Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through a constitution or other legal protection and security. It is in opposition to paid press, where communities, police organizations, and governments are paid for their copyrights.

Reporters Without Borders is an international non-profit and non-governmental organization headquartered in Paris, which focuses on safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its advocacy as founded on the belief that everyone requires access to the news and information, in line with Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that recognises the right to receive and share information regardless of frontiers, along with other international rights charters. RSF has consultative status at the United Nations, UNESCO, the Council of Europe, and the International Organisation of the Francophonie.

In Taiwan, censorship involves the suppression of speech or public communication and raises issues of freedom of speech, which is protected by Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of China. There exist a number of cases where freedom of speech is restricted by the law, which include defamation, breach of privacy, infringement of copyright, pornography, incitement to commit crimes, sale of prohibited items and distribution of offensive or distributing content.

Censorship in Bhutan refers to the way in which the Government of Bhutan controls information within its borders. There are no laws that either guarantee citizens' right to information or explicitly structure a censorship scheme. However, censorship in Bhutan is still conducted by restrictions on the ownership of media outlets, licensing of journalists, and the blocking of websites.

Censorship in Thailand involves the strict control of political news under successive governments, including by harassment and manipulation.

Censorship in Israel is officially carried out by the Israeli Military Censor, a unit in the Israeli government officially tasked with carrying out preventive censorship regarding the publication of information that might affect the security of Israel. The body is headed by the Israeli Chief Censor, a military official appointed by Israel's Minister of Defense, who bestows upon the Chief Censor the authority to suppress information he deems compromising from being made public in the media, such as Israel's nuclear weapons program and Israel's military operations outside its borders. On average, 2240 press articles in Israel are censored by the Israeli Military Censor each year, approximately 240 of which in full, and around 2000 partially.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Bhutan face legal challenges that are not faced by non-LGBTQ people. Bhutan does not provide any anti-discrimination laws for LGBT people, and same-sex unions are not recognised. However, same-sex sexual activity was decriminalised in Bhutan on 17 February 2021.

The Constitution of India provides the right to freedom, given in article 19 with the view of guaranteeing individual rights that were considered vital by the framers of the constitution. The right to freedom in Article 19 guarantees the freedom of speech and expression, as one of its six freedoms.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

Human rights in Bhutan are those outlined in Article 7 of its Constitution. The Royal Government of Bhutan has affirmed its commitment to the "enjoyment of all human rights" as integral to the achievement of 'gross national happiness' (GNH); the unique principle which Bhutan strives for, as opposed to fiscally based measures such as GDP.

Censorship in Bangladesh refers to the government censorship of the press and infringement of freedom of speech. Article 39 of the constitution of Bangladesh protects free speech.

Censorship in Armenia is generally non-existent, except in some limited incidents.

Censorship in Mexico includes all types of suppression of free speech in Mexico. This includes all efforts to destroy or obscure information and access to it spanning from the nation's colonial Spanish roots to the present. In 2016, Reporters Without Borders ranked Mexico 149 out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index, declaring Mexico to be “the world's most dangerous country for journalists.” Additionally, in 2010 the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that Mexico was "one of the worst nations in solving crimes against journalists." Under the current Mexican Constitution, both freedom of information and expression are to be protected under the legislation from Article 6, which states that "the expression of ideas shall not be subject to any judicial or administrative investigation, unless it offends good morals, infringes the rights of others, incites to crime, or disturbs the public order," and Article 7 which guarantees that "freedom of writing and publishing writings on any subject is inviolable. No law or authority may establish censorship, require bonds from authors or printers, or restrict the freedom of printing, which shall be limited only by the respect due to private life, morals, and public peace." Mexico is currently a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which gives them the responsibility to uphold these established laws regarding freedom of expression.

Censorship in Ecuador refers to all actions which can be considered as suppression in speech in Ecuador. In the Freedom of the Press Report 2016 by Freedom House, the press in Ecuador is classified as "not free". The 2016 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders placed Ecuador in the "noticeable problems" category for press freedom, ranking the country 109 out of 180.

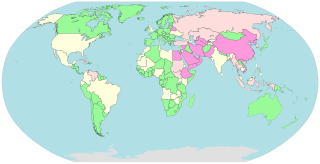

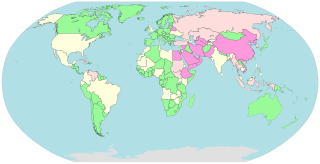

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.

Freedom of the press in China refers to the journalism standards and its freedom and censorship exercised by the government of China. The Constitution of the People's Republic of China guarantees "freedom of speech [and] of the press" which the government, in practice, routinely violates with total impunity, according to Reporters Without Borders.

Freedom of the press in India is legally protected by the Amendment to the constitution of India, while the sovereignty, national integrity, and moral principles are generally protected by the law of India to maintain a hybrid legal system for independent journalism. In India, media bias or misleading information is restricted under the certain constitutional amendments as described by the country's constitution. The media crime is covered by the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which is applicable to all substantive aspects of criminal law.

Freedom of the press in Bangladesh refers to the censorship and endorsement on public opinions, fundamental rights, freedom of expression, human rights, explicitly mass media such as the print, broadcast and online media as described or mentioned in the constitution of Bangladesh. The country's press is legally regulated by the certain amendments, while the sovereignty, national integrity and sentiments are generally protected by the law of Bangladesh to maintain a hybrid legal system for independent journalism and to protect fundamental rights of the citizens in accordance with secularism and media law. In Bangladesh, media bias and disinformation is restricted under the certain constitutional amendments as described by the country's post-independence constitution.

Freedom of the press in Myanmar refers to the freedom of speech, expression, right to information, and mass media in particular. The media of Myanmar is regulated by the law of Myanmar, the News Media Law which prevent spreading or circulating media bias. It also determines freedom of expression for media houses, journalists, and other individuals or organisations working within the country. Its print, broadcast and Internet media is regulated under the News Media Law, nominally compiled by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and international standards on freedom of expression.

Namgay Zam is a Bhutanese journalist and activist. Having made her name as a producer and anchor on the public Bhutan Broadcasting Service, she served from 2019 to 2023 as executive director of the Journalists' Association of Bhutan. A 2016 lawsuit against Zam was considered the first test case of the country's press freedoms after its democratic transition.