Termites are a group of detritophagous eusocial insects which consume a variety of decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, leaf litter, and soil humus. They are distinguished by their moniliform antennae and the soft-bodied and often unpigmented worker caste for which they have been commonly termed "white ants"; however, they are not ants, to which they are only distantly related. About 2,972 extant species are currently described, 2,105 of which are members of the family Termitidae.

Terpenes are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers. In plants, terpenes and terpenoids are important mediators of ecological interactions, while some insects use some terpenes as a form of defense. Other functions of terpenoids include cell growth modulation and plant elongation, light harvesting and photoprotection, and membrane permeability and fluidity control.

The osmeterium is a defensive organ found in all papilionid larvae, in all stages. The organ is situated in the prothoracic segment and can be everted when the larva feels threatened. The everted organ resembles a fleshy forked tongue, and this along with the large eye-like spots on the body might be used to startle birds and small reptiles. The osmeterial organ remains inside the body in the thoracic region in an inverted position and is everted when the larva is disturbed in any way emitting a foul, disagreeable odor which serves to repel ants, small spiders and mantids. To humans, this odour is rather strong but not unpleasant, usually smelling like a concentrated scent of the caterpillar's food plant and pineapple.

Autothysis or suicidal altruism is the process where an animal destroys itself via an internal rupturing or explosion of an organ which ruptures the skin. The term was proposed by Ulrich Maschwitz and Eleonore Maschwitz in 1974 to describe the defensive mechanism of Colobopsis saundersi, a species of ant. It is caused by a contraction of muscles around a large gland that leads to the breaking of the gland wall. Some termites release a sticky secretion by rupturing a gland near the skin of their neck, producing a tar effect in defense against ants.

An allomone is a type of semiochemical produced and released by an individual of one species that affects the behaviour of a member of another species to the benefit of the originator but not the receiver. Production of allomones is a common form of defense against predators, particularly by plant species against insect herbivores. In addition to defense, allomones are also used by organisms to obtain their prey or to hinder any surrounding competitors.

Colobopsis saundersi, also called the Malaysian exploding ant, is a species of ant found in Malaysia and Brunei, belonging to the genus Colobopsis. A worker can explode suicidally and aggressively as an ultimate act of defense, an ability it has in common with several other species in this genus and a few other insects. The ant has an enormously enlarged mandibular gland, many times the size of other ants, which produces adhesive secretions for defense. According to a 2018 study, this species forms a species complex and is probably related to C. explodens, which is part of the C. cylindrica group.

Vachellia drepanolobium, more commonly known as Acacia drepanolobium or whistling thorn, is a swollen-thorn acacia native to East Africa. The whistling thorn grows up to 6 meters tall. It produces a pair of straight spines at each node, some of which have large bulbous bases. These swollen spines are naturally hollow and occupied by any one of several symbiotic ant species. The common name of the plant is derived from the observation that when wind blows over bulbous spines in which ants have made entry and exit holes, they produce a whistling noise.

Nitropentadecene, or more precisely (E)-1-nitropentadec-1-ene, is a highly toxic unsaturated nitroalkene, the only aliphatic nitro compound known to be synthesized by insects. It is produced by termite soldiers of genus Prorhinotermes (Isoptera, Rhinotermitidae) as a defensive chemical. Nitropentadecene is biosynthesized and stored in one of the exocrine glands, a frontal gland, of termite soldiers, and it is released upon attack of enemy.

Therea petiveriana, variously called the desert cockroach, seven-spotted cockroach, domino cockroach, or Indian domino cockroach, is a species of crepuscular cockroach found in southern India. They are members of a basal group within the cockroaches. This somewhat roundish and contrastingly marked cockroach is mainly found on the ground in scrub forest habitats where they may burrow under leaf litter or loose soil during the heat of the day.

Although projectiles are commonly used in human conflict, projectile use by organisms other than humans is relatively rare. However, some organisms are capable of using various different types of projectiles for defense or predation.

Chemical defense is a strategy employed by many organisms to avoid consumption by producing toxic or repellent metabolites or chemical warnings which incite defensive behavioral changes. The production of defensive chemicals occurs in plants, fungi, and bacteria, as well as invertebrate and vertebrate animals. The class of chemicals produced by organisms that are considered defensive may be considered in a strict sense to only apply to those aiding an organism in escaping herbivory or predation. However, the distinction between types of chemical interaction is subjective and defensive chemicals may also be considered to protect against reduced fitness by pests, parasites, and competitors. Repellent rather than toxic metabolites are allomones, a sub category signaling metabolites known as semiochemicals. Many chemicals used for defensive purposes are secondary metabolites derived from primary metabolites which serve a physiological purpose in the organism. Secondary metabolites produced by plants are consumed and sequestered by a variety of arthropods and, in turn, toxins found in some amphibians, snakes, and even birds can be traced back to arthropod prey. There are a variety of special cases for considering mammalian antipredatory adaptations as chemical defenses as well.

Insects have a wide variety of predators, including birds, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, carnivorous plants, and other arthropods. The great majority (80–99.99%) of individuals born do not survive to reproductive age, with perhaps 50% of this mortality rate attributed to predation. In order to deal with this ongoing escapist battle, insects have evolved a wide range of defense mechanisms. The only restraint on these adaptations is that their cost, in terms of time and energy, does not exceed the benefit that they provide to the organism. The further that a feature tips the balance towards beneficial, the more likely that selection will act upon the trait, passing it down to further generations. The opposite also holds true; defenses that are too costly will have a little chance of being passed down. Examples of defenses that have withstood the test of time include hiding, escape by flight or running, and firmly holding ground to fight as well as producing chemicals and social structures that help prevent predation.

Trail pheromones are semiochemicals secreted from the body of an individual to affect the behavior of another individual receiving it. Trail pheromones often serve as a multi purpose chemical secretion that leads members of its own species towards a food source, while representing a territorial mark in the form of an allomone to organisms outside of their species. Specifically, trail pheromones are often incorporated with secretions of more than one exocrine gland to produce a higher degree of specificity. Considered one of the primary chemical signaling methods in which many social insects depend on, trail pheromone deposition can be considered one of the main facets to explain the success of social insect communication today. Many species of ants, including those in the genus Crematogaster use trail pheromones.

Nasutitermes triodiae, also known as the cathedral termite, is a grass-eating species of Nasutitermitinae termite that can be found in Northern Territory, Australia. It is also sometimes referred to as the spinifex termite, since it is found in the spinifex grasslands. Very little research has been done on the underground nature of this species.

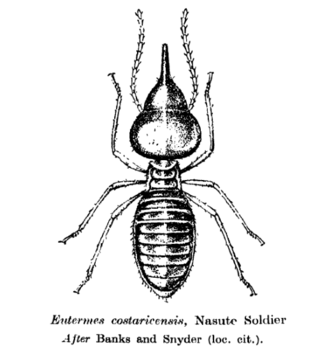

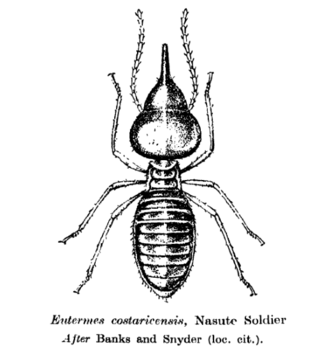

The Nasutitermitinae is a cosmopolitan subfamily of higher termites that includes more than 80 genera. They are most recognisable by the more highly derived soldier caste which exhibits vestigial mandibles and a protruding fontanellar process on the head from which they can "shoot" chemical weaponry. True workers of certain genera within this subfamily also exhibit a visible epicranial y suture, most notably found within the members of Nasutitermes. Notable genera include the notorious wood-eating Nasutitermes, and the conspicuous Hospitalitermes and Constrictotermes, both genera characterized by their behavior of forming large open-air foraging trails.

Constrictotermes is a genus of Neotropical higher termites within the subfamily Nasutitermitinae. They form large open-air foraging columns from which they travel to and from their sources of food, similar to the Indomalayan species of processionary termites. Species of this genus commonly build epigeal or arboreal nests and feed on a variety of lichens, rotted woods and mosses.

The Syntermitinae, also known as the mandibulate nasutes, is a Neotropical subfamily of higher termites represented by 21 genera and 103 species. The soldier caste of members of this subfamily have a conspicuous horn-like projection on the head which is adapted for chemical defense, similar to the fontanellar gun of true nasute termites (Nasutitermitinae). However unlike true nasutes, the mandibles of the soldiers are functional and highly developed, and they are unable to expel their chemical weaponry at a distance – instead relying on direct physical contact. Some genera, such as Syntermes or Labiotermes, have a highly reduced nasus and in some species it may appear absent altogether. Although the Syntermitinae were once grouped and considered basal within the Nasutitermitinae, they are not closely related with modern cladistic analyses showing Syntermitinae to be a separate and distinct lineage that is more closely related to either the Amitermes-group or MicrocerotermesTermitinae. It is believed the nasus evolved independently in Syntermitinae in an example of convergent evolution. Genera range from southern Mexico (Cahuallitermes) to Northern Argentina with the highest diversity occurring in the Brazilian Cerrado.

Rhynchotermes is a genus of Neotropical higher termites within the subfamily Syntermitinae, represented by 8 known species. Species of this genus are known for their soldiers which have highly developed sickle-shaped mandibles and a pronounced frontal tube superficially analogous to the fontanellar guns of true nasute termites. Most species forage above the surface in the open where they primarily feed on forest leaf litter. Nests are subterranean or are shallow and epigeic.

Insect pheromones are neurotransmitters that serve the chemical communication between individuals of an insect species. They thus differ from kairomones, in other words, neurotransmitters that transmit information to non-species organisms. Insects produce pheromones in special glands and release them into the environment. In the pheromone receptors of the sensory cells of the recipient, they produce a nerve stimulus even in very low concentrations, which ultimately leads to a behavioral response. Intraspecific communication of insects via these substances takes place in a variety of ways and serves, among other things, to find sexual partner, to maintain harmony in a colony of socially living insects, to mark territories or to find nest sites and food sources.