Construction and facilities

The fortified group Saint-Quentin is one of "detached forts", a concept developed by the engineering lieutenant colonel Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières in France and Hans Alexis von Biehler in Germany. The goal was to form a discontinuous enclosure around Metz with strong artillery batteries spaced with a range of guns. The fortified group spans 77 hectares [4] on a west-facing plateau. With 72 buildings and a built area of 25,600 square meters, it is one of the largest fortified wholes of the first belt. [4] Saint-Quentin was initially not designed as a fortified group, but this resulted from the combination of two strong classical forts, Fort Diou and Fort Girardin. It was partially built by the French between 1868 and 1871 and extensively developed by the Germans between 1872 and 1892. Its topographic position on Mont Saint-Quentin overlooking the city of Metz made it a major strategic position for the French and German staffs. It is separated from Fort de Plappeville by the commune of Lessy.

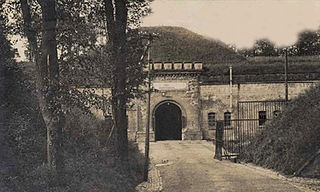

The fortified group Saint-Quentin consists of three parts, the fort Manstein, [note 1] or fort Girardin to the west, Fort Saint-Quentin in the center, and fort Diou, [note 2] or Ostfort, to the East. The fort Diou, trapezoidal, was built by the French from 1868 to 1870 and completed after 1872 by the Prussians. Among the forts of Metz it is the only French work designed by Lieutenant Colonel Séré de Rivières. The fort could accommodate a contingent of 617 men and forty pieces of artillery. Its corners are bastioned and a deep dry moat prohibits access.

On a plateau, Plateau Barracks, or Fort Saint-Quentin covers the junction between the Ostfort and Fort von Manstein. Built between 1872 and 1874, it was surrounded by moats north and south. The Plateau Barracks consists of a principal barracks buried on three sides, a powder magazine and several fortins. These buildings are connected by covered ways, where a rail track of 60 cm wide allows trucks to carry equipment and ammunition. Behind the parapets, many ramps of artillery allow positioning of outdoor artillery.

To the west of the plateau, the Germans built Feste von Manstein from 1872 to 1874 to control the Moselle valley to the south and the neck of Lessy to the north. Pentagonal, Fort von Manstein features a dry moat on three sides. It could accommodate a contingent of more than 600 men and several guns behind its parapets. It also has several observation towers. Work continued until 1898.

Second World War

Bombed several times in 1944, the fortified group of Mont-Saint-Quentin was however not destroyed. Apart from the fort bastion of Diou, and associated structures scattered on the plateau, most of the barracks survived the American bombs quite well. But on the night of August 31 to 1 September 1944, two casemates of the fort, where manuscripts and incunabula from the Metz library had been stored, were burned [5] along with stocks belonging to the German stewardship.

Like the Fort de Plappeville, the Fortified group Driant and the Fortified group Joan of Arc, the fortified group of Mont-Saint-Quentin had its baptism of fire between September and December 1944, during the Battle of Metz. On 3 September 1944, Lieutenant General Walther Krause, then commander of the fortress of Metz, established his combat command post at Fort de Plappeville. [note 6] This fort was in the center of the defenses of Metz, well defended by the fort to the south Manstein (Girardin) held at that time by the SS colonel Joachim von Siegroth. [6] During the three months of fighting, Fort Plappeville, under the command of the artillery Colonel Vogel, and that of Saint-Quentin, successively commanded by Colonels Siegroth Von, Von Richter and Stössel, will cover each other, blocking access by US troops to the valley Moselle, west of Metz. The US offensive launched September 7, 1944 on the west line forts of Metz is cut short. American troops eventually stopped on the Moselle despite taking two bridgeheads south of Metz. The forts, were better defended against them than they had thought, and US troops were figuratively out of breath. General McLain, in agreement with the General Walker, decided to suspend the attacks, pending further plans of the General Staff of the 90 Infantry Division. [7] When hostilities resumed after a rainy month, the soldiers of the 462th Volks-Grenadier-Division still hold firmly the forts of Metz, though supplies are more difficult under artillery fire and frequent bombings. [8]

On November 9, 1944, as a prelude to the assault on Metz, as many as 1,299 heavy bombers, B-17s and B-24s, dump 3,753 tons of bombs, and 1,000 to 2,000 "livres" on fortifications and strategic points in the combat zone of IIIrd army. [9] Most bombers, having dropped bombs without visibility at over 20,000 feet, miss their objectives. In Metz, the 689 loads of bombs dropped on the seven forts of Metz, designated as priority targets, cause merely collateral damage. [10] The underground fortifications, such as the Mont Saint-Quentin, offer good resistance to the American bombings, which include incendiary bombs. Despite the efforts of the combative troops of the 462th Infantry Division, the forts fall one after the other, as a result of fighting or simply running out of food and ammunition. [6]

The final assault on Metz happens at dawn on November 14, 1944. The M101 howitzer from 359th Field Artillery Battalion opened fire on the area located on either side of the Fortified group Jeanne-d'Arc, between the Fort Francis de Guise and the fort Driant to pave the way for 379th Infantry regiment whose goal is to reach the Moselle. The attack is focused on fort Jeanne-d’Arc which ends up being encircled by US troops. After two deadly counterattacks, the men of Major Voss, belonging to the 462th ID return soon to the fortified group Jeanne-d'Arc. In the afternoon of November 15, 1944, the men of 1217th Grenadier-Regiment « Richter », consisting of Security Regiment 1010 and those of 1515th Grenadier-Regiment « Stössel » of the 462e Volksgrenadier division, made several unsuccessful attempts to push the Americans behind the line Canrobert. Under pressure, the German soldiers end up dropping out, leaving behind them many casualties. [11] German grenadiers, who had to withdraw on a line between the point of support Leipzig and the Fort Plappeville finally withdraw in disorder to Metz, leaving only some detachments in the forts. On November 16, 1944, the US attack continues between forts Jeanne D'Arc and Francois de Guise. [11]

On the evening of November 17, 1944, the situation is critical for the commander of the fortress of Metz, General Heinrich Kittel. The men still fighting of Grenadier-Regiment 1215 « Stössel » are now identified in the fortified group of Saint-Quentin. November 18, 1944 378 Infantry Regiment launches the first simultaneous attack on the forts of Saint-Quentin and Fort de Plappeville. On the plateau and in the fort, the men of the 462e Volks-Grenadier-Division were harassed by four days of continuous fighting. Yet they defend every inch on the plateau, bunker by bunker. After a short respite, a second American attack, more deadly than the first, takes the outsides of the fort, forcing the defenders to hide in the precincts of the fort for protection from artillery fire from US troops now ready on the plateau of Plappeville.

On November 19, 1944 378th Infantry Regiment of 95th Infantry Division frontally attack the new Fort de Plappeville and Fort St. Quentin. The attack failed, despite the enthusiasm of US troops. The 378th Infantry regiment is immediately relieved and replaced the next day by the 379th Infantry regiment. Despite the support of continuous gunfire, the forts still resist the attack of the 379th Infantry regiment. On 21 November 1944, the two advanced batteries, located between the fortified group Mont Saint-Quentin and the Fort Plappeville are finally taken, but the forts still resist. An air attack on the two forts is then considered, but it is canceled the same day, for lack of available squadrons. The main objective of the 95th Infantry Division is now the city of Metz, the forts are just surrounded and neutralized by covering fire.

Metz is liberated on November 22, 1944, but the forts Plappeville and St. Quentin still resist for two long weeks in accordance with the orders of the Führer. The fort of St. Quentin, which still had 21 officers, 124 warrant officers and 458 enlisted men, finally surrendered the 6 December 1944 to 5th Infantry division of General Irwin. As night fell on this cold winter day, Colonel von Stossel symbolically submitted his Luger pistol to the commander of 2nd Battalion 11th Infantry regiment, the lieutenant-colonel Dewey B. Gill [12] before leaving in captivity with his men. Fort Plappeville, which had more than 200 men, surrendered the next day, December 7, 1944.

The fort Jeanne-d’Arc was the last of the forts of Metz to disarm, on December 13, 1944. Determined German resistance, bad weather and floods, inopportunity, and a general tendency to underestimate the firepower of the fortifications of Metz, helped slow the US offensive, giving the opportunity to the German Army to withdraw in good order to the Saarland. [13] The objective of the German staff, which was to stall the US troops at Metz for the longest possible time before they could reach the front of the Siegfried Line, was largely achieved.