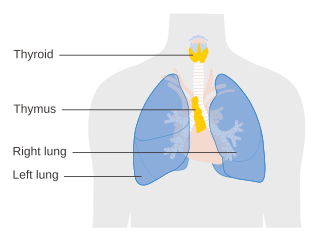

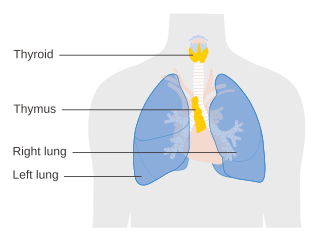

The thymus is a specialized primary lymphoid organ of the immune system. Within the thymus, thymus cell lymphocytes or T cells mature. T cells are critical to the adaptive immune system, where the body adapts to specific foreign invaders. The thymus is located in the upper front part of the chest, in the anterior superior mediastinum, behind the sternum, and in front of the heart. It is made up of two lobes, each consisting of a central medulla and an outer cortex, surrounded by a capsule.

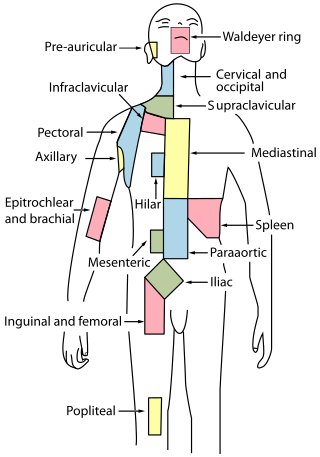

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphoid organs, lymphatic tissue and lymph. Lymph is a clear fluid carried by the lymphatic vessels back to the heart for re-circulation. The Latin word for lymph, lympha, refers to the deity of fresh water, "Lympha".

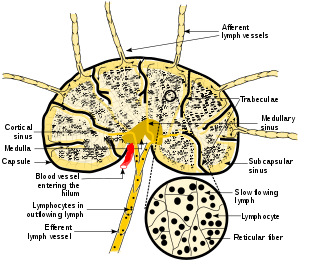

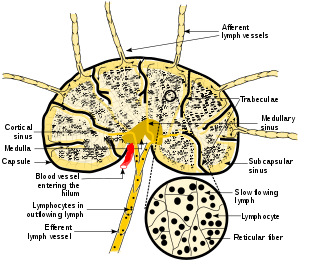

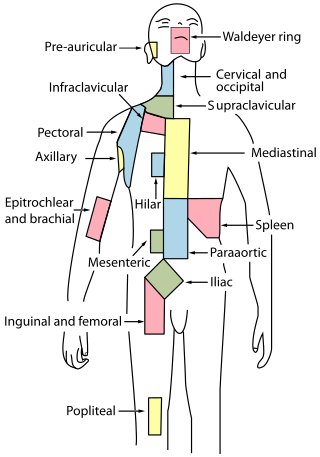

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that include B and T cells. Lymph nodes are important for the proper functioning of the immune system, acting as filters for foreign particles including cancer cells, but have no detoxification function.

Palatine tonsils, commonly called the tonsils and occasionally called the faucial tonsils, are tonsils located on the left and right sides at the back of the throat, which can often be seen as flesh-colored, pinkish lumps. Tonsils only present as "white lumps" if they are inflamed or infected with symptoms of exudates and severe swelling.

Tonsillectomy is a surgical procedure in which both palatine tonsils are fully removed from the back of the throat. The procedure is mainly performed for recurrent tonsillitis, throat infections and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). For those with frequent throat infections, surgery results in 0.6 fewer sore throats in the following year, but there is no evidence of long term benefits. In children with OSA, it results in improved quality of life.

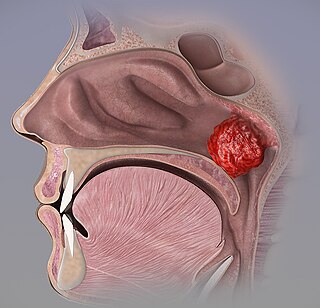

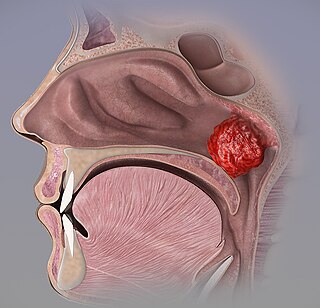

In anatomy, the pharyngeal tonsil, also known as the nasopharyngeal tonsil or adenoid, is the superior-most of the tonsils. It is a mass of lymphoid tissue located behind the nasal cavity, in the roof and the posterior wall of the nasopharynx, where the nose blends into the throat. In children, it normally forms a soft mound in the roof and back wall of the nasopharynx, just above and behind the uvula.

Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils in the upper part of the throat. It can be acute or chronic. Acute tonsillitis typically has a rapid onset. Symptoms may include sore throat, fever, enlargement of the tonsils, trouble swallowing, and enlarged lymph nodes around the neck. Complications include peritonsillar abscess (quinsy).

Tonsil stones, also known as tonsilloliths, are mineralizations of debris within the crevices of the tonsils. When not mineralized, the presence of debris is known as chronic caseous tonsillitis (CCT). Symptoms may include bad breath, foreign body sensation, sore throat, pain or discomfort with swallowing, and cough. Generally there is no pain, though there may be the feeling of something present. The presence of tonsil stones may be otherwise undetectable; however, some people have reported seeing white material in the rear of their throat.

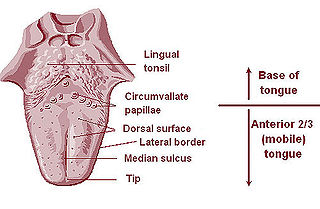

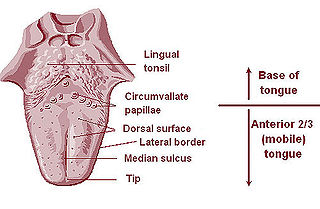

The lingual tonsils are a collection of lymphatic tissue located in the lamina propria of the root of the tongue. This lymphatic tissue consists of the lymphatic nodules rich in cells of the immune system (immunocytes). The immunocytes initiate the immune response when the lingual tonsils get in contact with invading microorganisms.

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is a component of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) which works in the immune system to protect the body from invasion in the gut.

Myeloid tissue, in the bone marrow sense of the word myeloid, is tissue of bone marrow, of bone marrow cell lineage, or resembling bone marrow, and myelogenous tissue is any tissue of, or arising from, bone marrow; in these senses the terms are usually used synonymously, as for example with chronic myeloid/myelogenous leukemia.

The mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), also called mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue, is a diffuse system of small concentrations of lymphoid tissue found in various submucosal membrane sites of the body, such as the gastrointestinal tract, nasopharynx, thyroid, breast, lung, salivary glands, eye, and skin. MALT is populated by lymphocytes such as T cells and B cells, as well as plasma cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, each of which is well situated to encounter antigens passing through the mucosal epithelium. In the case of intestinal MALT, M cells are also present, which sample antigen from the lumen and deliver it to the lymphoid tissue. MALT constitute about 50% of the lymphoid tissue in human body. Immune responses that occur at mucous membranes are studied by mucosal immunology.

Waldeyer's tonsillar ring is a ringed arrangement of lymphoid organs in the pharynx. Waldeyer's ring surrounds the naso- and oropharynx, with some of its tonsillar tissue located above and some below the soft palate.

Adenoid hypertrophy, also known as enlarged adenoids refers to an enlargement of the adenoid that is linked to nasopharyngeal mechanical blockage and/or chronic inflammation. Adenoid hypertrophy is a characterized by hearing loss, recurrent otitis media, mucopurulent rhinorrhea, chronic mouth breathing, nasal airway obstruction, increased infection susceptibility, and dental malposition.

Adenoiditis is the inflammation of the adenoid tissue usually caused by an infection. Adenoiditis is treated using medication or surgical intervention.

The pharynx is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea. It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its structure varies across species. The pharynx carries food to the esophagus and air to the larynx. The flap of cartilage called the epiglottis stops food from entering the larynx.

The human palatine tonsils (PT) are covered by stratified squamous epithelium that extends into deep and partly branched tonsillar crypts, of which there are about 10 to 30. The crypts greatly increase the contact surface between environmental influences and lymphoid tissue. In an average adult palatine tonsil the estimated epithelial surface area of the crypts is 295 cm2, in addition to the 45 cm2 of epithelium covering the oropharyngeal surface.

Lymph node stromal cells are essential to the structure and function of the lymph node whose functions include: creating an internal tissue scaffold for the support of hematopoietic cells; the release of small molecule chemical messengers that facilitate interactions between hematopoietic cells; the facilitation of the migration of hematopoietic cells; the presentation of antigens to immune cells at the initiation of the adaptive immune system; and the homeostasis of lymphocyte numbers. Stromal cells originate from multipotent mesenchymal stem cells.

The avian immune system is the system of biological structures and cellular processes that protects birds from disease.

Carcinoma of the tonsil is a type of squamous cell carcinoma. The tonsil is the most common site of squamous cell carcinoma in the oropharynx. It comprises 23.1% of all malignancies of the oropharynx. The tumors frequently present at advanced stages, and around 70% of patients present with metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes. . The most reported complaints include sore throat, otalgia or dysphagia. Some patients may complain of feeling the presence of a lump in the throat. Approximately 20% patients present with a node in the neck as the only symptom.