Q fever or query fever is a disease caused by infection with Coxiella burnetii, a bacterium that affects humans and other animals. This organism is uncommon, but may be found in cattle, sheep, goats, and other domestic mammals, including cats and dogs. The infection results from inhalation of a spore-like small-cell variant, and from contact with the milk, urine, feces, vaginal mucus, or semen of infected animals. Rarely, the disease is tick-borne. The incubation period can range from 9 to 40 days. Humans are vulnerable to Q fever, and infection can result from even a few organisms. The bacterium is an obligate intracellular pathogenic parasite.

Rickettsia is a genus of nonmotile, gram-negative, nonspore-forming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that may occur in the forms of cocci, bacilli, or threads. The genus was named after Howard Taylor Ricketts in honor of his pioneering work on tick-borne spotted fever.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial disease spread by ticks. It typically begins with a fever and headache, which is followed a few days later with the development of a rash. The rash is generally made up of small spots of bleeding and starts on the wrists and ankles. Other symptoms may include muscle pains and vomiting. Long-term complications following recovery may include hearing loss or loss of part of an arm or leg.

Rickettsia rickettsii is a Gram-negative, intracellular, cocco-bacillus bacterium that was first discovered in 1902. Having a reduced genome, the bacterium harvests nutrients from its host cell to carry out respiration, making it an organo-heterotroph. Maintenance of its genome is carried out through vertical gene transfer where specialization of the bacterium allows it to shuttle host sugars directly into its TCA cycle.

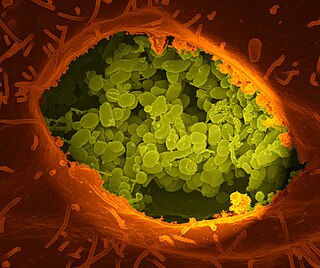

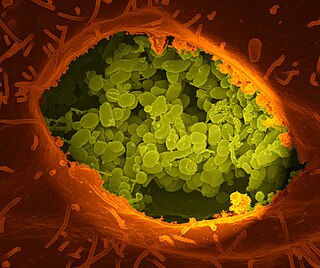

Coxiella burnetii is an obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen, and is the causative agent of Q fever. The genus Coxiella is morphologically similar to Rickettsia, but with a variety of genetic and physiological differences. C. burnetii is a small Gram-negative, coccobacillary bacterium that is highly resistant to environmental stresses such as high temperature, osmotic pressure, and ultraviolet light. These characteristics are attributed to a small cell variant form of the organism that is part of a biphasic developmental cycle, including a more metabolically and replicatively active large cell variant form. It can survive standard disinfectants, and is resistant to many other environmental changes like those presented in the phagolysosome.

Herald Rea Cox (1907–1986) was an American bacteriologist. The bacterial family Coxiellaceae and the genus Coxiella, which include the organism that causes Q fever, are named after him.

Rickettsialpox is a mite-borne infectious illness caused by bacteria of the genus Rickettsia. Physician Robert Huebner and self-trained entomologist Charles Pomerantz played major roles in identifying the cause of the disease after an outbreak in 1946 in a New York City apartment complex, documented in "The Alerting of Mr. Pomerantz," an article by medical writer Berton Roueché.

Sir Michael George Parke Stoker was a British physician and medical researcher in virology.

Orientia tsutsugamushi is a mite-borne bacterium belonging to the family Rickettsiaceae and is responsible for a disease called scrub typhus in humans. It is a natural and an obligate intracellular parasite of mites belonging to the family Trombiculidae. With a genome of only 2.0–2.7 Mb, it has the most repeated DNA sequences among bacterial genomes sequenced so far. The disease, scrub typhus, occurs when infected mite larvae accidentally bite humans. This infection can prove fatal if prompt doxycycline therapy is not started.

Rickettsia akari is a species of Rickettsia which causes rickettsialpox.

Rickettsia typhi is a small, aerobic, obligate intracellular, rod shaped gram negative bacterium. It belongs to the typhus group of the Rickettsia genus, along with R. prowazekii. R. typhi has an uncertain history, as it may have long gone shadowed by epidemic typhus. This bacterium is recognized as a biocontainment level 2/3 organism. R. typhi is a flea-borne disease that is best known to be the causative agent for the disease murine typhus, which is an endemic typhus in humans that is distributed worldwide. As with all rickettsial organisms, R. typhi is a zoonotic agent that causes the disease murine typhus, displaying non-specific mild symptoms of fevers, headaches, pains and rashes. There are two cycles of R. typhi transmission from animal reservoirs containing R. typhi to humans: a classic rat-flea-rat cycle that is most well studied and common, and a secondary periodomestic cycle that could involve cats, dogs, opossums, sheep, and their fleas.

Charles Pomerantz was a pest control expert and self-trained entomologist who played a pivotal role in identifying the etiology of a 1946 outbreak in New York City of what was later named rickettsialpox. In subsequent years, he spoke before audiences at colleges and other public forums about the menace from pests.

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is a bacterial infection spread by the bite of a tick. Symptoms may include fever, headache, muscle pain, and a rash. At the site of the bite there is typically a red skin sore with a dark center. The onset of symptoms usually occurs 4–10 days after the bite. Complications are rare but may include joint inflammation. Some people do not develop symptoms.

Rickettsia felis is a species of bacterium, the pathogen that causes cat-flea typhus in humans, also known as flea-borne spotted fever. Rickettsia felis also is regarded as the causative organism of many cases of illnesses generally classed as fevers of unknown origin in humans in Africa.

Barrie Patrick Marmion was an English microbiologist who spent the majority of his career in Australia. He is known for his work on Q fever, and led the team that developed the first vaccine against the bacteria that causes it.

Winston Harvey Price was an American scientist and professor of epidemiology with a special interest in infectious diseases, who made media headlines in 1957, when he reported details of a vaccine for the common cold after isolating the first rhinovirus. He was acknowledged by the director of the Public Health Research Institute at the time. However, other specialists in the field of vaccine research have disputed his methods and data.

Wallace Prescott Rowe was an American virologist, known for his research on retroviruses and oncoviruses and as a co-discoverer of adenoviruses.

Paul Fiset was a Canadian-American microbiologist and virologist. His research helped to develop one of the first successful Q fever vaccines, noted by The New York Times. Fiset was born in Quebec, Canada, and attended Laval University, where he earned a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1949. He subsequently attended Cambridge University, where he received a PhD degree in 1956. As a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, he also researched other bacterial diseases such as typhus and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, in addition to Q fever.

Edwin Herman Lennette was an American physician, virologist, and pioneer of diagnostic virology.

Janet W. Hartley is an American virologist who worked at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). A Washingtonian, she received degrees in bacteriology and virology research before graduating with a Ph.D. and joining the National Institutes of Health lab of Bob Huebner. Later becoming section head for the virology department, she would spend the next four decades researching a variety of viruses, discovering numerous species, and identifying new methods for quantifying viruses and the involvement of viral infection in cancer development.