Garden, Ashes (Serbo-Croatian : Bašta, pepeo) is a 1965 novel by Yugoslav author Danilo Kiš. Garden, Ashes is based on Kiš's childhood. An English translation, by William J. Hannaher, was published in 1975 by Harcourt.

Garden, Ashes (Serbo-Croatian : Bašta, pepeo) is a 1965 novel by Yugoslav author Danilo Kiš. Garden, Ashes is based on Kiš's childhood. An English translation, by William J. Hannaher, was published in 1975 by Harcourt.

The narrative is told from the perspective of a young boy, Andi Scham, who at the beginning of the novel resides in Novi Sad in Yugoslavia. His absent father, Eduard Schamm, is an eccentric and meticulous railway inspector and a writer whose unfinished work is the third edition of a travel guide called Bus, Ship, Rail and Air Travel Guide – the updated edition, which Scham will never complete, is to be encyclopedic in its scope. After being shot at by gendarme soldiers, Eduard relocates his family to Hungary where Andi enters primary school. Later Eduard is sent to a ghetto and is then deported to Auschwitz, never to return to his family. Eduard presumably dies in the camps, though Andi insists that his father has merely disappeared.

The narrative structure becomes more fractured after Eduard's departure. Andi imagines that his father is following him in disguise and invents stories about his parents' first meeting. Andi acknowledges that "ever since my father vanished from the story, from the novel, everything has come loose, fallen apart." In the final scene of the novel, Andi wanders through the same woods that were the setting for an earlier imagined encounter in which Eduard was accused of being an Allied spy. He claims that his father's "ghost" haunts those woods. Andi's mother encourages him to leave as it is getting dark. [1]

Andi is incredibly imaginative, to a fault. He is plagued by recurring nightmares and is haunted by illusions of his father. Only toward the end of the novel, as he starts to read adventure novels, does he begin to constrain his imagination. [2]

The novel is structured as a "loosely connected chronological sequence of half-explained adventures". Most of the focus is on the father, and what happens to the mother and child, living with difficulty in impoverished circumstances, is only partially explained. Refusing to give any moral judgment of the father, Kiš portrays him as a complex character, "enigmatic and half-crazed..., a man with an eloquent tongue and a fanciful mind who frequently abandoned family, sobriety, and reason", according to Murlin Croucher. [3]

Though Andi is a child, his narratorial voice is remarkably mature. Mark Thompson describes Andi as a "hybrid narrator who blends the expressive power of an accomplished artist with the limited understanding-- but the unlimited imagination, or intuition-- of a young person." [2]

Kiš openly acknowledged that the Scham family was based on his own family. “I am convinced that it is me, that it’s my father, my mother, my sister,” Kiš said in an interview on Garden, Ashes. [4]

Eduard Scham resembles Kiš's own father (also named Eduard) in his appearance, eccentric personality, and career as a railway inspector-cum-travel guide author.

The events of the novel closely follow Kiš's actual life during World War II. Like his fictional counterpart, Eduard Kiš narrowly escaped a shooting death by gendarme officers in Novi Sad, then relocated his family to Hungary. Also like Scham, Eduard Kiš was confined to a ghetto and later sent to Auschwitz. As Andi does in the novel, Kiš himself would insist that his father had not died in the camps but had merely "disappeared." [2]

A recurring symbol in the novel is Andi's mother's Singer sewing machine. Kiš describes the machine in detail and includes a sketch of the machine, so as to convey not only that Andi's mother uses the machine to create beauty but that the machine itself is beautiful. This beauty symbolizes home or the ability to feel at home. [5] When the Schams flee to Hungary, the sewing machine is lost "in the confusion of war." [1] This loss symbolizes how the war destroys Andi's home. [5]

Upon hearing that his uncle has died, Andi begins to dwell obsessively on his own mortality. This realization can be seen as Andi's first step toward self-analysis. Andi becomes determined to outwit death by catching "the angel of sleep." Though he is not successful in this endeavor, Andi's struggle with his own mortality reveals the character's sensitive nature and makes clear that Kiš does not idolize childhood innocence. [2]

Andi is plagued with nightmares throughout the novel. Intrusive thoughts about his own mortality often keep Andi from sleeping, and when he does fall asleep he is restless and plagued by nightmares. Andi has recurring dreams of conquering the "angel of death." These dreams are so terrifying that when he wakes up his first thoughts are "akin to mortal fear." Andi only overcomes these dreams when in his dreams he declares "I AM DREAMING," which subdues the angel. He then begins to channel his "darkest impulses" into his dreams, eating the poppyseed cakes that are denied him in his real life or pursuing a village woman with whom he is fascinated. [1]

Žarko Martinović argues that Andi's nightmares are best classified as traumatic dreams. Sufferers of posttraumatic stress disorder often experience these types of dreams. Andi suppresses his nightmares by lucid dreaming. Kiš wrote Garden, Ashes long before lucid dreaming became a well-researched field of study. [6]

The novel's title possibly derives from an accusation made by the Hungarian fascists against the father: (falsely) accused of being an Allied spy, an accusation the son wants to believe since it increases his father's heroic status, he is said to direct the Allied planes to deliver the bombs that turn "everything into dust and ashes". [7] More generally, the Holocaust transforms objects of beauty ("gardens") into ashes. [5]

Kiš described Garden, Ashes as part of his “family cycle” trilogy, consisting of Early Sorrows (1970), Garden, Ashes, and The Hourglass (1972). [8] Garden, Ashes contains many scenes also present in Early Sorrows, including Andi's relationship with Julia Szabo, Eduard's departure, and the pogrom scene. [9]

Kiš wrote Garden, Ashes while employed as a lector at the University of Strasbourg. Compared to his earlier novels, Kiš found Garden, Ashes much more difficult to write. [2]

The novel "was greeted by the critics as a significant work by a promising young writer". [10] By the time it was translated and published in English, it had already appeared in French, German, Polish, and Hungarian. [3] English reviews were mixed but mostly positive. Murlin Croucher praised the "rich yet youthful and slightly hyperbolic style", though he felt that the book lacked an overall purpose. Croucher also remarked on the impossibility of distinguishing between fact and fiction, [3] which became a hallmark of Kiš's work. [11] Vasa Mihailovich comments on the novel's charm, which he says was unsurpassed even by Kiš's later "more sophisticated and mature books". [10]

Many critics have examined the novel as a work of Holocaust literature. Like other authors who were young children during the Holocaust, Kiš uses literature to confront childhood traumas. [2]

Garden, Ashes is unusual in that while it is ostensibly about the Holocaust, since Eduard dies in Auschwitz, Kiš makes few explicit references to the Holocaust. Aleksander Stević argues that Kiš chooses to have Andi suppress memories of the Holocaust so as to give Eduard autonomy. Andi imagines that his father is being persecuted for being a raving genius, rather than for being a Jew. For example, Andi describes his family's move to the suburbs following a pogrom as "guided by my father's star." Though the star in question is clearly the Star of David, Andi later refers to this star as "the star of his destiny," making the star into a symbol of his father's travels. With this choice, Kiš humanizes his father, who was stripped of his identity by the Holocaust. [12]

Garden, Ashes is often compared to Fatelessness , a 1975 semi-autobiographical novel by Hungarian author Imre Kertész. Mark Thompson describes Fatelessness as the "sequel or sibling" of Garden, Ashes. György, the protagonist of Fatelessness, bears resemblance to Andi in that his innocence blinds him to what is going on around him. György continually tries to normalize and reconcile what he has seen in the camps, as a way of coping with horrific events, much like how Andi suppresses images of the war.

Both Kertész and Kiš attempt to humanize victims of the Holocaust. When asked by reporters if the camps are as horrific as they've heard, György claims that at times he was "happy" in the camps, a form of resistance against a regime that wants to strip him of his emotional autonomy. This is similar to how in Garden, Ashes in how Andi continually portrays his father as an exceptional genius who is persecuted not for religion but for his genius.

Fatelessness and Garden, Ashes were published at a time when discussion on the Holocaust were discouraged by the Hungarian and Yugoslav governments. The novels are credited for inciting discourse on the Holocaust in these countries. [13] [2]

Imre Kertész was a Hungarian author and recipient of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Literature, "for writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history". He was the first Hungarian to win the Nobel in Literature. His works deal with themes of the Holocaust, dictatorship, and personal freedom.

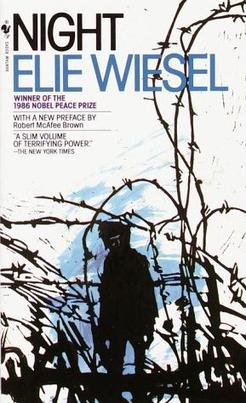

Night is a 1960 memoir by Elie Wiesel based on his Holocaust experiences with his father in the Nazi German concentration camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald in 1944–1945, toward the end of the Second World War in Europe. In just over 100 pages of sparse and fragmented narrative, Wiesel writes about his loss of faith and increasing disgust with humanity, recounting his experiences from the Nazi-established ghettos in his hometown of Sighet, Romania, to his migration through multiple concentration camps. The typical parent–child relationship is inverted as his father dwindled in the camps to a helpless state while Wiesel himself became his teenaged caregiver. His father died in January 1945, taken to the crematory after deteriorating from dysentery and a beating while Wiesel lay silently on the bunk above him for fear of being beaten too. The memoir ends shortly after the United States Army liberated Buchenwald in April 1945.

Melvin Mermelstein was a Czechoslovak-born American Holocaust survivor and autobiographer. A Jew, he was the sole survivor of his family's extermination at Auschwitz concentration camp.

György (George) Konrád was a Hungarian novelist, pundit, essayist and sociologist known as an advocate of individual freedom.

Danilo Kiš was a Yugoslav and Serbian novelist, short story writer, essayist and translator. His best known works include Hourglass, A Tomb for Boris Davidovich and The Encyclopedia of the Dead.

Fateless or Fatelessness is a novel by Imre Kertész, winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize for literature, written between 1960 and 1973 and first published in 1975.

The Holocaust has been a prominent subject of art and literature throughout the second half of the twentieth century. There is a wide range of ways–including dance, film, literature, music, and television–in which the Holocaust has been represented in the arts and popular culture.

Aleksandar Tišma. was a Serbian novelist.

This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen, also known as Ladies and Gentlemen, to the Gas Chamber, is a collection of short stories by Tadeusz Borowski, which were inspired by the author's concentration camp experience. The original title in the Polish language was Pożegnanie z Marią. Following two year imprisonment at Auschwitz, Borowski had been liberated from the Dachau concentration camp in the spring of 1945, and went on to write his collection in the following years in Stalinist Poland. The book, translated in 1959, was featured in the Penguin's series "Writers from the Other Europe" from the 1970s.

Lucille Eichengreen was a survivor of the Łódź (Litzmannstadt) Ghetto and the Nazi German concentration camps of Auschwitz, Neuengamme and Bergen-Belsen. She moved to the United States in 1946, married, had two sons and worked as an insurance agent. In 1994, she published From Ashes to Life: My Memories of the Holocaust. She frequently lectured on the Holocaust at libraries, schools and universities in the U.S. and Germany. She took part in a documentary from the University of Giessen on life in the Ghetto, for which she was awarded an honorary doctorate.

George Mantello, a businessman with various diplomatic activities, born into a Jewish family from Transylvania, helped save thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust while working for the Salvadoran consulate in Geneva, Switzerland from 1942 to 1945 under the protection of consul Castellanos Contreras, by providing them with fictive Salvadoran citizenship papers. He publicized in mid-1944 the deportation of Hungarian Jews to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp, which had great impact on rescue, rapidly led to unprecedented large-scale grass root protests by the Swiss people and church, which was a major contributing factor to Hungary's regent Miklós Horthy stopping the transports to Auschwitz.

János Kis is a Hungarian philosopher and political scientist, who served as the inaugural leader of the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) from 1990 to 1991. He is considered to be the first Leader Hungarian parliamentary opposition.

Yehiel De-Nur, also known by his pen name Ka-Tsetnik 135633, born Yehiel Feiner, was a Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor, whose books were inspired by his time as a prisoner in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Early Sorrows: For Children and Sensitive Readers is a collection of nineteen short stories by Yugoslav author Danilo Kiš.

István Farkas was a Hungarian painter, publisher and victim of the Holocaust.

Psalm 44 is a novel by Yugoslav author Danilo Kiš. The novel was written in 1960 and published in 1962, along with his novel The Attic, and tells the story of the last few hours of a woman and her child in a Nazi concentration camp, before they escape. In a narrative full of flashbacks and stream-of-consciousness passages, with elements derived from his own life, Kiš sketches the life of a Jewish woman who witnesses the Novi Sad raid, is deported to a Nazi camp where she gives birth to a boy, and escapes with the help of another woman. Months after the war's end she is reunited with her lover, a Jewish doctor who had assisted the Nazis in Joseph Mengele-style experiments.

Šid railway station is a railway station on Belgrade–Šid, first on Bijeljina–Šid railway and railway junction. Located in Šid, Serbia. Railroad continues to Tovarnik in one direction, in another direction to Kukujevci-Erdevik, and a third direction towards to Sremska Rača. Šid railway station consists of 10 railway track.

Peščanik is a 1972 novel by Yugoslav novelist Danilo Kiš, translated as Hourglass by Ralph Manheim (1990). Hourglass tells the account of the final months in a man's life before he is sent to a concentration camp. Hourglass is in part based on the life of the author's Jewish father, who was murdered in Auschwitz.

Angela Orosz-Richt is a Holocaust survivor. Of several thousand babies born at the Auschwitz complex, she is one of the few who survived to liberation. Her testimony has led to the 21st century convictions of two former Nazis.

The 2002 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Hungarian novelist Imre Kertész (1929–2016) "for writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history." He is the only Nobel Prize recipient from Hungary.