, Michelangelo or Dürer worked are no longer understood. In such times the artist has the power to shape the political and economic aspirations of the people. [4]

He continued that prior to a revolutionary transformation of society it was thought that the artist would be the first to embrace the new. However this is only partially true. The revolutionary artists is as much shaken as the rest of the general population, and only a few, singled out as human beings and as artists, follow their inner conviction and serve the destiny of the people. They attempt to link up with the masses while the "studio revolutionaries" stand on the sidelines, pretending to join in but in fact sabotaging the movement. While the new vision is becoming manifest in the public spaces of the streets, squares, bridges and barricades, becoming integrated into the vigorous life of the people, the "studio revolutionaries" crawl back to the haze of oil paint in their studios. The forward development of art is no longer dependent on the vision of a single prophetic man, but rather the natural urge of the people which rises up as a triumphant choir. The art theory born of the old individualised world is swept away by the victorious revolution. The art that arises in this way cannot be criticised in terms of artistic activity, but rather in terms of the political and economic circumstances which give rise to it. Such art will within itself create new aesthetic laws, will in itself mean revolution rather than simply a segment of revolution. "It will mean the totality of the creative forces of an epoch–not an isolated aspect of its many possible manifestations." [4]

Suprematism is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry, painted in a limited range of colors. The term suprematism refers to an abstract art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its end as late as 1960. The term covers many separate, but inextricably related, art movements that flourished at the time; including Suprematism, Constructivism, Russian Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Zaum, Imaginism, and Neo-primitivism. In Ukraine, many of the artists who were born, grew up or were active in what is now Belarus and Ukraine, are also classified in the Ukrainian avant-garde.

Cubo-Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm was an art movement, developed within Russian Futurism, that arose in early 20th century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo-Futurism was the main school of painting and sculpture practiced by the Russian Futurists. In 1913, the term "Cubo-Futurism" first came to describe works from members of the poetry group "Hylaeans", as they moved away from poetic Symbolism towards Futurism and zaum, the experimental "visual and sound poetry of Kruchenykh and Khlebninkov". Later in the same year the concept and style of "Cubo-Futurism" became synonymous with the works of artists within Ukrainian and Russian post-revolutionary avant-garde circles as they interrogated non-representational art through the fragmentation and displacement of traditional forms, lines, viewpoints, colours, and textures within their pieces. The impact of Cubo-Futurism was then felt within performance art societies, with Cubo-Futurist painters and poets collaborating on theatre, cinema, and ballet pieces that aimed to break theatre conventions through the use of nonsensical zaum poetry, emphasis on improvisation, and the encouragement of audience participation.

Constructivism is an early twentieth-century art movement founded in 1915 by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko. Abstract and austere, constructivist art aimed to reflect modern industrial society and urban space. The movement rejected decorative stylization in favour of the industrial assemblage of materials. Constructivists were in favour of art for propaganda and social purposes, and were associated with Soviet socialism, the Bolsheviks and the Russian avant-garde.

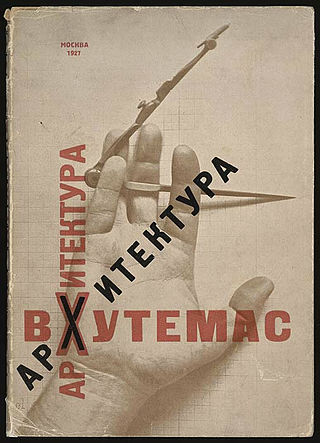

Vkhutemas was the Russian state art and technical school founded in 1920 in Moscow, replacing the Moscow Svomas.

Vladimir Davidovich Baranov-Rossiné, also spelled Baranoff-Rossiné, born Shulim Wolf Leib Baranov, was a painter and sculptor active in Russia and France. His work belonged to the avant-garde movement of Cubo-Futurism. He was also an inventor.

Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova was a Russian avant-garde artist, painter and teacher.

Nathan Isaevich Altman Russian: Натан Исаевич Альтман, romanized: Natan Isayevich Altman; Ukrainian: Натан Ісайович Альтман; December 22 [O.S. December 10] 1889 – December 12, 1970) was a Russian avant-garde artist, Cubist painter, stage designer and book illustrator, who was born in Ukraine in the Russian Empire and worked in France and the Soviet Union.

Expressionist architecture was an architectural movement in Europe during the first decades of the 20th century in parallel with the expressionist visual and performing arts that especially developed and dominated in Germany. Brick Expressionism is a special variant of this movement in western and northern Germany, as well as in the Netherlands.

Constructivist architecture was a constructivist style of modern architecture that flourished in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and early 1930s. Abstract and austere, the movement aimed to reflect modern industrial society and urban space, while rejecting decorative stylization in favor of the industrial assemblage of materials. Designs combined advanced technology and engineering with an avowedly communist social purpose. Although it was divided into several competing factions, the movement produced many pioneering projects and finished buildings, before falling out of favor around 1932. It has left marked effects on later developments in architecture.

David Petrovich Shterenberg was a Ukrainian-born Russian Soviet painter and graphic artist.

Paul Westheim was a German art historian and publisher of the magazine Das Kunstblatt. The fate of Westheim's art collection, which was sold after his death by Charlotte Weidler, has been the subject of major art restitution lawsuits.

Konstantin Aleksandrovich Vialov (1900–1976) was a 20th-century Russian artist.

The Institute of Artistic Culture was a theoretical and research based Russian artistic organisation founded in March Moscow in 1920 and continuing until 1924.

Karl Johansson was a Latvian-Soviet avant-garde artist.

Egység was a communist Hungarian art magazine published in Vienna and Berlin between 1922 and 1924. The full title was Egység, Irodalom, Müvészet which means "Unity, Literature, Art".

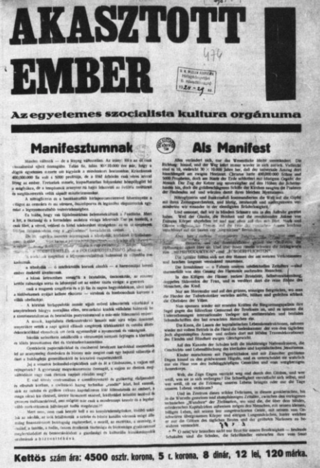

Akasztott Ember was a Hungarian language avant-garde art magazine published in Vienna by Sándor Barta. Five issues appeared between November 1922 and February 1923. It was subtitled "The Organ of Universal Socialist Culture".

IZO-Narkompros was the Department of Fine Arts of the People's Commissariat for Education established after the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia 1917. It was established in Petrograd on 29 January 1918.

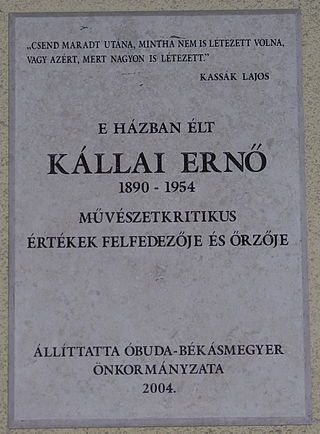

Ernő Kállai was a Hungarian art critic who was involved in the promotion of and theorisation around Constructivism.

Ludwig Baehr was an officer in the German Imperial Army who became both a diplomat and an artist. He played an important role in the cultural exchange between Russian and German artists following the Russian and German Revolutions.