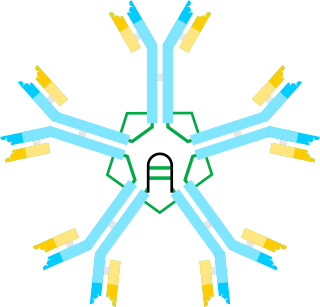

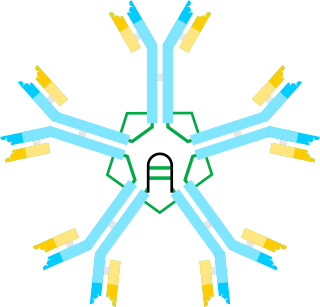

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the pathogen, called an antigen. Each tip of the "Y" of an antibody contains a paratope that is specific for one particular epitope on an antigen, allowing these two structures to bind together with precision. Using this binding mechanism, an antibody can tag a microbe or an infected cell for attack by other parts of the immune system, or can neutralize it directly.

Neural Darwinism is a biological, and more specifically Darwinian and selectionist, approach to understanding global brain function, originally proposed by American biologist, researcher and Nobel-Prize recipient Gerald Maurice Edelman. Edelman's 1987 book Neural Darwinism introduced the public to the theory of neuronal group selection (TNGS) – which is the core theory underlying Edelman's explanation of global brain function.

In biology and genetics, the germline is the population of a multicellular organism's cells that pass on their genetic material to the progeny (offspring). In other words, they are the cells that form the egg, sperm and the fertilised egg. They are usually differentiated to perform this function and segregated in a specific place away from other bodily cells.

The Weismann barrier, proposed by August Weismann, is the strict distinction between the "immortal" germ cell lineages producing gametes and "disposable" somatic cells in animals, in contrast to Charles Darwin's proposed pangenesis mechanism for inheritance. In more precise terminology, hereditary information moves only from germline cells to somatic cells. This does not refer to the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that no sequential information can travel from protein to DNA or RNA, but both hypotheses relate to a gene-centric view of life.

This list catalogs well-accepted theories in science and pre-scientific natural philosophy and natural history which have since been superseded by scientific theories. Many discarded explanations were once supported by a scientific consensus, but replaced after more empirical information became available that identified flaws and prompted new theories which better explain the available data. Pre-modern explanations originated before the scientific method, with varying degrees of empirical support.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is one of several isotypes of antibody that are produced by vertebrates. IgM is the largest antibody, and it is the first antibody to appear in the response to initial exposure to an antigen. In humans and other mammals that have been studied, plasmablasts residing in the spleen are the main source for specific IgM production.

César Milstein, CH, FRS was an Argentinian-born British biochemist in the field of antibody research. Milstein shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984 with Niels Kaj Jerne and Georges J. F. Köhler for developing the hybridoma technique for the production of monoclonal antibodies.

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies found in vertebrates.

V(D)J recombination is the mechanism of somatic recombination that occurs only in developing lymphocytes during the early stages of T and B cell maturation. It results in the highly diverse repertoire of antibodies/immunoglobulins and T cell receptors (TCRs) found in B cells and T cells, respectively. The process is a defining feature of the adaptive immune system.

Immunoglobulin class switching, also known as isotype switching, isotypic commutation or class-switch recombination (CSR), is a biological mechanism that changes a B cell's production of immunoglobulin from one type to another, such as from the isotype IgM to the isotype IgG. During this process, the constant-region portion of the antibody heavy chain is changed, but the variable region of the heavy chain stays the same. Since the variable region does not change, class switching does not affect antigen specificity. Instead, the antibody retains affinity for the same antigens, but can interact with different effector molecules.

The word allotype comes from two Greek roots, allo meaning 'other or differing from the norm' and typos meaning 'mark'. In immunology, allotype is an immunoglobulin variation that can be found among antibody classes and is manifested by heterogeneity of immunoglobulins present in a single vertebrate species. The structure of immunoglobulin polypeptide chain is dictated and controlled by number of genes encoded in the germ line. However, these genes, as it was discovered by serologic and chemical methods, could be highly polymorphic. This polymorphism is subsequently projected to the overall amino acid structure of antibody chains. Polymorphic epitopes can be present on immunoglobulin constant regions on both heavy and light chains, differing between individuals or ethnic groups and in some cases may pose as immunogenic determinants. Exposure of individuals to a non-self allotype might elicit an anti- allotype response and became cause of problems for example in a patient after transfusion of blood or in a pregnant woman. However, it is important to mention that not all variations in immunoglobulin amino acid sequence pose as a determinant responsible for immune response. Some of these allotypic determinants may be present at places that are not well exposed and therefore can be hardly serologically discriminated. In other cases, variation in one isotype can be compensated by the presence of this determinant on another antibody isotype in one individual. This means that divergent allotype of heavy chain of IgG antibody may be balanced by presence of this allotype on heavy chain of for example IgA antibody and therefore is called isoallotypic variant. Especially large number of polymorphisms were discovered in IgG antibody subclasses. Which were practically used in forensic medicine and in paternity testing, before replaced by modern day DNA fingerprinting.

Immunoglobulin heavy locus, also known as IGH, is a region on human chromosome 14 that contains a gene for the heavy chains of human antibodies.

Immunoglobulin lambda locus, also known as IGL@, is a region on the q arm of human chromosome 22, region 11.22 (22q11.22) that contains genes for the lambda light chains of antibodies.

Ig heavy chain V-III region VH26 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the IGHV@ gene.

In evolutionary developmental biology, the concept of deep homology is used to describe cases where growth and differentiation processes are governed by genetic mechanisms that are homologous and deeply conserved across a wide range of species.

Somatic hypermutation is a cellular mechanism by which the immune system adapts to the new foreign elements that confront it, as seen during class switching. A major component of the process of affinity maturation, SHM diversifies B cell receptors used to recognize foreign elements (antigens) and allows the immune system to adapt its response to new threats during the lifetime of an organism. Somatic hypermutation involves a programmed process of mutation affecting the variable regions of immunoglobulin genes. Unlike germline mutation, SHM affects only an organism's individual immune cells, and the mutations are not transmitted to the organism's offspring. Because this mechanism is merely selective and not precisely targeted, somatic hypermutation has been strongly implicated in the development of B-cell lymphomas and many other cancers.

Antibody structure is made up of two heavy-chains and two light-chains. These chains are held together by disulfide bonds. The arrangement or processes that put together different parts of this antibody molecule play important role in antibody diversity and production of different subclasses or classes of antibodies. The organization and processes take place during the development and differentiation of B cells. That is, the controlled gene expression during transcription and translation coupled with the rearrangements of immunoglobulin gene segments result in the generation of antibody repertoire during development and maturation of B cells.

The genome of most cells of eukaryotes remains mainly constant during life. However, there are cases of genome being altered in specific cells or in different life cycle stages during development. For example, not every human cell has the same genetic content as red blood cells which are devoid of nucleus. One of the best known groups in respect of changes in somatic genome are ciliates. The process resulting in a variation of somatic genome that differs from germline genome is called somatic genome processing.

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of evolution and the relatedness of different groups of living things. The alternatives in question do not deny that evolutionary changes over time are the origin of the diversity of life, nor that the organisms alive today share a common ancestor from the distant past ; rather, they propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change over time, arguing against mutations acted on by natural selection as the most important driver of evolutionary change.

A somatic mutation is a change in the DNA sequence of a somatic cell of a multicellular organism with dedicated reproductive cells; that is, any mutation that occurs in a cell other than a gamete, germ cell, or gametocyte. Unlike germline mutations, which can be passed on to the descendants of an organism, somatic mutations are not usually transmitted to descendants. This distinction is blurred in plants, which lack a dedicated germline, and in those animals that can reproduce asexually through mechanisms such as budding, as in members of the cnidarian genus Hydra.