Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,000 species have been classified. They are easily identified by their geniculate (elbowed) antennae and the distinctive node-like structure that forms their slender waists.

Stephen Jay Gould was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In 1996, Gould was hired as the Vincent Astor Visiting Research Professor of Biology at New York University, after which he divided his time teaching between there and Harvard.

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of human societies, sociobiology is closely allied to evolutionary anthropology, human behavioral ecology, evolutionary psychology, and sociology.

The Selfish Gene is a 1976 book on evolution by ethologist Richard Dawkins that promotes the gene-centred view of evolution, as opposed to views focused on the organism and the group. The book builds upon the thesis of George C. Williams's Adaptation and Natural Selection (1966); it also popularized ideas developed during the 1960s by W. D. Hamilton and others. From the gene-centred view, it follows that the more two individuals are genetically related, the more sense it makes for them to behave cooperatively with each other.

Berthold Karl HölldoblerBVO is a German zoologist, sociobiologist and evolutionary biologist who studies evolution and social organization in ants. He is the author of several books, including The Ants, for which he and his co-author, E. O. Wilson, received the Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction writing in 1991.

William Donald Hamilton was a British evolutionary biologist, recognised as one of the most significant evolutionary theorists of the 20th century. Hamilton became known for his theoretical work expounding a rigorous genetic basis for the existence of altruism, an insight that was a key part of the development of the gene-centered view of evolution. He is considered one of the forerunners of sociobiology. Hamilton published important work on sex ratios and the evolution of sex. From 1984 to his death in 2000, he was a Royal Society Research Professor at Oxford University.

Myrmecology is a branch of entomology focusing on the study of ants. Ants continue to be a model of choice for the study of questions on the evolution of social systems because of their complex and varied forms of social organization. Their diversity and prominence in ecosystems also has made them important components in the study of biodiversity and conservation. In the 2000s, ant colonies began to be studied and modeled for their relevance in machine learning, complex interactive networks, stochasticity of encounter and interaction networks, parallel computing, and other computing fields.

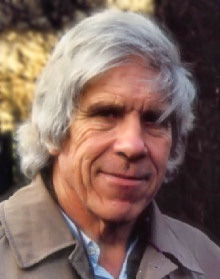

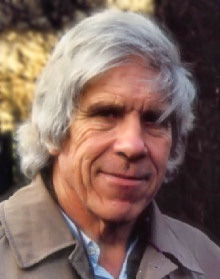

Richard Charles Lewontin was an American evolutionary biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and social commentator. A leader in developing the mathematical basis of population genetics and evolutionary theory, he applied techniques from molecular biology, such as gel electrophoresis, to questions of genetic variation and evolution.

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

The Texas leafcutter ant is a species of fungus-farming ant in the subfamily Myrmicinae. It is found in Texas, Louisiana, and north-eastern Mexico. Other common names include town ant, parasol ant, fungus ant, cut ant, and night ant. It harvests leaves from over 200 plant species, and is considered a major pest of agricultural and ornamental plants, as it can defoliate a citrus tree in less than 24 hours. Every colony has several queens and up to 2 million workers. Nests are built in well-drained, sandy or loamy soil, and may reach a depth of 6 m (20 ft), have 1000 entrance holes, and occupy 420 m2 (4,500 sq ft).

Journey to the Ants: a Story of Scientific Exploration is a 1994 book by the evolutionary biologist Bert Hölldobler and the biologist Edward O. Wilson. The book was written as a popularized account for the layman of the science earlier presented in their book The Ants (1990), which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1991.

Sociobiology: The New Synthesis is a book by the biologist E. O. Wilson. It helped start the sociobiology debate, one of the great scientific controversies in biology of the 20th century and part of the wider debate about evolutionary psychology and the modern synthesis of evolutionary biology. Wilson popularized the term "sociobiology" as an attempt to explain the evolutionary mechanics behind social behaviour such as altruism, aggression, and the nurturing of the young. It formed a position within the long-running nature versus nurture debate. The fundamental principle guiding sociobiology is that an organism's evolutionary success is measured by the extent to which its genes are represented in the next generation.

Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature is a 1984 book by the evolutionary geneticist Richard Lewontin, the neurobiologist Steven Rose, and the psychologist Leon Kamin, in which the authors criticize sociobiology and genetic determinism and advocate a socialist society. Its themes include the relationship between biology and society, the nature versus nurture debate, and the intersection of science and ideology.

Robert Ludlow "Bob" Trivers is an American evolutionary biologist and sociobiologist. Trivers proposed the theories of reciprocal altruism (1971), parental investment (1972), facultative sex ratio determination (1973), and parent–offspring conflict (1974). He has also contributed by explaining self-deception as an adaptive evolutionary strategy and discussing intragenomic conflict.

Thomas Eisner was a German-American entomologist and ecologist, known as the "father of chemical ecology." He was a Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Chemical Ecology at Cornell University, and director of the Cornell Institute for Research in Chemical Ecology (CIRCE). He was a world authority on animal behavior, ecology, and evolution, and, together with his Cornell colleague Jerrold Meinwald, was one of the pioneers of chemical ecology, the discipline dealing with the chemical interactions of organisms. He was author or co-author of some 400 scientific articles and seven books.

On Human Nature is a book by the biologist E. O. Wilson, in which the author attempts to explain human nature and society through sociobiology. Wilson argues that evolution has left its traces on characteristics such as generosity, self-sacrifice, worship and the use of sex for pleasure, and proposes a sociobiological explanation of homosexuality.

Walter R. Tschinkel is an American myrmecologist, entomologist and Distinguished Research Professor of Biological Science and R.O. Lawton Distinguished Professor emeritus at Florida State University. He is the author of the Pulitzer Prize nominated book The Fire Ants, the book Ant Architecture: The Wonder, Beauty, and Science of Underground Nests, and more than 150 original research papers on the natural history, ecology, nest architecture and organization of ant societies; chemical communication in beetles; and the mysterious fairy circles of the Namib desert. His casts of ant nests and botanical drawings appear in numerous museums of art and natural history, from Hong Kong to Paris.

The Sociobiology Study Group was an academic organization formed to specifically counter sociobiological explanations of human behavior, particularly those expounded by the Harvard entomologist E. O. Wilson in Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975). The group formed in Boston, Massachusetts and consisted of both professors and students, predominantly left-wing and Marxist.

Mark Moffett is an American tropical biologist who studies the ecology of tropical forest canopies and the social behavior of animals and humans. He is also the author of several popular science books and is noted for his macrophotography documenting ant biology.

The history of evolutionary psychology began with Charles Darwin, who said that humans have social instincts that evolved by natural selection. Darwin's work inspired later psychologists such as William James and Sigmund Freud but for most of the 20th century psychologists focused more on behaviorism and proximate explanations for human behavior. E. O. Wilson's landmark 1975 book, Sociobiology, synthesized recent theoretical advances in evolutionary theory to explain social behavior in animals, including humans. Jerome Barkow, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby popularized the term "evolutionary psychology" in their 1992 book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and The Generation of Culture. Like sociobiology before it, evolutionary psychology has been embroiled in controversy, but evolutionary psychologists see their field as gaining increased acceptance overall.