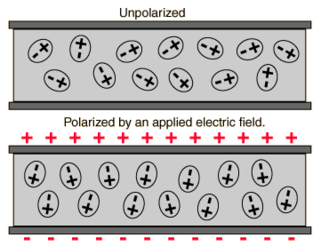

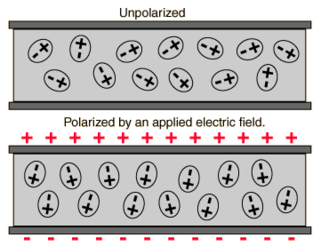

In electromagnetism, the absolute permittivity, often simply called permittivity and denoted by the Greek letter ε (epsilon), is a measure of the electric polarizability of a dielectric material. A material with high permittivity polarizes more in response to an applied electric field than a material with low permittivity, thereby storing more energy in the material. In electrostatics, the permittivity plays an important role in determining the capacitance of a capacitor.

Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) is the differential absorption of left and right circularly polarized light, induced in a sample by a strong magnetic field oriented parallel to the direction of light propagation. MCD measurements can detect transitions which are too weak to be seen in conventional optical absorption spectra, and it can be used to distinguish between overlapping transitions. Paramagnetic systems are common analytes, as their near-degenerate magnetic sublevels provide strong MCD intensity that varies with both field strength and sample temperature. The MCD signal also provides insight into the symmetry of the electronic levels of the studied systems, such as metal ion sites.

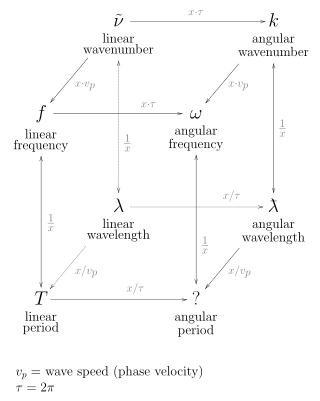

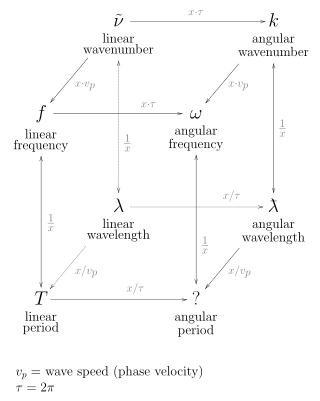

In the physical sciences, the wavenumber, also known as repetency, is the spatial frequency of a wave, measured in cycles per unit distance or radians per unit distance. It is analogous to temporal frequency, which is defined as the number of wave cycles per unit time or radians per unit time.

In optical physics, transmittance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in transmitting radiant energy. It is the fraction of incident electromagnetic power that is transmitted through a sample, in contrast to the transmission coefficient, which is the ratio of the transmitted to incident electric field.

In the physical sciences and electrical engineering, dispersion relations describe the effect of dispersion on the properties of waves in a medium. A dispersion relation relates the wavelength or wavenumber of a wave to its frequency. Given the dispersion relation, one can calculate the frequency-dependent phase velocity and group velocity of each sinusoidal component of a wave in the medium, as a function of frequency. In addition to the geometry-dependent and material-dependent dispersion relations, the overarching Kramers–Kronig relations describe the frequency-dependence of wave propagation and attenuation.

In quantum physics, Fermi's golden rule is a formula that describes the transition rate from one energy eigenstate of a quantum system to a group of energy eigenstates in a continuum, as a result of a weak perturbation. This transition rate is effectively independent of time and is proportional to the strength of the coupling between the initial and final states of the system as well as the density of states. It is also applicable when the final state is discrete, i.e. it is not part of a continuum, if there is some decoherence in the process, like relaxation or collision of the atoms, or like noise in the perturbation, in which case the density of states is replaced by the reciprocal of the decoherence bandwidth.

In atomic, molecular, and optical physics, the Einstein coefficients are quantities describing the probability of absorption or emission of a photon by an atom or molecule. The Einstein A coefficients are related to the rate of spontaneous emission of light, and the Einstein B coefficients are related to the absorption and stimulated emission of light. Throughout this article, "light" refers to any electromagnetic radiation, not necessarily in the visible spectrum.

In solid-state physics, the nearly free electron model is a quantum mechanical model of physical properties of electrons that can move almost freely through the crystal lattice of a solid. The model is closely related to the more conceptual empty lattice approximation. The model enables understanding and calculation of the electronic band structures, especially of metals.

The Franz–Keldysh effect is a change in optical absorption by a semiconductor when an electric field is applied. The effect is named after the German physicist Walter Franz and Russian physicist Leonid Keldysh.

When an electromagnetic wave travels through a medium in which it gets attenuated, it undergoes exponential decay as described by the Beer–Lambert law. However, there are many possible ways to characterize the wave and how quickly it is attenuated. This article describes the mathematical relationships among:

Surface-extended X-ray absorption fine structure (SEXAFS) is the surface-sensitive equivalent of the EXAFS technique. This technique involves the illumination of the sample by high-intensity X-ray beams from a synchrotron and monitoring their photoabsorption by detecting in the intensity of Auger electrons as a function of the incident photon energy. Surface sensitivity is achieved by the interpretation of data depending on the intensity of the Auger electrons instead of looking at the relative absorption of the X-rays as in the parent method, EXAFS.

Defect types include atom vacancies, adatoms, steps, and kinks that occur most frequently at surfaces due to the finite material size causing crystal discontinuity. What all types of defects have in common, whether surface or bulk defects, is that they produce dangling bonds that have specific electron energy levels different from those of the bulk. This difference occurs because these states cannot be described with periodic Bloch waves due to the change in electron potential energy caused by the missing ion cores just outside the surface. Hence, these are localized states that require separate solutions to the Schrödinger equation so that electron energies can be properly described. The break in periodicity results in a decrease in conductivity due to defect scattering.

Kramers' law is a formula for the spectral distribution of X-rays produced by an electron hitting a solid target. The formula concerns only bremsstrahlung radiation, not the element specific characteristic radiation. It is named after its discoverer, the Dutch physicist Hendrik Anthony Kramers.

The Monte Carlo method for electron transport is a semiclassical Monte Carlo (MC) approach of modeling semiconductor transport. Assuming the carrier motion consists of free flights interrupted by scattering mechanisms, a computer is utilized to simulate the trajectories of particles as they move across the device under the influence of an electric field using classical mechanics. The scattering events and the duration of particle flight is determined through the use of random numbers.

Heat transfer physics describes the kinetics of energy storage, transport, and energy transformation by principal energy carriers: phonons, electrons, fluid particles, and photons. Heat is thermal energy stored in temperature-dependent motion of particles including electrons, atomic nuclei, individual atoms, and molecules. Heat is transferred to and from matter by the principal energy carriers. The state of energy stored within matter, or transported by the carriers, is described by a combination of classical and quantum statistical mechanics. The energy is different made (converted) among various carriers. The heat transfer processes are governed by the rates at which various related physical phenomena occur, such as the rate of particle collisions in classical mechanics. These various states and kinetics determine the heat transfer, i.e., the net rate of energy storage or transport. Governing these process from the atomic level to macroscale are the laws of thermodynamics, including conservation of energy.

The semiconductor Bloch equations describe the optical response of semiconductors excited by coherent classical light sources, such as lasers. They are based on a full quantum theory, and form a closed set of integro-differential equations for the quantum dynamics of microscopic polarization and charge carrier distribution. The SBEs are named after the structural analogy to the optical Bloch equations that describe the excitation dynamics in a two-level atom interacting with a classical electromagnetic field. As the major complication beyond the atomic approach, the SBEs must address the many-body interactions resulting from Coulomb force among charges and the coupling among lattice vibrations and electrons.

The semiconductor luminescence equations (SLEs) describe luminescence of semiconductors resulting from spontaneous recombination of electronic excitations, producing a flux of spontaneously emitted light. This description established the first step toward semiconductor quantum optics because the SLEs simultaneously includes the quantized light–matter interaction and the Coulomb-interaction coupling among electronic excitations within a semiconductor. The SLEs are one of the most accurate methods to describe light emission in semiconductors and they are suited for a systematic modeling of semiconductor emission ranging from excitonic luminescence to lasers.

The Elliott formula describes analytically, or with few adjustable parameters such as the dephasing constant, the light absorption or emission spectra of solids. It was originally derived by Roger James Elliott to describe linear absorption based on properties of a single electron–hole pair. The analysis can be extended to a many-body investigation with full predictive powers when all parameters are computed microscopically using, e.g., the semiconductor Bloch equations or the semiconductor luminescence equations.

The interaction of matter with light, i.e., electromagnetic fields, is able to generate a coherent superposition of excited quantum states in the material. Coherent denotes the fact that the material excitations have a well defined phase relation which originates from the phase of the incident electromagnetic wave. Macroscopically, the superposition state of the material results in an optical polarization, i.e., a rapidly oscillating dipole density. The optical polarization is a genuine non-equilibrium quantity that decays to zero when the excited system relaxes to its equilibrium state after the electromagnetic pulse is switched off. Due to this decay which is called dephasing, coherent effects are observable only for a certain temporal duration after pulsed photoexcitation. Various materials such as atoms, molecules, metals, insulators, semiconductors are studied using coherent optical spectroscopy and such experiments and their theoretical analysis has revealed a wealth of insights on the involved matter states and their dynamical evolution.

The Wannier equation describes a quantum mechanical eigenvalue problem in solids where an electron in a conduction band and an electronic vacancy within a valence band attract each other via the Coulomb interaction. For one electron and one hole, this problem is analogous to the Schrödinger equation of the hydrogen atom; and the bound-state solutions are called excitons. When an exciton's radius extends over several unit cells, it is referred to as a Wannier exciton in contrast to Frenkel excitons whose size is comparable with the unit cell. An excited solid typically contains many electrons and holes; this modifies the Wannier equation considerably. The resulting generalized Wannier equation can be determined from the homogeneous part of the semiconductor Bloch equations or the semiconductor luminescence equations.

1. H. Haug and S. W. Koch, " ", World Scientific (1994). sec.5.4 a