Otto IV was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1209 until his death in 1218.

Frederick Barbarossa, also known as Frederick I, was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 1152. He was crowned King of Italy on 24 April 1155 in Pavia and emperor by Pope Adrian IV on 18 June 1155 in Rome. Two years later, the term sacrum ("holy") first appeared in a document in connection with his empire. He was later formally crowned King of Burgundy, at Arles on 30 June 1178. He was named Barbarossa by the northern Italian cities which he attempted to rule: Barbarossa means "red beard" in Italian; in German, he was known as Kaiser Rotbart, which in English means "Emperor Redbeard". The prevalence of the Italian nickname, even in later German usage, reflects the centrality of the Italian campaigns under his reign.

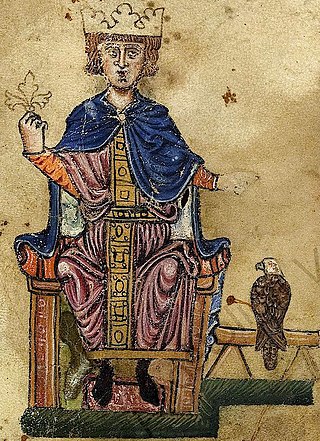

Frederick II was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of Emperor Henry VI of the Hohenstaufen dynasty and Queen Constance I of Sicily of the Hauteville dynasty.

William II was the Count of Holland and Zeeland from 1234 until his death. He was elected anti-king of Germany in 1248 and ruled as sole king from 1254 onwards.

The Guelphs and Ghibellines were factions supporting respectively the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy during the Middle Ages. During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalry between these two parties dominated political life across medieval Italy. The struggle for power between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire arose with the Investiture Controversy, which began in 1075 and ended with the Concordat of Worms in 1122.

Stefan Anton George was a German symbolist poet and a translator of Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Hesiod, and Charles Baudelaire. He is also known for his role as leader of the highly influential literary circle called the George-Kreis and for founding the literary magazine Blätter für die Kunst.

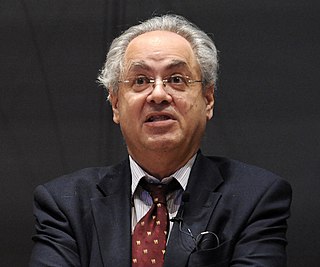

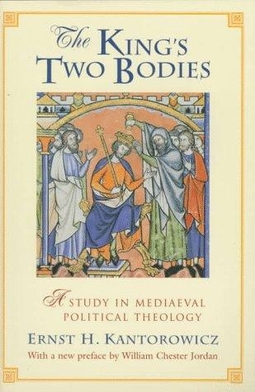

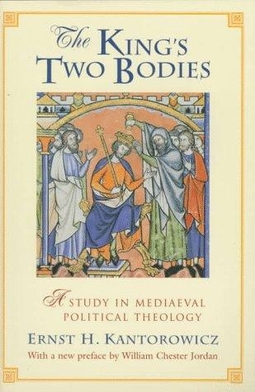

Ernst Hartwig Kantorowicz was a German historian of medieval political and intellectual history and art, known for his 1927 book Kaiser Friedrich der Zweite on Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, and The King's Two Bodies (1957) on medieval and early modern ideologies of monarchy and the state. He was an elected member of both the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The Battle of Parma was fought on 18 February 1248 between the forces of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and the Lombard League. The Guelphs attacked the Imperial camp when Frederick II was away. The Imperial forces were defeated and much of Frederick's treasure was lost.

Carl Erdmann was a German historian who specialized in medieval political and intellectual history. He is noted in particular for his study of the origins of the idea of crusading in medieval Latin Christendom, as well as his work on letter collections and correspondence among secular and ecclesiastical elites in the eleventh century. He is often mentioned alongside Percy Ernst Schramm and Ernst H. Kantorowicz as one of the most influential and important German scholars of medieval political culture in the twentieth century. His promising and remarkably prolific career was cut short by his death in the German army at the end of World War II.

Percy Ernst Schramm was a German historian who specialized in art history and medieval history. Schramm was a Chair and Professor of History at the University of Göttingen from 1929 to 1963.

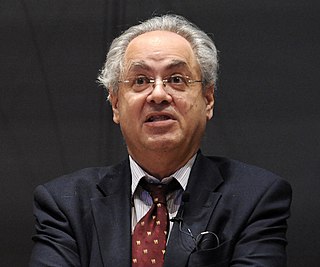

David Samuel Harvard Abulafia is an English historian with a particular interest in Italy, Spain and the rest of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. He spent most of his career at the University of Cambridge, rising to become a professor at the age of 50. He retired in 2017 as Professor Emeritus of Mediterranean History. He is a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He was Chairman of the History Faculty at Cambridge University, 2003-5, and was elected a member of the governing Council of Cambridge University in 2008. He is visiting Beacon Professor at the new University of Gibraltar, where he also serves on the Academic Board. He is a visiting professor at the College of Europe.

Robert E. Lerner is an American medieval historian and professor of history emeritus at Northwestern University.

Alamanno da Costa was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of Syracuse in the Kingdom of Sicily, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstanding conflict with Pisa and in the origin of its conflict with Venice. The historian Ernst Kantorowicz called him a "famous prince of pirates".

Gertrud Kantorowicz (1876-1945) was a German art historian, poet and translator.

The King's Two Bodies is a 1957 historical book by Ernst Kantorowicz. It concerns medieval political theology and the distinctions separating the "body natural" and the "body politic".

Emilie Kiep-Altenloh (1888–1985) was a German sociologist and politician.

Swabian Sicily denotes the period in the history of Sicily during which it was ruled by the Hohenstaufen dynasty, lasting from Henry VI's's accession to the island's throne in 1194 until Manfred of Sicily's defeat by Charles I of Anjou in 1266. It has been particularly researched by German scholars such as Ernst Kantorowicz and Willy Cohn.

Ruggero de Amicis was a Sicilian high administrator and diplomat under the Emperor Frederick II. He served as justiciar of western Sicily between 1239 and 1240, then as captain and master justiciar of all Sicily and Calabria from 1240 until 1241. He was Frederick's ambassador to Ayyubid Egypt from 1241 until 1242. He was also active as a vernacular lyric poet, one of the earliest members of the Sicilian school. In 1246, he joined a conspiracy against the emperor and was arrested. He died in prison.

Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, also called Stupor mundi, was a notable European ruler who left a controversial political and cultural legacy. Considered by some to be "the most brilliant of medieval German monarchs, and probably of all medieval rulers", and admired for his multifaceted activities in the fields of government building, legislative work, cultural patronage and science, he has also been criticized for his cruelty and despotism.

Theodor Ernst "Ted" Mommsen was a German historian of medieval cultural and intellectual history with wide-ranging scholarly interests, from the church father Augustine of Hippo to the early Renaissance poet Petrarch. He was the grandson, and namesake, of the renowned Roman historian Theodor Mommsen. Mommsen began his academic career in Germany but emigrated to the United States in 1936 to escape Nazism.