Louse is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a result of developments in phylogenetic research.

The Mallophaga are a possibly paraphyletic section of lice, known as chewing lice, biting lice, or bird lice, containing more than 3000 species. These lice are external parasites that feed mainly on birds, although some species also feed on mammals. They infest both domestic and wild mammals and birds, and cause considerable irritation to their hosts. They have paurometabolis or incomplete metamorphosis.

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- di- "two", and πτερόν pteron "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced mechanosensory organs known as halteres, which act as high-speed sensors of rotational movement and allow dipterans to perform advanced aerobatics. Diptera is a large order containing an estimated 1,000,000 species including horse-flies, crane flies, hoverflies, mosquitoes and others, although only about 125,000 species have been described.

Hemiptera is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from 1 mm (0.04 in) to around 15 cm (6 in), and share a common arrangement of piercing-sucking mouthparts. The name "true bugs" is often limited to the suborder Heteroptera.

Thrips are minute, slender insects with fringed wings and unique asymmetrical mouthparts. Entomologists have described approximately 7,700 species. They fly only weakly and their feathery wings are unsuitable for conventional flight; instead, thrips exploit an unusual mechanism, clap and fling, to create lift using an unsteady circulation pattern with transient vortices near the wings.

The Pentatomoidea are a superfamily of insects in the suborder Heteroptera of the order Hemiptera. As hemipterans, they possess a common arrangement of sucking mouthparts. The roughly 7000 species under Pentatomoidea are divided into 21 families. Among these are the stink bugs and shield bugs, jewel bugs, giant shield bugs, and burrower bugs.

The Haliplidae are a family of water beetles that swim using an alternating motion of the legs. They are therefore clumsy in water, and prefer to get around by crawling. The family consists of about 200 species in 5 genera, distributed wherever there is freshwater habitat; it is the only extant member of superfamily Haliploidea. They are also known as crawling water beetles or haliplids.

The Asilidae are the robber fly family, also called assassin flies. They are powerfully built, bristly flies with a short, stout proboscis enclosing the sharp, sucking hypopharynx. The name "robber flies" reflects their expert predatory habits; they feed mainly or exclusively on other insects and, as a rule, they wait in ambush and catch their prey in flight.

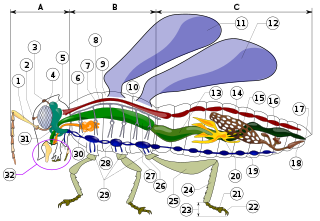

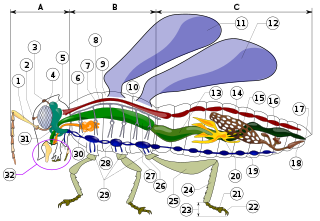

The mouthparts of arthropods have evolved into a number of forms, each adapted to a different style or mode of feeding. Most mouthparts represent modified, paired appendages, which in ancestral forms would have appeared more like legs than mouthparts. In general, arthropods have mouthparts for cutting, chewing, piercing, sucking, shredding, siphoning, and filtering. This article outlines the basic elements of four arthropod groups: insects, myriapods, crustaceans and chelicerates. Insects are used as the model, with the novel mouthparts of the other groups introduced in turn. Insects are not, however, the ancestral form of the other arthropods discussed here.

The mandible of an arthropod is a pair of mouthparts used either for biting or cutting and holding food. Mandibles are often simply called jaws. Mandibles are present in the extant subphyla Myriapoda, Crustacea and Hexapoda. These groups make up the clade Mandibulata, which is currently believed to be the sister group to the rest of arthropods, the clade Arachnomorpha.

In arthropods, the maxillae are paired structures present on the head as mouthparts in members of the clade Mandibulata, used for tasting and manipulating food. Embryologically, the maxillae are derived from the 4th and 5th segment of the head and the maxillary palps; segmented appendages extending from the base of the maxilla represent the former leg of those respective segments. In most cases, two pairs of maxillae are present and in different arthropod groups the two pairs of maxillae have been variously modified. In crustaceans, the first pair are called maxillulae.

Insects have mouthparts that may vary greatly across insect species, as they are adapted to particular modes of feeding. The earliest insects had chewing mouthparts. Most specialisation of mouthparts are for piercing and sucking, and this mode of feeding has evolved a number of times independently. For example, mosquitoes and aphids both pierce and suck, though female mosquitoes feed on animal blood whereas aphids feed on plant fluids.

Psocodea is a taxonomic group of insects comprising the bark lice, book lice and parasitic lice. It was formerly considered a superorder, but is now generally considered by entomologists as an order. Despite the greatly differing appearance of parasitic lice (Phthiraptera), they are believed to have evolved from within the former order Psocoptera, which contained the bark lice and book lice, now found to be paraphyletic. They are often regarded as the most primitive of the hemipteroids. Psocodea contains around 11,000 species, divided among four suborders and more than 70 families. They range in size from 1–10 millimetres (0.04–0.4 in) in length.

Insect morphology is the study and description of the physical form of insects. The terminology used to describe insects is similar to that used for other arthropods due to their shared evolutionary history. Three physical features separate insects from other arthropods: they have a body divided into three regions, three pairs of legs, and mouthparts located outside of the head capsule. This position of the mouthparts divides them from their closest relatives, the non-insect hexapods, which include Protura, Diplura, and Collembola.

Paraneoptera or Acercaria is a superorder of insects which includes lice, thrips, and hemipterans, the true bugs. It also includes the extinct order Permopsocida, known from fossils dating from the Early Permian to the mid-Cretaceous.

Dipteran morphology differs in some significant ways from the broader morphology of insects. The Diptera is a very large and diverse order of mostly small to medium-sized insects. They have prominent compound eyes on a mobile head, and one pair of functional, membraneous wings, which are attached to a complex mesothorax. The second pair of wings, on the metathorax, are reduced to halteres. The order's fundamental peculiarity is its remarkable specialization in terms of wing shape and the morpho-anatomical adaptation of the thorax – features which lend particular agility to its flying forms. The filiform, stylate or aristate antennae correlate with the Nematocera, Brachycera and Cyclorrhapha taxa respectively. It displays substantial morphological uniformity in lower taxa, especially at the level of genus or species. The configuration of integumental bristles is of fundamental importance in their taxonomy, as is wing venation. It displays a complete metamorphosis, or holometabolous development. The larvae are legless, and have head capsules with mandibulate mouthparts in the Nematocera. The larvae of "higher flies" (Brachycera) are however headless and wormlike, and display only three instars. Pupae are obtect in the Nematocera, or coarcate in Brachycera.

Insects are among the most diverse groups of animals on the planet, including more than a million described species and representing more than half of all known living organisms. The number of extant species is estimated at between six and ten million, found in nearly all environments, although only a small number of species occur in the oceans. This large extant means that the dietary habits of taxa include a large variety of behaviors.

Thrips tabaci is a species of very small insect in the genus Thrips in the order Thysanoptera. It is commonly known as the onion thrips, the potato thrips, the tobacco thrips or the cotton seedling thrips. It is an agricultural pest that can damage crops of onions and other plants, and it can additionally act as a vector for plant viruses.

Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis is a species of thrips in the family Thripidae. It is most commonly known as the greenhouse thrips, the glasshouse thrip or black tea thrips. This species of thrips was first described in 1833 by Bouché in Berlin, Germany. H. haemorrhoidalis also has many synonyms depending on where they were described from such as: H. adonidum Haliday, H. semiaureus Girault, H. abdominalis Reuter, H. angustior Priesner, H. ceylonicus Schultz, Dinurothrips rufiventris Girault. In New Zealand, H. haemorrhoidalis is one of the four species belonging to the subfamily Panchaetothripinae.