Moses B. Stuart was an American biblical scholar.

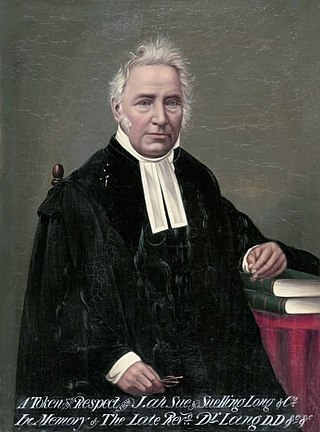

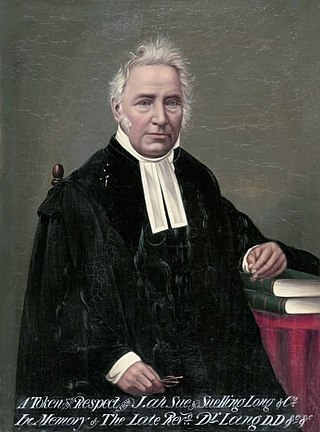

John Dunmore Lang was a Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, historian, politician and activist. He was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian republicanism.

William Ward Duffield was an executive in the coal industry, a railroad construction engineer, and an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. After the war he was appointed Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey.

The Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) was a Presbyterian denomination existing from 1789 to 1958. In that year, the PCUSA merged with the United Presbyterian Church of North America. The new church was named the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. It was a predecessor to the contemporary Presbyterian Church (USA).

James Forbes was a Scottish-Australian Presbyterian minister and educator. He founded the Melbourne Academy, later Scotch College.

William McIntyre was a Scottish-Australian Presbyterian minister and educator.

The fundamentalist–modernist controversy is a major schism that originated in the 1920s and 1930s within the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. At issue were foundational disputes about the role of Christianity; the authority of the Bible; and the death, resurrection, and atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ. Two broad factions within Protestantism emerged: fundamentalists, who insisted upon the timeless validity of each doctrine of Christian orthodoxy; and modernists, who advocated a conscious adaptation of the Christian faith in response to the new scientific discoveries and moral pressures of the age. At first, the schism was limited to Reformed churches and centered around the Princeton Theological Seminary, whose fundamentalist faculty members founded Westminster Theological Seminary when Princeton went in a liberal direction. However, it soon spread, affecting nearly every Protestant denomination in the United States. Denominations that were not initially affected, such as the Lutheran churches, eventually were embroiled in the controversy, leading to a schism in the United States.

Amos Slaymaker was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. His younger sister, Faithful, was the mother of the nineteenth-century Presbyterian minister George Duffield.

John Monteith was a United States Presbyterian minister, educator, abolitionist and a founding father of the University of Michigan, formerly known as University of Michigania or the Catholepistemiad. Monteith served as president of the university from 1817 through 1821. During his five years in Detroit, he also served as the city's first librarian, and founded the first Protestant church in Detroit and the first Presbyterian church in what is now the State of Michigan.

Hugh Brady was an American general from Pennsylvania. He served in the Northwest Indian War under General Anthony Wayne, and during the War of 1812. Following the War of 1812, Brady remained in the military, eventually rising to the rank of major general and taking command of the garrison at Detroit. He also marginally participated in the 1832 Black Hawk War. Hugh Brady died an accidental death in 1851 when he was thrown from a horse-drawn carriage.

The Old School–New School controversy was a schism of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America that took place in 1837 and lasted for over 20 years. The Old School, led by Charles Hodge of Princeton Theological Seminary, was more conservative theologically and did not support the revival movement. It called for traditional Calvinist orthodoxy as outlined in the Westminster standards.

Francis Alison (1705–1779) was a leading minister in the Synod of Philadelphia during The Old Side-New Side Controversy

Henry Martyn Duffield was a colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War, lawyer, candidate for U.S. Representative from Michigan's 1st district in 1876; brigadier general of U.S. Volunteers during the Spanish–American War, presidential elector for Michigan in 1904, and a member of the Grand Army of the Republic.

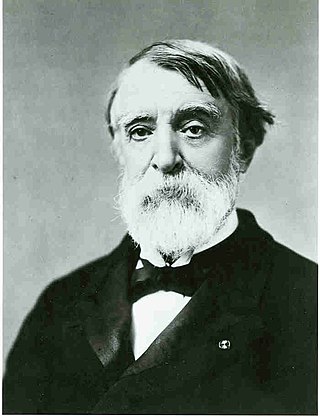

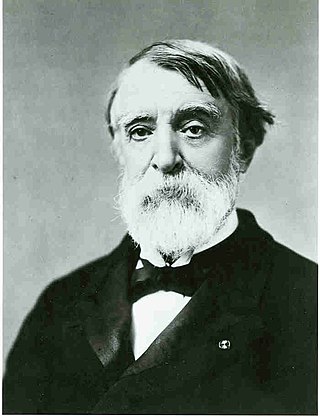

George Duffield Jr. D.D. was an American Presbyterian minister and hymnodist.

The Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland is a small, Scottish, Presbyterian church denomination. Theologically they are similar to many other Presbyterian denominations in that their office-bearers subscribe to the Westminster Confession of Faith. In practice, they are more theologically conservative than most Scottish Presbyterians and maintain a very traditional form of worship. In 1690, after the Revolution, Alexander Shields joined the Church of Scotland, and was received along with two other ministers. These had previously ministered to a group of dissenters of the United Societies at a time when unlicensed meetings were outlawed. Unlike these ministers, some Presbyterians did not join the reconstituted Church of Scotland. From these roots the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland was formed. It grew until there were congregations in several countries. In 1876 the majority of Reformed Presbyterians, or RPs, joined the Free Church of Scotland, and thus the present-day church, which remained outside this union, is a continuing church. There are currently Scottish RP congregations in Airdrie, Stranraer, Stornoway, Glasgow, and North Edinburgh. Internationally they form part of the Reformed Presbyterian Communion.

Robert Adam Holliday Lusk was a Reformed Presbyterian or Covenanter minister of the strictest sort, in a century which, according to Presbyterian historian Robert E. Thompson, was marked by increasing relaxation into less stringent manifestations of doctrine and practice amongst all branches of Presbyterianism. His career crossed paths with many prominent ministers and he was involved in numerous ecclesiastical courts at pivotal moments in the history of the Reformed Presbyterian Church. Amongst Reformed Presbyterians, he was an "Old Light," and amongst "Old Lights," he would lay claim to be an "Original Covenanter." He was descended from a long line of Scotch-Irish, and the Lusks had fled from Scotland to Ireland, escaping religious persecution; many of them settled in America prior to the American Revolutionary War.

Presbyterianism has had a presence in the United States since colonial times and has exerted an important influence over broader American religion and culture.

William Cuninghame of Lainshaw (c.1775–1849) was a Scottish landowner, known as a writer on biblical prophecy. He dated the beginning of the reign of Antichrist to 533 A.D., to coincide with a claimed date at which Justinian I gave universal rule to the Papacy, by subtracting 1260 years from the date after the French Revolution at which it was seen to turn against the Roman Catholic Church.

George Duffield was a leading eighteenth-century Presbyterian minister. He was born in Lancaster County, Province of Pennsylvania in 1732. In 1779, Duffield was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.

Nancy Jane Dean, often referred to as Jennie Dean or N. J. Dean, was an American educator and Presbyterian missionary serving Assyrian Christians in Qajar Iran. She served as the head of Fiske Seminary, a girls' boarding school in Urmia, West Azerbaijan Province.