The Geisenheim Yeast Breeding Center was founded in 1894 and is located in the town of Geisenheim, in Germany's Rheingau.

The Geisenheim Yeast Breeding Center was founded in 1894 and is located in the town of Geisenheim, in Germany's Rheingau.

In 1876, Swiss-born professor Hermann Müller joined the Geisenheim Institute, where he developed his namesake grape variety Müller-Thurgau, which became Germany's most-planted grape variety in the 1970s. He was selecting yeasts for the institute's necessities. But it was Julius Wortmann on whose initiative the foundation of the renowned yeast breeding center in 1894 took place under director Rudolf Goethe. This center continued and transferred the pathbreaking studies of Louis Pasteur and Emil Christian Hansen, achieved by isolating pure yeast and the dissemination of these, of which in practice makes a significant contribution to the improvement of quality in winemaking. Institutions followed this example all over the world. [1]

Julius Wortmann succeeded Goethe as director on 1 April 1903, of the educational institution for wine, fruit, and horticulture (the official name since 1901). He held his office as director for a total of 18 years, until 1921. As director, Wortmann led the work of his predecessor and father-in-law, Rudolf Goethe. In 1905, a modern winery was founded, with a wine press house and the educational establishment acquired the Geisenheim vineyard ″Fuchsberg″ still famous today comprising 5 ha of grape stock. Under Julius Wortmann, it came also to important future-oriented changes. In the course of studies, teaching and examination contents have been adapted consequently.

In 1924, the "yeast breeding center" was integrated into the "plant physiological experimental station" of the educational and research institute for wine, fruit, vegetables, and horticulture under the direction of Prof. Dr. Karl Kroemer.

In 1932, a renaming of the "Plant Physiological Experimental Station" to the "Botanical Institute" under the direction of Prof. Dr. Hugo Schanderl took place. Essential research areas were the systematic treatment of the problematic yeasts as well as other biofilm-forming yeasts and their interactions with pure yeasts. Hugo Schanderl wrote the first book on the microbiology of must and wine.

Since 1966, Prof. Dr. Helmut Hans Dittrich has been head of the department of research on metabolic and physiological performance of microorganisms in the medium. Fermentation process and selection of yeasts with low formation SO2-binding metabolites were also in the foreground, such as studies on the origin and avoidance of microbially conditioned false aromas such as acetic acid, ester tone, buckwheat, and lactic acid note. New drying technologies simplified the application of pure yeast cultures as dry instant powder, and the breeding of cultures regained importance. [2]

A hundred years after its foundation, the "Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry" came under the direction of Prof. Dr. Manfred Großmann. His research and development work was in the areas of stress research, aroma development, and biotechnological implementation of the findings of microbial processes in juice, wine, and wine-associated production areas such as cool climates. [3] New Research fields to be added were genetically modified wine yeasts and risk accompanying research for their use as well as aroma development in wines through the use of microbial mixed cultures. The Geisenheim Yeast Finder supports practitioners in finding suitable yeast for their application. [4]

Since 2019, the center has focused on working on lager and wine yeast strain improvements in fermentation and aroma compound production and has started work on biocontrol agents, the necrotrophic mycoparasitic predator yeasts. This group of yeasts is able to kill other fungi in a process known as necrotrophic mycoparasitism. Geisenheim has started to unravel the molecular biology behind this process and look for collaborations to apply these organisms to a more sustainable agriculture.

Riesling is a white grape variety that originated in the Rhine region. Riesling is an aromatic grape variety displaying flowery, almost perfumed, aromas as well as high acidity. It is used to make dry, semi-sweet, sweet, and sparkling white wines. Riesling wines are usually varietally pure and are seldom oaked. As of 2004, Riesling was estimated to be the world's 20th most grown variety at 48,700 hectares, but in terms of importance for quality wines, it is usually included in the "top three" white wine varieties together with Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc. Riesling is a variety that is highly "terroir-expressive", meaning that the character of Riesling wines is greatly influenced by the wine's place of origin.

Botrytis cinerea is a necrotrophic fungus that affects many plant species, although its most notable hosts may be wine grapes. In viticulture, it is commonly known as "botrytis bunch rot"; in horticulture, it is usually called "grey mould" or "gray mold".

Winemaking or vinification is the production of wine, starting with the selection of the fruit, its fermentation into alcohol, and the bottling of the finished liquid. The history of wine-making stretches over millennia. The science of wine and winemaking is known as oenology. A winemaker may also be called a vintner. The growing of grapes is viticulture and there are many varieties of grapes.

Carbonic maceration is a winemaking technique, often associated with the French wine region of Beaujolais, in which whole grapes are fermented in a carbon dioxide rich environment before crushing. Conventional alcoholic fermentation involves crushing the grapes to free the juice and pulp from the skin with yeast serving to convert sugar into ethanol. Carbonic maceration ferments most of the juice while it is still inside the grape, although grapes at the bottom of the vessel are crushed by gravity and undergo conventional fermentation. The resulting wine is fruity with very low tannins. It is ready to drink quickly but lacks the structure for long-term aging. In extreme cases such as Beaujolais nouveau, the period between picking and bottling can be less than six weeks.

Red wine is a type of wine made from dark-colored grape varieties. The color of the wine can range from intense violet, typical of young wines, through to brick red for mature wines and brown for older red wines. The juice from most purple grapes is greenish-white, the red color coming from anthocyan pigments present in the skin of the grape. Much of the red wine production process involves extraction of color and flavor components from the grape skin.

White wine is a wine that is fermented without skin contact. The colour can be straw-yellow, yellow-green, or yellow-gold. It is produced by the alcoholic fermentation of the non-coloured pulp of grapes, which may have a skin of any colour. White wine has existed for at least 4,000 years.

Malolactic conversion is a process in winemaking in which tart-tasting malic acid, naturally present in grape must, is converted to softer-tasting lactic acid. Malolactic fermentation is most often performed as a secondary fermentation shortly after the end of the primary fermentation, but can sometimes run concurrently with it. The process is standard for most red wine production and common for some white grape varieties such as Chardonnay, where it can impart a "buttery" flavor from diacetyl, a byproduct of the reaction.

Maceration is the winemaking process where the phenolic materials of the grape—tannins, coloring agents (anthocyanins) and flavor compounds—are leached from the grape skins, seeds and stems into the must. To macerate is to soften by soaking, and maceration is the process by which the red wine receives its red color, since raw grape juice is clear-grayish in color. In the production of white wines, maceration is either avoided or allowed only in very limited manner in the form of a short amount of skin contact with the juice prior to pressing. This is more common in the production of varietals with less natural flavor and body structure like Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon. For Rosé, red wine grapes are allowed some maceration between the skins and must, but not to the extent of red wine production.

A wine fault is a sensory-associated (organoleptic) characteristic of a wine that is unpleasant, and may include elements of taste, smell, or appearance, elements that may arise from a "chemical or a microbial origin", where particular sensory experiences might arise from more than one wine fault. Wine faults may result from poor winemaking practices or storage conditions that lead to wine spoilage.

Hermann Müller, was a Swiss botanist, plant physiologist, oenologist and grape breeder. He called himself Müller-Thurgau, taking the name of his home canton.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to wine:

The process of fermentation in winemaking turns grape juice into an alcoholic beverage. During fermentation, yeasts transform sugars present in the juice into ethanol and carbon dioxide. In winemaking, the temperature and speed of fermentation are important considerations as well as the levels of oxygen present in the must at the start of the fermentation. The risk of stuck fermentation and the development of several wine faults can also occur during this stage, which can last anywhere from 5 to 14 days for primary fermentation and potentially another 5 to 10 days for a secondary fermentation. Fermentation may be done in stainless steel tanks, which is common with many white wines like Riesling, in an open wooden vat, inside a wine barrel and inside the wine bottle itself as in the production of many sparkling wines.

Solaris is a variety of grape used for white wine. It was created in 1975 at the grape breeding institute in Freiburg, Germany by Norbert Becker.

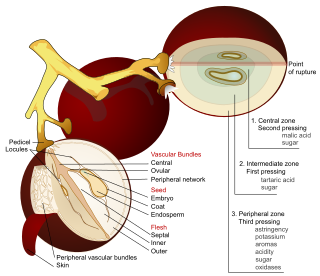

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. There is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

This glossary of winemaking terms lists some of terms and definitions involved in making wine, fruit wine, and mead.

Autolysis in winemaking relates to the complex chemical reactions that take place when a wine spends time in contact with the lees, or dead yeast cells, after fermentation. While for some wines - and all beers - autolysis is undesirable, it is a vital component in shaping the flavors and mouth feel associated with premium Champagne production. The practice of leaving a wine to age on its lees has a long history in winemaking dating back to Roman winemaking. The chemical process and details of autolysis were not originally understood scientifically, but the positive effects such as a creamy mouthfeel, breadlike and floral aromas, and reduced astringency were noticed early in the history of wine.

In winemaking, clarification and stabilization are the processes by which insoluble matter suspended in the wine is removed before bottling. This matter may include dead yeast cells (lees), bacteria, tartrates, proteins, pectins, various tannins and other phenolic compounds, as well as pieces of grape skin, pulp, stems and gums. Clarification and stabilization may involve fining, filtration, centrifugation, flotation, refrigeration, pasteurization, and/or barrel maturation and racking.

In viticulture, ripeness is the completion of the ripening process of wine grapes on the vine which signals the beginning of harvest. What exactly constitutes ripeness will vary depending on what style of wine is being produced and what the winemaker and viticulturist personally believe constitutes ripeness. Once the grapes are harvested, the physical and chemical components of the grape which will influence a wine's quality are essentially set so determining the optimal moment of ripeness for harvest may be considered the most crucial decision in winemaking.

The role of yeast in winemaking is the most important element that distinguishes wine from fruit juice. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts the sugars of the fruit into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the process of fermentation. The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early in order to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine such as with dessert wines. This can be achieved by dropping fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast are inactive, sterile filtering the wine to remove the yeast or fortification with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off the yeast cells. If fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients and the wine has not yet reached dryness, this is considered a stuck fermentation.

Ramesh Chandra Ray is an agriculture and food microbiologist, author, and editor. He is the former Principal Scientist (Microbiology), and Head of the Regional Centre at Indian Council of Agricultural Research ICAR - Central Tuber Crops Research Institute in Bhubaneswar, India.