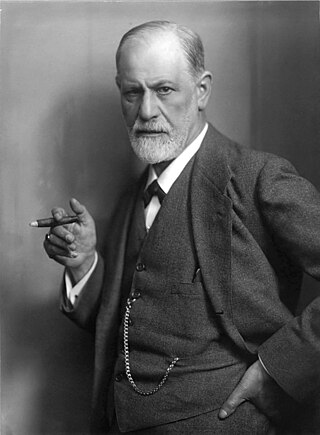

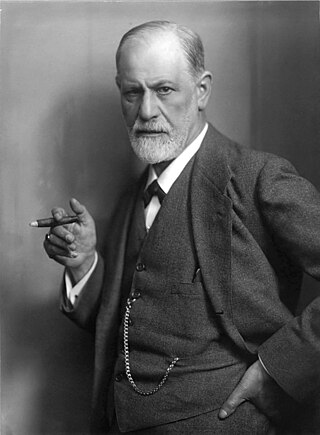

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

Susan Lee Sontag was an American writer, critic, and public intellectual. She mostly wrote essays, but also published novels; she published her first major work, the essay "Notes on 'Camp' ", in 1964. Her best-known works include the critical works Against Interpretation (1966), On Photography (1977), Illness as Metaphor (1978) and Regarding the Pain of Others, as well as the fictional works The Way We Live Now (1986), The Volcano Lover (1992), and In America (1999).

David Rieff is an American nonfiction writer and policy analyst. His books have focused on issues of immigration, international conflict, and humanitarianism.

Robert Christopher Lasch was an American historian, moralist and social critic who was a history professor at the University of Rochester. He sought to use history to demonstrate what he saw as the pervasiveness with which major institutions, public and private, were eroding the competence and independence of families and communities. Lasch strove to create a historically informed social criticism that could teach Americans how to deal with rampant consumerism, proletarianization, and what he famously labeled "the culture of narcissism".

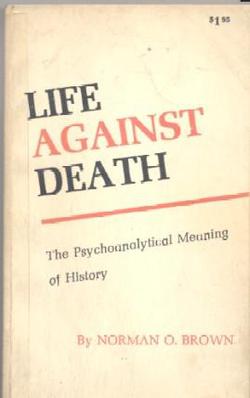

Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History is a book by the American classicist Norman O. Brown, in which the author offers a radical analysis and critique of the work of Sigmund Freud, tries to provide a theoretical rationale for a nonrepressive civilization, explores parallels between psychoanalysis and Martin Luther's theology, and draws on revolutionary themes in western religious thought, especially the body mysticism of Jakob Böhme and William Blake. It was the result of an interest in psychoanalysis that began when the philosopher Herbert Marcuse suggested to Brown that he should read Freud.

Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud is a book by the German philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the theories of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, and explores the potential of collective memory to be a source of disobedience and revolt and point the way to an alternative future. Its title alludes to Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). The 1966 edition has an added "political preface".

Salmagundi is a US quarterly periodical, featuring cultural criticism, fiction, and poetry, along with transcripts of symposia and interviews with prominent writers and intellectuals. Susan Sontag, a longtime friend of the publication, referred to it as "simply my favorite little magazine." In The Book Wars, James Atlas writes that Salmagundi is "perhaps the country's leading journal of intellectual opinion."

Philip Rieff was an American sociologist and cultural critic, who taught sociology at the University of Pennsylvania from 1961 until 1992, and also, during the 1950s, at the University of Chicago, where he met Susan Sontag. He was the author of a number of books on Sigmund Freud and his legacy, including Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959) and The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith after Freud (1966). He married his 17-year-old student Susan Sontag after 10 days of courtship in the 1950s. The marriage lasted eight years during which their son, David Rieff—a writer and editor of his mother's personal journals—was born. His second wife and widow Alison Douglas Knox died December 12, 2011.

Knowledge and Human Interests is a 1968 book by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author discusses the development of the modern natural and human sciences. He criticizes Sigmund Freud, arguing that psychoanalysis is a branch of the humanities rather than a science, and provides a critique of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis is a book by Richard Webster, in which the author provides a critique of Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis, and attempts to develop his own theory of human nature. Webster argues that Freud became a kind of Messiah and that psychoanalysis is a pseudoscience and a disguised continuation of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. Webster endorses Gilbert Ryle's arguments against mentalist philosophies in The Concept of Mind (1949), and criticizes many other authors for their treatment of Freud and psychoanalysis.

The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory is a book by the former psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, in which the author argues that Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, deliberately suppressed his early hypothesis, known as the seduction theory, that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse during infancy, because he refused to believe that children are the victims of sexual violence and abuse within their own families. Masson reached this conclusion while he had access to several of Freud's unpublished letters as projects director of the Sigmund Freud Archives. The Assault on Truth was first published in 1984 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux; several revised editions have since been published.

Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend is a 1979 biography of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, by the psychologist Frank Sulloway.

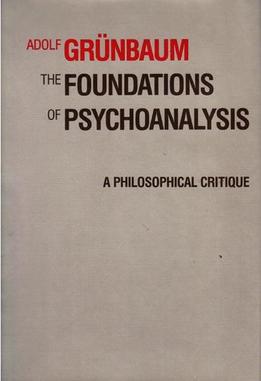

The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique is a 1984 book by the philosopher Adolf Grünbaum, in which the author offers a philosophical critique of the work of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The book was first published in the United States by the University of California Press. Grünbaum evaluates the status of psychoanalysis as a natural science, criticizes the method of free association and Freud's theory of dreams, and discusses the psychoanalytic theory of paranoia. He argues that Freud, in his efforts to defend psychoanalysis as a method of clinical investigation, employed an argument that Grünbaum refers to as the "Tally Argument"; according to Grünbaum, it rests on the premises that only psychoanalysis can provide patients with correct insight into the unconscious pathogens of their psychoneuroses and that such insight is necessary for successful treatment of neurotic patients. Grünbaum argues that the argument suffers from major problems. Grünbaum also criticizes the views of psychoanalysis put forward by other philosophers, including the hermeneutic interpretations propounded by Jürgen Habermas and Paul Ricœur, as well as Karl Popper's position that psychoanalytic propositions cannot be disconfirmed and that psychoanalysis is therefore a pseudoscience.

Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation is a 1965 book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, written by the French philosopher Paul Ricœur. In Freud and Philosophy, Ricœur interprets Freudian work in terms of hermeneutics, a theory that governs the interpretation of a particular text, and phenomenology, a school of philosophy founded by Edmund Husserl. Ricœur addresses questions such as the nature of interpretation in psychoanalysis, the understanding of human nature and the relationship between Freud's interpretation of culture amongst other interpretations. The book was first published in France by Éditions du Seuil, and in the United States by Yale University Press.

The Memory Wars: Freud's Legacy in Dispute is a 1995 book that reprints articles by the critic Frederick Crews critical of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and recovered-memory therapy. It also reprints letters from Harold P. Blum, Marcia Cavell, Morris Eagle, Matthew Erdelyi, Allen Esterson, Robert R. Holt, James Hopkins, Lester Luborsky, David D. Olds, Mortimer Ostow, Bernard L. Pacella, Herbert S. Peyser, Charlotte Krause Prozan, Theresa Reid, James L. Rice, Jean Schimek, and Marian Tolpin.

Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire is a book by the psychologist Hans Eysenck, in which the author criticizes Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Eysenck argues that psychoanalysis is unscientific. The book received both positive and negative reviews. Eysenck has been criticized for his discussion of the physician Josef Breuer's treatment of his patient Anna O., whom Eysenck argues suffered from tuberculous meningitis.

Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist is a book about the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche by the philosopher Walter Kaufmann. The book, first published by Princeton University Press, was influential and is considered a classic study. Kaufmann has been credited with helping to transform Nietzsche's reputation after World War II by dissociating him from Nazism, and making it possible for Nietzsche to be taken seriously as a philosopher. However, Kaufmann has been criticized for presenting Nietzsche as an existentialist, and for other details of his interpretation.

The Freudian Fallacy, first published in the United Kingdom as Freud and Cocaine, is a 1983 book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, by the medical historian Elizabeth M. Thornton, in which the author argues that Freud became a cocaine addict and that his theories resulted from his use of cocaine. The book received several negative reviews, and some criticism from historians, but has been praised by authors critical of Freud and psychoanalysis. The work has been compared to Jeffrey Masson's The Assault on Truth (1984).

Philosophical Essays on Freud is a 1982 anthology of articles about Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis edited by the philosophers Richard Wollheim and James Hopkins. Published by Cambridge University Press, it includes an introduction from Hopkins and an essay from Wollheim, as well as selections from philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, Clark Glymour, Adam Morton, Stuart Hampshire, Brian O'Shaughnessy, Jean-Paul Sartre, Thomas Nagel, and Donald Davidson. The essays deal with philosophical questions raised by the work of Freud, including topics such as materialism, intentionality, and theories of the self's structure. They represent a range of different viewpoints, most of them from within the tradition of analytic philosophy. The book received a mixture of positive, mixed, and negative reviews. Commentators found the contributions included in the book to be of uneven value.

Sontag: Her Life and Work is a 2019 biography of American writer Susan Sontag written by Benjamin Moser.