Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia, although some lizards are more closely related to these two excluded groups than they are to other lizards. Lizards range in size from chameleons and geckos a few centimeters long to the 3-meter-long Komodo dragon.

Reptiles, in common parlance, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic ('cold-blooded') metabolism and amniotic development. Living reptiles comprise four orders: Testudines (turtles), Crocodilia (crocodilians), Squamata, and Rhynchocephalia. As of May 2023, about 12,000 living species of reptiles are listed in the Reptile Database. The study of the traditional reptile orders, customarily in combination with the study of modern amphibians, is called herpetology.

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, courtship, and feeding young. The terms beak and rostrum are also used to refer to a similar mouth part in some ornithischians, pterosaurs, cetaceans, dicynodonts, anuran tadpoles, monotremes, sirens, pufferfish, billfishes and cephalopods.

The jaw is any opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term jaws is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serving to open and close it and is part of the body plan of humans and most animals.

Agkistrodon piscivorus is a species of pit viper in the subfamily Crotalinae of the family Viperidae. It is one of the world's few semiaquatic vipers, and is native to the Southeastern United States. As an adult, it is large and capable of delivering a painful and potentially fatal bite. When threatened, it may respond by coiling its body and displaying its fangs. Individuals may bite when feeling threatened or being handled in any way. It tends to be found in or near water, particularly in slow-moving and shallow lakes, streams, and marshes. It is a capable swimmer, and like several species of snakes, is known to occasionally enter bays and estuaries and swim between barrier islands and the mainland.

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae. They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million until about 11,000 years ago.

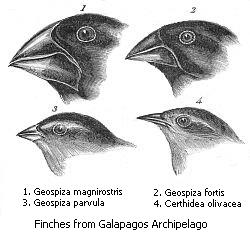

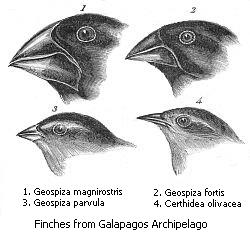

Divergent evolution or divergent selection is the accumulation of differences between closely related populations within a species, sometimes leading to speciation. Divergent evolution is typically exhibited when two populations become separated by a geographic barrier and experience different selective pressures that drive adaptations to their new environment. After many generations and continual evolution, the populations become less able to interbreed with one another. The American naturalist J. T. Gulick (1832–1923) was the first to use the term "divergent evolution", with its use becoming widespread in modern evolutionary literature. Classic examples of divergence in nature are the adaptive radiation of the finches of the Galapagos or the coloration differences in populations of a species that live in different habitats such as with pocket mice and fence lizards.

Apparent death is a behavior in which animals take on the appearance of being dead. It is an immobile state most often triggered by a predatory attack and can be found in a wide range of animals from insects and crustaceans to mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Apparent death is separate from the freezing behavior seen in some animals.

Tiliqua rugosa, most commonly known as the shingleback skink or bobtail lizard, is a short-tailed, slow-moving species of blue-tongued skink endemic to Australia. It is commonly known as the shingleback or sleepy lizard. Three of its four recognised subspecies are found in Western Australia, where the bobtail name is most frequently used. The fourth subspecies, T. rugosa asper, is the only one native to eastern Australia, where it goes by the common name of the eastern shingleback.

Agonism is a broad term which encompasses many behaviours that result from, or are triggered by biological conflict between competing organisms. Approximately 23 shark species are capable of producing such displays when threatened by intraspecific or interspecific competitors, as an evolutionary strategy to avoid unnecessary combat. The behavioural, postural, social and kinetic elements which comprise this complex, ritualized display can be easily distinguished from normal, or non-display behaviour, considered typical of that species' life history. The display itself confers pertinent information to the foe regarding the displayer's physical fitness, body size, inborn biological weaponry, confidence and determination to fight. This behaviour is advantageous because it is much less biologically taxing for an individual to display its intention to fight than the injuries it would sustain during conflict, which is why agonistic displays have been reinforced through evolutionary time, as an adaptation to personal fitness. Agonistic displays are essential to the social dynamics of many biological taxa, extending far beyond sharks.

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture or trap prey via stealth, luring or by strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey using sheer speed or endurance, ambush predators avoid fatigue by staying in concealment, waiting patiently for the prey to get near, before launching a sudden overwhelming attack that quickly incapacitates and captures the prey.

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on the outside by the lips and inside by the pharynx. In tetrapods, it contains the tongue and, except for some like birds, teeth. This cavity is also known as the buccal cavity, from the Latin bucca ("cheek").

Mobbing in animals is an antipredator adaptation in which individuals of prey species mob a predator by cooperatively attacking or harassing it, usually to protect their offspring. A simple definition of mobbing is an assemblage of individuals around a potentially dangerous predator. This is most frequently seen in birds, though it is also known to occur in many other animals such as the meerkat and some bovines. While mobbing has evolved independently in many species, it only tends to be present in those whose young are frequently preyed upon. This behavior may complement cryptic adaptations in the offspring themselves, such as camouflage and hiding. Mobbing calls may be used to summon nearby individuals to cooperate in the attack.

Agonistic behaviour is any social behaviour related to fighting. The term has broader meaning than aggressive behaviour because it includes threats, displays, retreats, placation, and conciliation. The term "agonistic behaviour" was first implemented by J.P Scott and Emil Fredericson in 1951 in their paper "The Causes of Fighting in Mice and Rats" in Physiological Zoology.Agonistic behaviour is seen in many animal species because resources including food, shelter, and mates are often limited.

Marine vertebrates are vertebrates that live in marine environments. These are the marine fish and the marine tetrapods. Vertebrates are a subphylum of chordates that have a vertebral column (backbone). The vertebral column provides the central support structure for an internal skeleton. The internal skeleton gives shape, support, and protection to the body and can provide a means of anchoring fins or limbs to the body. The vertebral column also serves to house and protect the spinal cord that lies within the column.

Cranial kinesis is the term for significant movement of skull bones relative to each other in addition to movement at the joint between the upper and lower jaw. It is usually taken to mean relative movement between the upper jaw and the braincase.

Deimatic behaviour or startle display means any pattern of bluffing behaviour in an animal that lacks strong defences, such as suddenly displaying conspicuous eyespots, to scare off or momentarily distract a predator, thus giving the prey animal an opportunity to escape. The term deimatic or dymantic originates from the Greek δειματόω (deimatóo), meaning "to frighten".

The fauna of Louisiana is characterized by the region's low swamplands, bayous, creeks, woodlands, coastal marshlands and beaches, and barrier islands covering an estimated 20,000 square miles, corresponding to 40 percent of Louisiana's total land area. Southern Louisiana contains up to fifty percent of the wetlands found in the Continental United States, and are made up of countless bayous and creeks.

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and reddish pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albinos.

In evolutionary biology, mimicry in vertebrates is mimicry by a vertebrate of some model, deceiving some other animal, the dupe. Mimicry differs from camouflage as it is meant to be seen, while animals use camouflage to remain hidden. Visual, olfactory, auditory, biochemical, and behavioral modalities of mimicry have been documented in vertebrates.