Naples is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's administrative limits as of 2022. Its province-level municipality is the third-most populous metropolitan city in Italy with a population of 3,115,320 residents, and its metropolitan area stretches beyond the boundaries of the city wall for approximately 30 kilometres.

An ossuary is a chest, box, building, well, or site made to serve as the final resting place of human skeletal remains. They are frequently used where burial space is scarce. A body is first buried in a temporary grave, then after some years the skeletal remains are removed and placed in an ossuary. The greatly reduced space taken up by an ossuary means that it is possible to store the remains of many more people in a single tomb than possible in coffins. The practice is sometimes known as grave recycling.

Piazza del Plebiscito is a large public square in central Naples, Italy.

The Duchy of Naples began as a Byzantine province that was constituted in the seventh century, in the reduced coastal lands that the Lombards had not conquered during their invasion of Italy in the sixth century. It was governed by a military commander (dux), and rapidly became a de facto independent state, lasting more than five centuries during the Early and High Middle Ages. Naples remains a significant metropolitan city in present-day Italy.

Castel Nuovo, often called Maschio Angioino, is a medieval castle located in front of Piazza Municipio and the city hall in central Naples, Campania, Italy. Its scenic location and imposing size makes the castle, first erected in 1279, one of the main architectural landmarks of the city. It was a royal seat for kings of Naples, Aragon and Spain until 1815.

Sant'Anna dei Lombardi,, and also known as Santa Maria di Monte Oliveto, is an ancient church and convent located in piazza Monteoliveto in central Naples, Italy. Across Monteoliveto street from the Fountain in the square is the Renaissance palace of Orsini di Gravina.

Running beneath the Italian city of Naples and the surrounding area is an underground geothermal zone and several tunnels dug during the ages. This geothermal area is present generally from Mount Vesuvius beneath a wide area including Pompei, Herculaneum, and from the volcanic area of Campi Flegrei beneath Naples and over to Pozzuoli and the coastal Baia area. Mining and various infrastructure projects during several millennia have formed extensive caves and underground structures in the zone.

The Catacombs of San Gennaro are underground paleo-Christian burial and worship sites in Naples, Italy, carved out of tuff, a porous stone. They are situated in the northern part of the city, on the slope leading up to Capodimonte, consisting of two levels, San Gennaro Superiore, and San Gennaro Inferiore. The catacombs lie under the Rione Sanità neighborhood of Naples, sometimes called the "Valley of the Dead". The site is now easily identified by the large church of Madre del Buon Consiglio.

In the Age of Revolution, the Lazzaroni of Naples were the poorest of the lower class in the city and Kingdom of Naples. Described as "street people under a chief", they were often depicted as "beggars"—which some actually were, while others subsisted partly by service as messengers, porters, etc. No precise census of them was ever conducted, but contemporaries estimated their total number at around 50,000, and they had a significant role in the social and political life of the city. They were prone to act collectively as crowds and mobs and follow the lead of demagogues, often proving formidable in periods of civil unrest and revolution.

Sant'Angelo a Nilo is a Roman Catholic church located on the Decumano Inferiore in Naples, Italy. It stands diagonally across from San Domenico Maggiore in Naples. It is known for containing the monumental Renaissance-style tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci by Donatello and Michelozzo, one of the major sculptural works in the city.

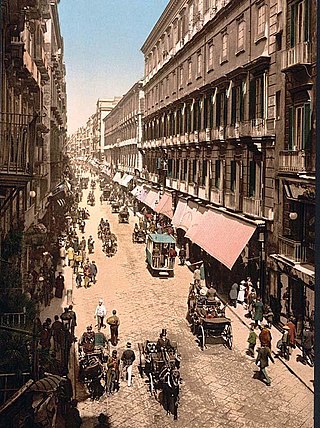

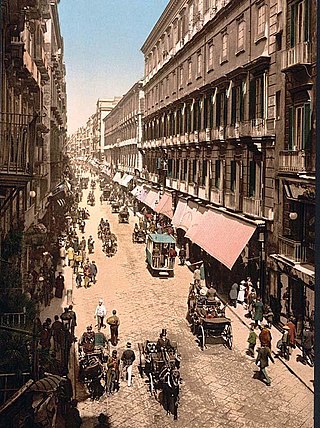

Via Toledo is an ancient street and one of the most important shopping thoroughfares in the city of Naples, Italy. The street is almost 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) long and starts at Piazza Dante and ends in Piazza Trieste e Trento, near Piazza del Plebiscito.

Rione Sanità is a neighbourhood in Naples, part of the Stella quarter. It is located north of Naples' historical centre, adjacent to the Capodimonte hill.

Sant'Agnello Maggiore, also called Sant'Aniello a Caponapoli or Santa Maria Intercede, is a church in the historical center of Naples, Italy.

The Catacombs of Saint Gaudiosus are underground paleo-Christian burial sites, located in the northern area of the city of Naples.

The Poggio Reale villa or Villa Poggio Reale was an Italian Renaissance villa commissioned in 1487 by Alfonso II of Naples as a royal summer residence. The Italian phrase "poggio reale" translates to "royal hill" in English. The villa was designed and built by Giuliano da Maiano and located in the city of Naples, in the district now known as Poggioreale, between the present Via del Campo, Via Santa Maria del Pianto and the new and old Via Poggioreale. At the time it was built, a period when the capital city of the Kingdom of Naples was renowned for elegant homes with expansive vistas of the surrounding landscape and Mount Vesuvius, the villa was outside the city walls of Naples and was one of the most important architectural achievements of the Neapolitan Renaissance. Imitated, admired, robbed of its treasures by another king, left in ruins and partially destroyed, the summer palace of the King of Naples lives on in name as a style.

Giuseppe Chirico, also known as o' Granatiere, was an Italian boss of the Camorra, a Mafia-type organisation in Naples in Italy, at the end of the 19th century.

Biblioteca di Ricerca Area Umanistica (BRAU) is the university library of the Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici of the University of Naples Federico II.

Antonio Ranieri was an Italian writer, patriot and politician, better known for his juvenile intimate friendship with Giacomo Leopardi, the most renowned 19th-century Italian poet.

Maddalena Cerasuolo, also known as Lenuccia, was an Italian patriot and antifascist partisan.

The history of cinema in Naples begins at the end of the 19th century and over time it has recorded cinematographic works, production houses and notable filmmakers. Over the decades, the Neapolitan capital has also been used as a film set for many works, over 600 according to the Internet Movie Database, the first of which would be Panorama of Naples Harbor from 1901.