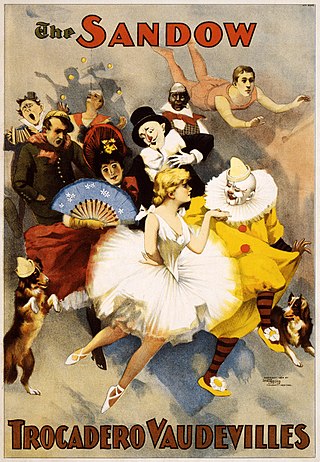

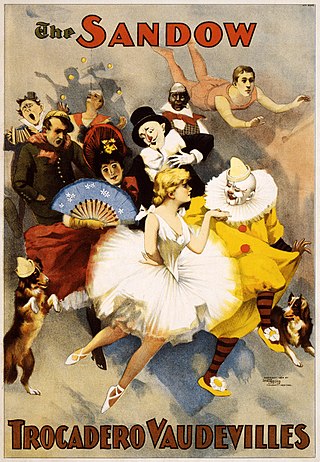

Vaudeville is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition or light poetry, interspersed with songs or ballets. It became popular in the United States and Canada from the early 1880s until the early 1930s, while changing over time.

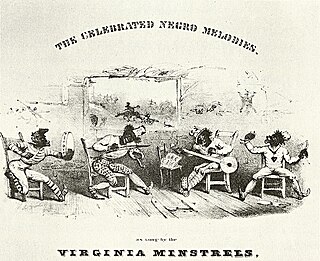

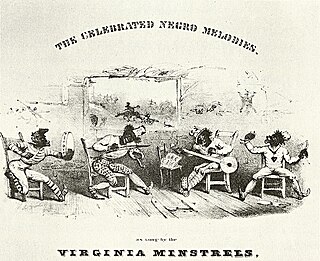

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of comically portraying racial stereotypes of African Americans. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows stereotyped blacks as dimwitted, lazy, buffoonish, cowardly, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent.

Trixie Smith, was an American blues singer and film actress. She made four dozen recordings and appeared in five films.

Ida M. Cox was an American singer and vaudeville performer, best known for her blues performances and recordings. She was billed as "The Uncrowned Queen of the Blues".

Julian Eltinge, born William Julian Dalton, was an American stage and film actor and female impersonator. After appearing in the Boston Cadets Revue at the age of ten in feminine garb, Eltinge garnered notice from other producers and made his first appearance on Broadway in 1904. As his star began to rise, he appeared in vaudeville and toured Europe and the United States, even giving a command performance before King Edward VII. Eltinge appeared in a series of musical comedies written specifically for his talents starting in 1910 with The Fascinating Widow, returning to vaudeville in 1918. His popularity soon earned him the moniker "Mr. Lillian Russell" for the popular beauty and musical comedy star.

Florence Mills, billed as the "Queen of Happiness", was an American cabaret singer, dancer, and comedian.

Theatre Owners Booking Association, or T.O.B.A., was the vaudeville circuit for African American performers in the 1920s. The theaters mostly had white owners, though about a third of them had Black owners, including the recently restored Morton Theater in Athens, Georgia, originally operated by "Pinky" Monroe Morton, and Douglass Theatre in Macon, Georgia owned and operated by Charles Henry Douglass. Theater owners booked jazz and blues musicians and singers, comedians, and other performers, including the classically trained, such as operatic soprano Sissieretta Jones, known as "The Black Patti", for black audiences.

Valaida Snow was an American jazz musician and entertainer who performed internationally. She was also known as "Little Louis" and "Queen of the Trumpet," a nickname given to her by W. C. Handy.

Black Vaudeville is a term that specifically describes Vaudeville-era African American entertainers and the milieus of dance, music, and theatrical performances they created. Spanning the years between the 1880s and early 1930s, these acts not only brought elements and influences unique to American black culture directly to African Americans but ultimately spread them beyond to both white American society and Europe.

Tom McIntosh was an African-American comedian who starred in many minstrel shows in the US from the 1870s to the 1900s. He was considered one of the funniest performers in this genre.

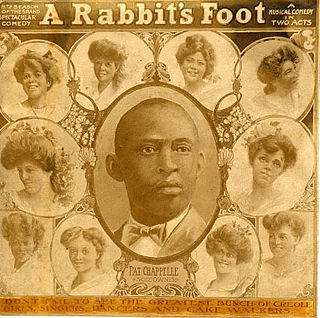

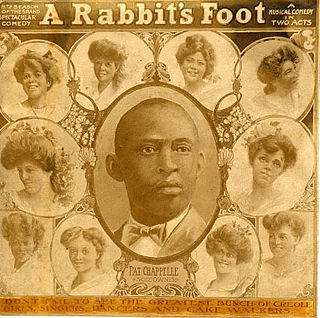

Sam T. Jack, a burlesque impresario, was a pioneer of the African-American vaudeville industry in the US with his Creole Burlesque Show. He was also known for staging increasingly risqué shows in Chicago, where young women appeared wearing only skin-colored tights.

John William Isham was an American vaudeville impresario who was known for his Octoroons and Oriental America shows. These had their roots in traditional minstrel shows but included chorus girls, sketches and operas. They were part of the transition to the American burlesque shows of the early 20th century.

The Columbia Theatre was an American burlesque theater on Seventh Avenue at the north end of Times Square in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Operated by the Columbia Amusement Company between 1910 and 1927, it specialized in "clean", family-oriented burlesque, similar to vaudeville. Many stars of the legitimate theater or of films were discovered at the Columbia. With loss of audiences to cinema and stock burlesque, the owners began to offer slightly more risqué material from 1925. The theater was closed in 1927, renovated and reopened in 1930 as a cinema called the Mayfair Theatre. It went through various subsequent changes and was later renamed the DeMille Theatre. Nothing is left of the theater.

Lillyn Brown, sometimes credited as Lillyan Brown, was an American singer, vaudeville entertainer and teacher who claimed to have been "the first professional vocalist to sing the blues in front of the public", in 1908. She was billed as "The Kate Smith of Harlem" and "The Original Gay 90's Gal".

The Whitman Sisters were four African-American sisters who were stars of Black Vaudeville. They ran their own performing touring company for over forty years from 1900 to 1943, becoming the longest-running and best-paid act on the T.O.B.A. circuit. They comprised Mabel (May) (b. Ohio; 1880–1942), Essie (Essie Barbara Whitman; b. Osceola, Arkansas, July 4, 1882 – May 7, 1963), Alberta "Bert" (b. Kansas; 1887–1964) and Alice (b. Georgia; 1900–December 29, 1968).

Lottie Gee(néeCharlotte O. Gee; 17 August 1886 Millboro, Virginia – 13 January 1973 Los Angeles) was an American entertainer who performed in shows and musicals during the Harlem Renaissance. She is perhaps best known as a performer in the 1921 Broadway hit, Shuffle Along, the show that launched the careers of Josephine Baker and Florence Mills.

Charles Anderson was an American vaudeville entertainer, singer and female impersonator, known as a pioneer performer of blues songs.

Gonzell White, also written Gonzelle White, was an American jazz, blues, and vaudeville performer in the United States.

Belle Davis was an American choreographer, dancer and singer who became famous in the UK before World War I. She was in a group called the "Octoroons" in America and moved to Britain in 1902 where she toured accompanied by young African American boys. She has been said to be the first black woman to make a recording.

The Griffin Sisters, Emma (1874–1918) and Mabel (1877–1918) Griffin, were American vaudeville performers in the late 1800s and early 1900s who became entrepreneurs and social activists and opened one of the first booking agencies owned by Black women. They publicly spoke out by demanding higher wages and better working conditions for Black performers at a time when discrimination and racism were both common in the entertainment industry.