Medieval warfare is the warfare of the Middle Ages. Technological, cultural, and social advancements had forced a severe transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity, changing military tactics and the role of cavalry and artillery. In terms of fortification, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of the castle in Europe, which then spread to the Holy Land.

A trireme( TRY-reem; derived from Latin: trirēmis "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek triērēs, literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Romans.

The Battle of the Lipari Islands or Battle of Lipara was a naval encounter fought in 260 BC during the First Punic War. A squadron of 20 Carthaginian ships commanded by Boödes surprised 17 Roman ships under the senior consul for the year Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio in Lipara Harbour. The inexperienced Romans made a poor showing, with all 17 of their ships captured, along with their commander.

The Battle of Cape Ecnomus or Eknomos was a naval battle, fought off southern Sicily, in 256 BC, between the fleets of Carthage and the Roman Republic, during the First Punic War. It was the largest battle of the war and one of the largest naval battles in history. The Carthaginian fleet was commanded by Hanno and Hamilcar; the Roman fleet jointly by the consuls for the year, Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius Vulso Longus. It resulted in a clear victory for the Romans.

The naval Battle of Drepana took place in 249 BC during the First Punic War near Drepana in western Sicily, between a Carthaginian fleet under Adherbal and a Roman fleet commanded by Publius Claudius Pulcher.

The Battle of the Aegates was a naval battle fought on 10 March 241 BC between the fleets of Carthage and Rome during the First Punic War. It took place among the Aegates Islands, off the western coast of the island of Sicily. The Carthaginians were commanded by Hanno, and the Romans were under the overall authority of Gaius Lutatius Catulus, but Quintus Valerius Falto commanded during the battle. It was the final and deciding battle of the 23-year-long First Punic War.

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, superseding the trireme and transforming naval warfare. Ships became increasingly large and heavy, including some of the largest wooden ships hitherto constructed. These developments were spearheaded in the Hellenistic Near East, but also to a large extent shared by the naval powers of the Western Mediterranean, specifically Carthage and the Roman Republic. While the wealthy successor kingdoms in the East built huge warships ("polyremes"), Carthage and Rome, in the intense naval antagonism during the Punic Wars, relied mostly on medium-sized vessels. At the same time, smaller naval powers employed an array of small and fast craft, which were also used by the ubiquitous pirates. Following the establishment of complete Roman hegemony in the Mediterranean after the Battle of Actium, the nascent Roman Empire faced no major naval threats. In the 1st century AD, the larger warships were retained only as flagships and were gradually supplanted by the light liburnians until, by Late Antiquity, the knowledge of their construction had been lost.

A Geobukseon, also known as turtle ship in western descriptions, was a type of large Korean warship that was used intermittently by the Royal Korean Navy during the Joseon dynasty from the early 15th century up until the 19th century. It was used alongside the panokseon warships in the fight against invading Japanese naval ships. The ship's name derives from its protective shell-like covering. One of a number of pre-industrial armoured ships developed in Europe and in East Asia, this design has been described by some as the first armored ship in the world.

A dromon was a type of galley and the most important warship of the Byzantine navy from the 5th to 12th centuries AD, when they were succeeded by Italian-style galleys. It was developed from the ancient liburnian, which was the mainstay of the Roman navy during the Empire.

The naval forces of the ancient Roman state were instrumental in the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean Basin, but it never enjoyed the prestige of the Roman legions. Throughout their history, the Romans remained a primarily land-based people and relied partially on their more nautically inclined subjects, such as the Greeks and the Egyptians, to build their ships. Because of that, the navy was never completely embraced by the Roman state, and deemed somewhat "un-Roman".

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard. Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used in favorable winds, but human effort was always the primary method of propulsion. This allowed galleys to navigate independently of winds and currents. The galley originated among the seafaring civilizations around the Mediterranean Sea in the late second millennium BC and remained in use in various forms until the early 19th century in warfare, trade, and piracy.

The Byzantine navy was the naval force of the East Roman or Byzantine Empire. Like the empire it served, it was a direct continuation from its Imperial Roman predecessor, but played a far greater role in the defence and survival of the state than its earlier iteration. While the fleets of the unified Roman Empire faced few great naval threats, operating as a policing force vastly inferior in power and prestige to the legions, the sea became vital to the very existence of the Byzantine state, which several historians have called a "maritime empire".

Panokseon was an oar and sail propelled ship that was the main class of warship used by Joseon during the late 16th century. The first ship of this class was constructed in 1555. It was a ship made of sturdy pine wood, and was instrumental in the victories over the numerically superior Japanese Navy during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98). Admiral Yi Sun-sin (1545–1598) of the Joseon navy employed them alongside turtle ships during the war with great success.

Sailing ship tactics were the naval tactics employed by sailing ships in contrast to galley tactics employed by oared vessels. This article focuses on the period from c. 1500 to the mid-19th century, when sailing warships were replaced with steam-powered ironclads.

Naval boarding action is an offensive tactic used in naval warfare to come up against an enemy marine vessel and attack by inserting combatants aboard that vessel. The goal of boarding is to invade and overrun the enemy personnel on board in order to capture, sabotage or destroy the enemy vessel. While boarding attacks were originally carried out by ordinary sailors who are proficient in hand-to-hand combat, larger warships often deploy specially trained and equipped regular troops such as marines and special forces as boarders. Boarding and close quarters combat had been a primary means to conclude a naval battle since antiquity, until the early modern period when heavy naval guns gained tactical primacy at sea.

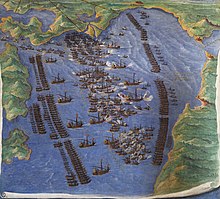

Galleasses were military ships developed from large merchant galleys, and intended to combine galley speed with the sea-worthiness and artillery of a galleon. While perhaps never quite matching up to their full expectations, galleasses nevertheless remained significant elements in the early modern naval armoury from the 15th to 17th centuries.

The Greek navy functioned much like the ancient Greek army. Several similarities existed between them, suggesting that the mindset of the Greeks flowed naturally between the two forms of fighting. The Greeks' success on land easily translated onto the sea. Greek naval actions always took place near the land so they could easily return to land to eat and to sleep, and allowing the Greek ships to stick to narrow waters to out-maneuver the opposing fleet. It was not uncommon for ships to beach and battle on land as well. Developing new techniques for the revolutionary trireme, and staying true to their land-based roots, the Greeks soon became a force to be reckoned with on the sea during the 5th century. They were also one of the greatest armies/naval forces in ancient times.

The Venetian navy was the navy of the Venetian Republic which played an important role in the history of the republic and the Mediterranean world. It was the premier navy in the Mediterranean Sea for many centuries between the medieval and early modern periods, providing Venice with control and influence over trade and politics far in excess of the republic's size and population. It was one of the first navies to mount gunpowder weapons aboard ships, and through an organised system of naval dockyards, armouries and chandlers was able to continually keep ships at sea and rapidly replace losses. The Venetian Arsenal was one of the greatest concentrations of industrial capacity prior to the Industrial Revolution and responsible for the bulk of the republic's naval power.

The Roman withdrawal from Africa was the attempt by the Roman Republic in 255 BC to rescue the survivors of their defeated expeditionary force to Carthaginian Africa during the First Punic War. A large fleet commanded by Servius Fulvius Paetinus Nobilior and Marcus Aemilius Paullus successfully evacuated the survivors after defeating an intercepting Carthaginian fleet, but was struck by a storm while returning, losing most of its ships.

The Battle of Capo d'Orso, sometimes known as the Battle of Cava and the Battle of Amalfi was a naval engagement taking place over two days, on April 28 and April 29, 1528. A French fleet inflicted a crushing defeat on the fleet of the Kingdom of Naples under Spanish control in the Gulf of Salerno, where the Spanish forces sailing southwards from their naval station in Naples trying to break the French blockade of the city met the French fleet.